Back to selection

Back to selection

NYFF Critics’ Notebook: Paul Thomas Anderson’s Junun

Junun

Junun I don’t think it’s unreasonable to speculate that any director, following his second ambitious, divisive high-profile theatrical underperformer/probable money-loser (or anyone fresh off a recently completed production, really), might generally welcome a chance to get out of town. It’s unclear how far in advance Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood planned to go to Rajasthan to collaborate on an album with Israeli-born, Indian-residing Sufi convert Shye Ben Tzur, or whether Paul Thomas Anderson initially committed to tagging along; regardless, it seems to have been restorative fun. Junun is a 54-minute music doc in which Anderson shoots whatever he wants, however he wants to. There are five credited camera operators, including Anderson himself and Radiohead’s regular producer Nigel Goodrich, along for the engineering ride. The celluloid purist plunges into his first digital feature, seemingly thrilled at the chance to repeatedly strap the camera to a helicam soaring above the former fort where recording takes place. One of the musicians gives it a genial wave on its initial ascent; later, the camera dives from above (nearly) into a flock of large birds semi-aggressively swooping in on pieces of stew meat tossed by one of the musicians. The camera mount can sometimes be seen, the operators spotted; Anderson doesn’t seem bothered.

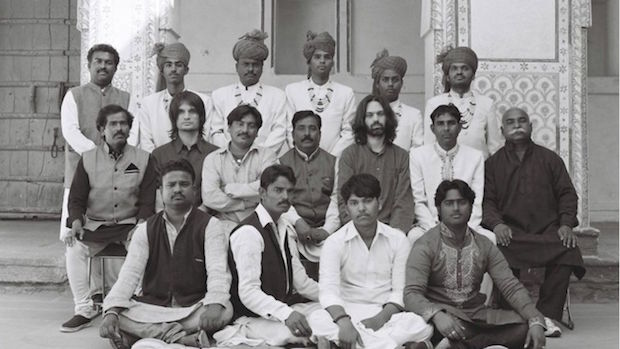

Junun‘s opening shot is a lateral right-to-left-and-back-again pan, taking in the musicians at silent rest in deference to a prayer call, basking in the mild-blowouts occasionally caused by sunlight (it’s very close to The Master‘s strong backlighting). The film launches into its first number with a bracing, somewhat unnerving drum thwack. (Anderson likes at least one good opening-stretch jolt per film: the car accident and banged-down harmonium in Punch-Drunk Love, the dynamite explosion in There Will Be Blood, Hoffman’s barked off-camera interrogations in The Master.) The camera is planted in the center of the circle of musicians and performs a full 360, with the mix successively dominated by instruments as they grow closer, highlighting and visually isolating each of the 21 musicians’ contributions. It’s loud, rhythmically compelling and ends with a percussive bang, a perfect set-up for a bold, unexpected title card.

Each Anderson film feels like a self-conscious attempt to not settle into a recognizable style or riff on its predecessor. Acclaimed for his profane, motormouth dialogue, Anderson made the first reel of Blood wordless and cut the number of lens flares from Punch-Drunk Love by ~90%. Blood was a masterclass in widescreen composition, so Master was composed in screen-filling, 1.85 close-ups counterbalanced by intensely controlled camera movement. Inherent Vice was technically comparatively shambling in expanding on the extreme-close-up heavy nature of The Master, setting up simple static-ish or push-in shots executed in somewhat dowdy service to the performers, but it was still captured on film; Junun makes for a clean digital break and opportunity to freeform indulge and execute a variety of inconsistent camera strategies. (The perspective is unavoidably a little tourist-y out on the streets, which is OK, and seeing the process of harmonium repair is certainly a novelty.)

Junun splices Anderson’s previously characteristic high formality and Big Event shots with Inherent Vice‘s handheld looseness and some other modes, both familiar and new. Between helicam ascents, Anderson executes some faux-Steadicam coups, roaming at virtuosic and kinetic will through the old fort (shades of Boogie Nights and Magnolia, moves he’s removed from his visual vocabulary for some time), or slowly panning over to rest on whatever musician he finds most compelling at the moment, confirming them as the most interesting person in the room at that moment. There’s a well-balanced tableau shot of the musicians mid-song from another room, disrupted and reframed by three different archways in the middle ground. After a few minutes of this impressive composition, the camera is suddenly hoisted up for a closer-up view, briefly lapsing into grab-your-phone-and-stare-at-the-ceiling chaos; this is the work of someone who’s going to do whatever they want, even if it’s momentarily disruptive and borderline amateur hour.

As in Frederick Wiseman’s Boxing Gym — a portrait of an athletic facility in which a diverse group of Austinites co-exist in unforced harmony — there’s a vaguely utopian feel to the recording sessions, which bring together a diverse group of Indian musicians from different traditions for productively syncretic purposes, many of whom are given their democratic moment in the narrative spotlight. (As Greenwood has described it, Tzur’s music is “intensely devotional Sufi poetry[,] sung mostly in Hebrew by Indian singers (though some songs are in Urdu and Hindi).”) The film feels like a relaxed opportunity for Anderson to play in a congenial, unstressed setting, a surely welcome opportunity to blow off steam now that Anderson has joined Alex Ross Perry (Winnie the Pooh) and David Lowery (Pete’s Dragon) at the Disney Reassignment Center For Niche Market Directors. By committing to script work for Robert Downey Jr.’s long-developing Pinocchio redux, he’ll presumably have to rein it in for a bit. Meanwhile, this non-major-work is an opportunity to revive and revise past styles, a chance to look forward a bit, and a no-pressure space to experiment.

Junun will be available for subscribers to stream on MUBI starting at midnight, October 8; more info here.