Back to selection

Back to selection

Courage of Conviction: A Conversation with Ida Director Pawel Pawlikowski

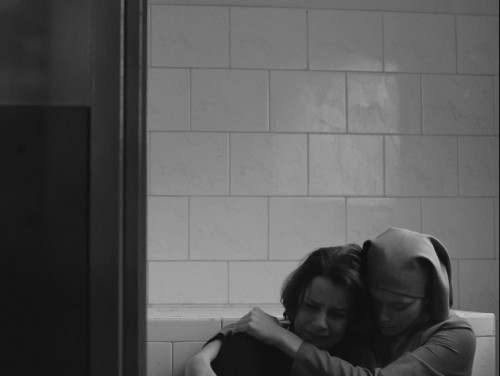

Ida

Ida Although state-side cinephiles may not be familiar with the work of filmmaker Pawel Pawlikowski or the nuances of Polish history, here at Filmmaker Magazine we suspect you’re about to find both deeply compelling. In Ida, a beautifully wrought gem of a film, the writer/director brings audiences the story of Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska), a young orphan raised by Polish Catholic nuns who meets her next of kin — the hard-drinking and cynical Wanda (Agata Kulesz) — on the eve of joining the convent, and learns that her family is Jewish. Together, the women set off on a road trip seeking the truth about their family’s past. In this conversation, Pawlikowski discusses his relationship to religion, intentionally axing his most beautiful images, and why Ida includes only two moving shots — the final two.

Filmmaker: What brought you to Ida?

Pawlikowski: I started the project [by setting it] in 1962 but couldn’t get it right. As soon as you start writing, you get off on the wrong foot: you start being very narrative and plot-y, trying to explain the historical situation, which is never conducive to good cinema. I stepped away and then came back to it.

But the theme has haunted me for years: what does it mean to be Christian? Can you be a good Christian without being Polish Catholic? Is religion a tribal demarcation or is it something spiritual within you? In central and Eastern Europe, religion tends to be a tribal marking of some kind, which is deeply un-Christian. If anything, Christ’s teachings are fantastically universal. What defines identity? The blood that you have? The faith you grew up with or your self-understanding? Can you escape all of these definitions and live a purely spiritual existence? Poland is full of these questions.

Then the two characters cropped up. One was the nun who discovers as an adult that she was not born into a Catholic family. Originally, there was such a priest; someone who, late on in his career, discovered that he was actually Jewish, and that changed him. It didn’t make him lose his faith, but it deepened his faith somehow. He embraced both his identities. That stayed with me.

There was also the story of Wanda, a lady I met in Oxford some time ago who seemed to me to have been two different people at different points in her life. Finally, there was the landscape: the Poland of the early ’60s, which I remember very fondly.

Filmmaker: Did religion play a big part in your childhood?

Pawlikowski: No, not at all. Neither of my parents were particularly religious. Christmas and Easter we spent with my mom’s family, with whom I’m still very close. That was more tradition — ritual — than anything else. I would go to church occasionally, but not with great conviction, when I was a kid. My father’s family had disappeared — and I never wondered why. In other words, he was half-Jewish.

Later, I rediscovered religion for myself, strangely, when I was living abroad and met a very wise Dominican priest. I’m not deeply religious, but I’m definitely part of that electro-magnetic field. It’s something that helps me define myself a little, not in terms of identity… but, well, let’s just say that Christ’s teachings are not irrelevant.

I’m now really interested in my father’s background, although growing up, he didn’t make anything of it or talk about it. He wanted to transcend all the different “identities.” I don’t know about his father, but his mother was Jewish. I discovered at some point that she had died in Auschwitz.

My father was a secular man. His mother was a doctor. They were part of a totally assimilated urban Jewish intelligentsia. There were the millions of other Jewish people who didn’t speak Polish and lived a parallel existence in shtetls. But there was also a very sizable Jewish population that was part of the bloodstream of Polish society: poets, filmmakers and the cultural elite.

Filmmaker: Class seemed more important than religion?

Pawlikowski: Class, education, and also what you subscribed to. In 1919, some people accepted the Polish state as a good thing. Others lived this separate life and didn’t mind being part of the Russian Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, or Poland — and they didn’t learn Polish. Those were two different attitudes; it’s complicated territory.

My father came from a very assimilated milieu where religion wasn’t a big deal. But when he discovered his mother died in Auschwitz, that set a certain… he had had interesting adventures during the war, but I wasn’t terribly interested in my parents. I didn’t find them cool until they died! [laughter] Now, I think, “Oh, they’re such fascinating characters. Their backgrounds are so interesting, their family histories.”

And at some point in life, usually when it’s too late, you start inquiring. First you think, “Who cares about roots? It’s not a big deal. I can transcend roots and culture.” But then, at a later point in life you think, “God, what else is there?” There are your projects, your films and books, your forward momentum, the new family you create or the projects. But at some point, you start to look back,and that’s what happened with this film.

I’m in my 50s now. I don’t see filmmaking as a career, in that I’ve never tried to “graduate” to big commercial movies. I always just made films about what interested me at the time — for better and worse, because sometimes that really didn’t interest anybody else! My last film, The Woman in the Fifth [2011, with Ethan Hawke and Kristin Scott Thomas], which I like a lot, reflects exactly where I was when I made it. I think it’s my probably most interesting feature film. Not that it’s the most popular, it’s a shot in the dark. A really intuitive and counter-intuitive film. Critics saw it as a misshapen genre film, but I didn’t intend to be genre at all, it went on its own bizarre trip. But it didn’t carry crowds with it, so fair enough. Cinema is too expensive to indulge yourself to that degree.

Filmmaker: How did you begin filmmaking?

Pawel Pawlikowski: I was originally a student of literature and philosophy in London. That’s where I started. I was also a keen photographer and I wrote stories. Poetry was what excited me most when I was in my late teens and early 20s. I loved going to films, but filmmaking didn’t seem like something I could do. The way films were made was very mysterious. I couldn’t imagine what it took to make one.

Eventually I learned by trial and error. I started making documentaries. That was a great way to learn because they weren’t “real” documentaries. I was always slightly contriving things, shaping things, being a little bit metaphorical with the truth. [laughter] Although mine weren’t classical documentaries, I think they’re by far the most interesting things I’ve ever done, but by far. After I’ve made a feature film, I can’t watch it. But one day, if someone digs them out, I wouldn’t mind seeing those documentaries again and again.

At the time, you could get money from television for documentaries that didn’t have any particular formula. You could freewheel. In 1995, that all changed and I stopped. Now that I teach, I realize that while it lasted, that was a blessing.

Filmmaker: Where do you teach?

Pawel Pawlikowski: I taught a lot at the National Film School in England. Now I teach at the Andrzej Wajda Warsaw Film School in Poland. When I’m not making a film, I spend time teaching. I supervise student projects from inception to final cut. If there are six film students one year, three work with me and three with the other tutor. The students choose the tutor who’s right for them; that way, they want the kind of input I can give. I act as their guide.

The Wajda Film School is a one-year, project-based program where the students aren’t required to have any film experience. They simply must be interesting artists in their own right with a really good, original project. In a way, it’s more exciting that way: they could be visual artists or novelists who have a project with strong potential.

Filmmaker: Did you know early on that you were going to shoot Ida in black-and-white and with a 1.37 aspect ratio? I love the way that in much of the film, the characters are framed so that they often only occupy the bottom half or even third of the screen. Lukasz Zal, the cinematographer, did a superb job.

Pawlikowski: Definitely black-and-white; the aspect ratio came later. My English producer was a little bit shell-shocked when I told him we’d shoot in that way. He said, “Why make it some student film? You’re better than that.” “It’s right for this story. It’s right for the image I have of that time. It’ll come to life. Don’t worry, it’ll be fine.”

That was pretty early on. Then, when I was doing tests with different lenses shooting with the actresses in their outfits, I wanted to frame it so that their bodies wouldn’t dominate in the wide shots. I had this idea to tilt the camera up. See a bit more of the air above their heads. It felt very good. They looked a bit lost in space. It felt expressive, interesting. So we started shooting like that, and then we couldn’t stop. Every now and again you see these strange shots where everything happens at the bottom of the frame, which was all great until the question of subtitling reared its ugly head! [laughter]

Filmmaker: There’s a section of the film where the subtitles appear in the middle of the frame instead of at the bottom, where the figures are positioned.

Filmmaker: There’s a section of the film where the subtitles appear in the middle of the frame instead of at the bottom, where the figures are positioned.

Pawlikowski: Yes, because if we put them where they usually go, then we wouldn’t see the actresses’ faces or eyes! But in terms of the framing, you can suggest a lot by what you limit. This framing also boxes in these characters quite interestingly, which — now that the film is done and I’m rationalizing the decision — feels relevant to this story. Only the last two shots in the film are moving shots. The penultimate one is a tracking shot — the only tracking shot in the film — and the last one is a handheld shot, which has something to do with the character’s new energy.

After the first day of filming, I lost my director of photography, Ryszard Lenczewski. He felt unwell and decided not to continue. I have worked with him many times so it was a bit like losing my right hand! I ran around in the night to my other DP friends and nobody was available, so we went with a camera operator, this young guy who had never DP’d a film before in his life.

Lucasz is a good guy. Although the fetishizing of DPs is a little bit over the top because in good films, where the image doesn’t just do beautiful things but is part of the four legs that keep the table up, framing is a work of the director and the DP together. It’s not like the DP goes off and does stuff alone. You hear that so much: “It’s a beautiful shot.” It can be a complete damning compliment, as though the photography were a separate issue from the directing. The framing was me, he lit. It was a really good collaboration. Keep calm, that was the nature of the film. In fact, we cut out the most spectacular shots. Whenever a shot looked self-consciously beautiful or contrived, it didn’t survive the cut.

Filmmaker: One of the shots that struck me shows a quiet country road, very still, until suddenly, a team of horses tows the characters’ car onto the road. The image is stunning, humorous, and surreal; it’s also gently metaphorical for their larger journey, and moves the narrative forward in a practical sense.

Pawlikowski: During my research, I saw a photograph of a police car towing a car, more or less from that angle. That was the inspiration for that shot.

Filmmaker: For our readers who are aspiring filmmakers, can you explain how you directed your actresses? For example, the subtlety of Wanda’s face when she finally really looks at her niece, for the first time we might realize that she approves of her, just a little bit.

Pawlikowski: When Wanda looks through the window at her niece standing at the bus stop? She kind of recognizes her sister in her niece, probably. God, she’s a great performer. Well, I needed that moment, so I had written it like that, and —

Filmmaker: What did your script say? Also, I believe this is the first time you’ve done a film in Polish?

Pawlikowski: “Wanda looks to the glass door and looks at her niece, takes her in and suddenly thaws.” I probably used the word “thaw” in Polish. First I wrote the script with my co-writer, Rebecca Lenkiewicz, in English. Then I re-wrote it in Polish and changed quite a bit. Polish is my first language. I speak it better than English.

When it came time to work with Agata Kulesza on that moment, we did maybe five takes of that with different gradations of warmth. And then on one something very magical happens, so that’s the one you choose. But that was a brilliant actress who gave me a lot. She was really, really good. She’s got all sorts of possibilities and intensities, and enjoys that lightly exploratory directing. We rehearse, we talk, and then when the camera rolls I can still say, “Just a tiny bit of this, a tiny bit of that, and could you not frown?” Less, less of this, more of that. It was like seasoning a soup.

Filmmaker: You spoke to her while she was acting on camera?

Pawlikowski: In some shots, yes, or before a take. When it’s a kind of an emotional dynamic moment, you can’t talk it through. But once you have a really close rapport, then you can do a lot of tricks and they trust you. But she’s a great actress who constantly adds and helps and has ideas. She’s not trying to make herself look better, she’s totally inside what the film needs. That’s a total luxury. And she was acting opposite a young woman who had never acted in her life, so that was an interesting challenge, and she was very helpful.

Filmmaker: Their difference in experience is appropriate to their characters.

Pawlikowski: It was appropriate, and she did really well. She was driving the scenes, Wanda. But she didn’t overwhelm Agata Trzebuchowska. She was always kind of giving a little space and it was very good.

Filmmaker: It’s such a coincidence that your two lead actresses have the same first name.

Pawlikowski: I know! It’s very peculiar. On the set, we called them Little Agata and Big Agata, although that sounded a bit horrible! [laughter] In Poland and Eastern Europe, people will read into Wanda’s character’s past differently; they’ll pick up on more. Before arriving in the film, her character went through a lot. A lot of things collapsed around her.

Filmmaker: If a viewer is unfamiliar with Polish history, how would you suggest that they educate themselves?

Pawlikowski: Well, nobody is going to go and read books as a result of the film, so…

Filmmaker: I might. [laughter]

Pawlikowski: There are a lot of history books about Poland during that period. The early 1960s were a time when Western ideas and culture seeped in — there was a huge explosion of jazz and fun life, a little bit of joie de vivre came back after this post-war austerity, and the sheer terror of the Stalinist period. That’s the moment I tried to convey: it’s sort of gray and a little bit oppressive, but also there’s pop music, there’s jazz, there’s a little bit of dancing and jiving.

That’s a period I was born into so it’s a defining period for me. I was born in ’57, so I was about five when it happened. But at five you take in the music, how your parents behave, how they dress. I also have a lot of family albums from that period. And I do still love that music.

Filmmaker: Are your photographs like the photographs that Wanda shows her niece in the film?

Pawlikowski: Yes, but her albums are less well-kept. Wanda just put it all under her bed in a box and she really didn’t want to be reminded. She was hoping that would never happen.

Filmmaker: When you said no one’s going to read a book on Polish history, what book did you had in mind that they should read, if so inclined?

Pawlikowski: There was a great history of Poland by Norman Davis [God’s Playground: A History of Poland, 1795-the Present], the second volume of which deals with the modern period. That’s a great read. There are also a lot of books from that period, biographies of of Communist leaders. There’s one of a Minister of the Interior. There’s one of Jakub Berman, who’s quite a notorious figure, or Julia Brystiger. Sinister but fascinating characters.

There’s also a lot of good literature, especially fiction from around that time. There was a great writer called Leopold Tyrmand; there was Marek Hlasko. There’s a real kind of flowering of culture. It was kind of inspired by Ernest Hemingway here and there, but a Polish version of it. It was a little real cool culture at the time — and jazz music was fantastic! There are some great composers and musicians from that time.

Filmmaker: In the film’s press notes, you mentioned the musicians Krzysztof Komeda, Zbigniew Namyslowski, Tomasz Stanko, Jan Ptaszyn Wroblewski. I’m going to have to go track them down.

Pawlikowski: Yeah, check them out. Komeda you probably know because he did music later for Roman Polanski’s films, Rosemary’s Baby and so on. But he was a superb composer and had a wonderful jazz group in 1960 or even earlier. At the time, Poland was practically the most liberal country in Eastern Europe. They used to say, it was the jolliest barrack in the Communist camp! (Laughter)

Filmmaker: If Ida is the first of your films that people see, how do you recommend that they explore your past work? Should they watch narratives, or documentaries, or should go chronologically?

Pawlikowski: I think chronologically would be my favorite way. I only did films about stuff that interested me at the time, and the documentaries are my favorite; especially my early documentaries such as Moscow Pietushki [1990, aka From Moscow to Pietuski, about Russian writer Benedict Yerofeyev], Dostoevsky’s Travels [1991], Serbian Epics [1992, a film that documents Bosnia during wartime]. They’re all available to watch on my website, by the way.

They’re adventures, slightly off-key. There’s something I like about them. I mean, they’re not great works of art, definitely not. But they are very lively and they deal with period, characters and situations in a very free way. Last Resort [2000, with Paddy Considine and Dina Korzun was a kind of interesting, a very low-budget film that meant a lot to me. My Summer of Love [2004, with Natalie Press and Emily Blunt], people kind of know. Women in the Fifth is a weird one, but I like it.

Filmmaker: I have a sneaking suspicion that after seeing Ida, a lot of people are going to be seeking out your past work.

Pawlikowski: Really? Well, that’d be good. I’d be happy, yeah.

Images courtesy of Music Box Films. Special thanks to Laura Kim.