Back to selection

Back to selection

“The Only Thing I Ever Really Look at in Movies is the Actors”: Paul Thomas Anderson on Inherent Vice

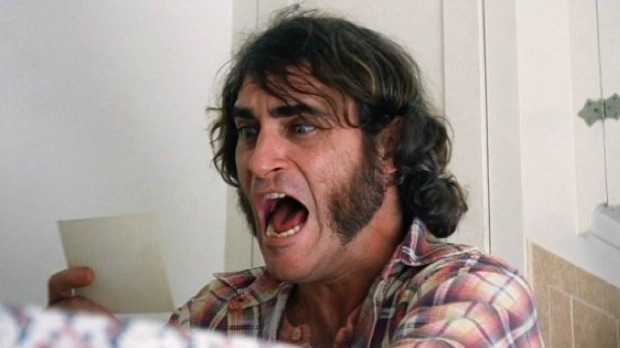

Joaquin Phoenix in Inherent Vice

Joaquin Phoenix in Inherent Vice How do you interview the filmmaker whose work has meant more to you than any others’? Paul Thomas Anderson is, for me, the best and most important director of his generation, the only person I know of who not only invites but actually earns comparison with Martin Scorsese. Like Scorsese, Anderson is a voracious film scholar whose movies both honor traditions and shatter them; also like Scorsese, he’s a committed chronicler of 20th-century American history whose perspective is consistently deeper, broader, and more original than just about anyone else’s. He’s also the best director of actors since Elia Kazan – I defy you to find any working director, anywhere, who has shepherded more extraordinary performances to the screen – and one of the most innovative filmmakers on the planet when it comes to both source music and score. There’s no pleasure the movies can give us with which he is not familiar, and which he has not provided at one time or another – he veers from art house experimentation to old-fashioned melodrama and from profound philosophical inquiry to kinetic violence and dirty sex. Plenty of other directors make great movies, but no one makes movies that have more of what makes movies great in them.

Inherent Vice is a case in point. Adapted from Thomas Pynchon’s 2009 novel, it’s a detective story that’s both a parody of mysteries and a case study in why they hit us on such a deep, primal level. Set in southern California as the ’60s are giving way to the ’70s, it tells the story of Doc Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix), a hippie private eye drawn into an increasingly convoluted missing person case by his ex-girlfriend. Doc’s investigation takes him (and the audience) through a swiftly transforming America where rampant consumerism is altering everything from sex and drugs to psychiatry and law enforcement. Doc’s sometime partner, sometime enemy, and sometime confidante Bigfoot Bjornsen (Josh Brolin) is his physical and philosophical opposite – a buzz-cut adorned, right-leaning cop who represents the establishment that the shaggy, open-minded Doc rebels against. Yet both men are saddened in their own ways by where their lives and their country are going, something they have in common with many other characters in the film. The characters who aren’t melancholy, like Martin Short’s cocaine-addled dentist Dr. Blatnoyd or Martin Donovan’s slick, cold attorney Crocker Fenway, are either whacked out of their minds or so lacking in conscience that they can’t be bothered to be bothered. The only way not to be sad about where America has gone, Anderson and Pynchon seem to be saying, is to be either crazy or evil.

With its portrait of people across the economic and political spectrum desperately chasing ideals that are already slipping through their fingers, Inherent Vice serves as a worthy companion piece to Boogie Nights, Anderson’s earlier masterpiece about lovely, foolish dreamers in an epoch of transition. No one in the history of cinema has ever handled ensembles better than Anderson, and it’s thrilling to see him painting on a sprawling Boogie Nights/Magnolia-esque canvas again. Inherent Vice can also be appreciated as the third film in a trilogy that began with There Will Be Blood and The Master, films wrestling with questions of American identity and politics and the intersection between grand forces of history and intimate human foibles and idiosyncrasies. It’s a film that sums up and contains everything that makes Anderson great, yet it’s also something completely new – I’ve never seen this precise blend of tones and styles in any other Anderson movie. I’ve never seen this blend of tones and styles in any other movie, period. I sat down with Anderson on the eve of the film’s release to talk with him about technical choices, actors, and the heartbreak of not being recognized by Elaine May.

Filmmaker: At this point the majority of your movies are period pieces, and, with the exception of Boogie Nights, they all take place before you were born, or at least before you were really conscious of what was going on around you. How do you form your ideas about how a specific era is supposed to look and feel? Do they come from other movies, or photographs, or your own imagination, or does the look grow out of the research?

Anderson: It’s all of the above. There Will Be Blood almost felt like a science fiction movie because I didn’t know anybody who was alive at the time – for something like that you’re counting on photographs to guide your way. Inherent Vice is the near past, so many of the people on the crew were alive. You’re always trying to make it real and authentic, whether you’re referencing images from the period or your own imagination, or in this case the book – not that there were a lot of descriptions in the novel of the interiors. But sometimes what happens is you get something that’s very authentic and honest to the period but it just doesn’t fit – especially in this era, when there’s such a lack of taste. Something can be right but so outrageous that it’s distracting, and you have to monitor that – if it’s accurate but it looks like you’re trying too hard, you have to find another way. The thing is, you always go into a movie with strong design ideas in mind and then they always fade away and you end up going with the thing that’s simple. Simple always seems to work out well.

Filmmaker: Aside from things like the costumes and production design, I felt like you and your cinematographer made a lot of choices involving lenses and film stock and things like that that really helped evoke the period.

Anderson: There are never-ending conversations that go on about those things. They never, ever, ever end! In this case, I was using a lot of lenses I had used on the 35mm portions of The Master. One lens that we used is a lens from 1910 or 1911 that we put a modern housing on. It’s from an old Pathé camera that we first used on Magnolia. We kept this lens with us and used it on There Will Be Blood. I love it so much I tend to overuse it, though Robert [Elswit, the cinematographer on all of Anderson’s features aside from The Master] doesn’t like it as much. We had a set of lenses that we used on The Master that I was familiar with that I thought would work really well, because I had gotten to know them – I know the imperfections, that one lens is a little cooler or one drops off a little here or one is softer.

Robert and I talked about making the film feel like a faded postcard; you want it to look like a movie from 1970, but you don’t want it to feel like a pastiche. I had a bunch of film in my garage that was improperly stored – it was 10 or 15 years old – and we shot some tests with it, and one of two things would always happen. Either it inspired us, because the blacks were very milky and the colors were a bit faded in a great way, or it was damaged beyond repair and you got no exposure at all. We wanted to use it but you couldn’t really depend on it at the risk of not getting anything, so we would use it here and there and a couple of the shots made it into the movie. More importantly, it served as a kind of inspiration for us to say, “This looks great, how can we use our modern film stocks and lenses to try to replicate that kind of look?”

Filmmaker: I want to ask a little bit about how your style has evolved. Your early movies were strongly characterized by that ‘Scope aspect ratio you favored, with a very graphic use of the wide frame. On your last couple movies you’ve gone 1.85 and narrowed the canvas a little. What factors determine your choice of aspect ratio?

Anderson: On The Master it was just a gut thing, I saw it that way in my head. I was actually seeing it in 1.66, an even boxier, more European aspect ratio. It probably has to do with the fact that most of the movies I watch are 1.33, they’re older movies. On The Master, somehow it felt more accurate to the period. And then I just kind of got into it. You know, we were watching these Robert Downey Sr. movies last night, and those were either 1.33 or 1.66, and I love the way those look. There are advantages either way, and you just kind of pick which weapon seems to fit. For Inherent Vice, I was kind of obsessed with the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers comics, and those panels are more of a box. If it had been ‘Scope it would have been the wrong feeling for this. Too big.

Filmmaker: It’s interesting that you bring up watching older films, because although a lot of people talk about ’70s films like The Long Goodbye and Night Moves in relation to Inherent Vice, for me it owes more to the classical studio movies of the ’30s and ’40s. Like those films it’s very dialogue driven, which is something I love, but I’m wondering if it’s a challenge as a director to strike the right balance between keeping the movie from becoming visually static without getting in the way of the performances and the writing.

Anderson: The only thing I ever really look at in movies is the actors. Obviously there are great movies with great production design and that kind of stuff, but… it probably comes from my first movie, where I realized early on that I didn’t have any money and I was telling a small story, but what I did have was these great actors, which ended up being the most important thing you could have. I remember talking with Jack Fisk on There Will Be Blood about needing money to do special effects, and he said, “We’ve got the best special effect there is, we’ve got Daniel Day Lewis!” And he was right. A nice two-shot with two actors performing great dialogue, that’s a staple of the movies of the ’30s that I love the most.

I don’t fetishize ’70s movies the way some people do. I love them, but my models are those ’30s films, and I’m always trying to emulate that. Sometimes you can’t – sometimes you try to get things in one shot and you realize you’re forcing the staging, and you have to own up to the fact that it’s not working. You always have to keep an eye on it to make sure that your visual ideas aren’t affectations, and that you’re not just adhering to some kind of dogma. But when you can make that kind of thing work naturally, it’s just the best.

Filmmaker: There are a lot of dialogue scenes in Inherent Vice that you let play out with minimal cuts. It reminded me of what Preston Sturges did in that shot in The Lady Eve where Henry Fonda and Barbara Stanwyck flirt for something like four or five minutes without a cut. When you shoot something like that, are you getting the more conventional coverage to play it safe, or do you just know you have it in the two-shot and leave it at that?

Anderson: It depends. Sometimes, just in case, I’ll get that coverage, or I’ll shoot it in case we need something to get into the scene before we let it play out, but most of the time you can just kind of feel that it works best playing in one. Look, cuts are great, and they’re exclusive to movies, but when you have a lot of dialogue with ping-ponging back and forth, staying out of the way is always preferable.

Filmmaker: Another thing Inherent Vice has in common with those ’30s movies is a real attention to detail in terms of the supporting cast. People who come on screen for just a couple of scenes are really well cast and beautifully defined. You’ve got a lot of stars here, but then there are also people like Hong Chau and Sasha Pieterse and Katherine Waterston and Joanna Newsom who haven’t done a ton of movies – and they’re all absolutely fantastic. Tell me a little about how you cast, and how you strike that balance between huge, known stars and newcomers.

Anderson: Believe me, it did not escape me that this was an opportunity to hire a bunch of great people. You have to be careful, because you can get into this Towering Inferno thing where every part is a big actor, but a big appeal of doing the movie for me — and this is kind of a Pynchon staple — is that the book offered the opportunity for so many great supporting parts. Everything in the book was juicy, even if it was just a couple of lines. So you have to figure out where it’s helpful to have someone like Benicio del Toro come in and deliver some information, and where it’s a great opportunity to bring in someone new.

I didn’t know Sasha’s work on Pretty Little Liars, she just came in through the usual channels through the casting director I work with. For the part of Jade, there were something like ten great actresses I had never heard of, because young Asian actresses just don’t get the opportunities that they should. But Hong was clearly the best – she might have been nervous, but it didn’t show. Then you have someone like Michelle Sinclair, who as an adult film star goes by the name Belladonna – she’s just so easy on the eyes that I felt like she fit the description of that character in the book perfectly – and Jefferson Mays, who’s a great theater actor.

So you have all those people, who maybe haven’t been in as many movies, but it’s also helpful to an audience to have very recognizable faces because there’s so much information and so much crazy shit going on. They can take it in a little easier if they’re watching someone they recognize, or someone they associate with a certain type. At the end of the day it’s just about who’s good and who’s right though, because you can cast stars in roles they’re not appropriate for and it’s not fair to anybody.

Filmmaker: I was excited to see Jeannie Berlin pop up in the movie, and it made me wonder if The Heartbreak Kid was an important film for you, or if you’re an Elaine May fan.

Anderson: I love Elaine May. I love Elaine May deeply, with passion! The Heartbreak Kid was less important to me than other Elaine May movies like Mikey & Nicky and Ishtar, or even The Birdcage, which she wrote. Where she was really important for me was in the stuff she did with Mike Nichols – those albums are like bibles around my house, I listen to them all the time. I really cast Jeannie because of how much I loved her in Margaret; she’s so delicious in that. It was funny, I met Elaine May at the New York Film Festival because she came with Jeannie Berlin, and my heart got broken when I was introduced to her and she looked at me and said “Who are you?” I wanted to crawl under a rock!

Filmmaker: I want to shift gears and ask about the music. When you have a piece that’s using a lot of source music, like this or Boogie Nights, where do you start in terms of choosing songs? Do you just start pulling records off of your shelf and seeing what hits you, or do you have to research the music of the era, or what?

Anderson: The book had a lot of great references to music, but I secretly had my own kind of stash that I really loved. That said, I would never have been aware of the Marketts song “Here Come the Ho-Dads” if it wasn’t for the book. I’m a Neil Young freak, so there’s that. It seemed like a good opportunity to use his stuff. Can is also something I love, and it’s been used in movies here and there, but I thought that track had such great energy and paranoia that it would be a great starter. It’s kind of impossible for me to look back and trace where things came from though, with that revolving door of iTunes and plucking things out of my memory, or not having any good ideas and getting lucky and hearing the right song on the radio. You have to trust that the movie gods will feed the right thing to you in some way. You never really know how things are going to fit until you place them in there, and it’s always interesting to see how they can slide into another scene or maybe begin a little earlier. That’s the most enjoyable time in editing, placing that music and seeing where it takes you.

Filmmaker: Did the movie evolve a lot during editing? I would imagine it would be tough to figure out how much or how little information to give an audience, where to place voiceover narration, etc.

Anderson: It changed less in editing than you would think, because there was so much rewriting going on while we were shooting – and we were editing more as we were shooting than we ever have before, because the piece was so highly complicated. Leslie Jones, the editor, was there the whole time assembling scenes so that what was working and what wasn’t working really came into focus. We made key choices about the shape of the movie while we were in production, so that by the time we got to post the major building blocks were really in place and it was just about figuring out how much voice-over is too much, getting the music in there, picking takes, asking when is a good time to get ahead of the audience, when’s a good time to let them catch up — the regular old-fashioned choices you make in the editing room. On this one too, there were times where we were laughing hysterically and then we’d show it to friends and there’d be crickets, so you have to take that stuff out. But the way we did it, reshaping the movie as we went with Leslie so heavily involved during shooting…I didn’t really stop to think about it until now. It’s really strange.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD and iTunes. He also hosts a monthly podcast series on the American Cinematographer website and serves as a programming consultant at the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles.