Back to selection

Back to selection

“I Made It Clear That I Wasn’t Just Going to Repeat How Evil He Was, That This Wasn’t a Rosenberg Revenge Film”: Ivy Meeropol on her HBO Doc Bully. Coward. Victim. The Story of Roy Cohn

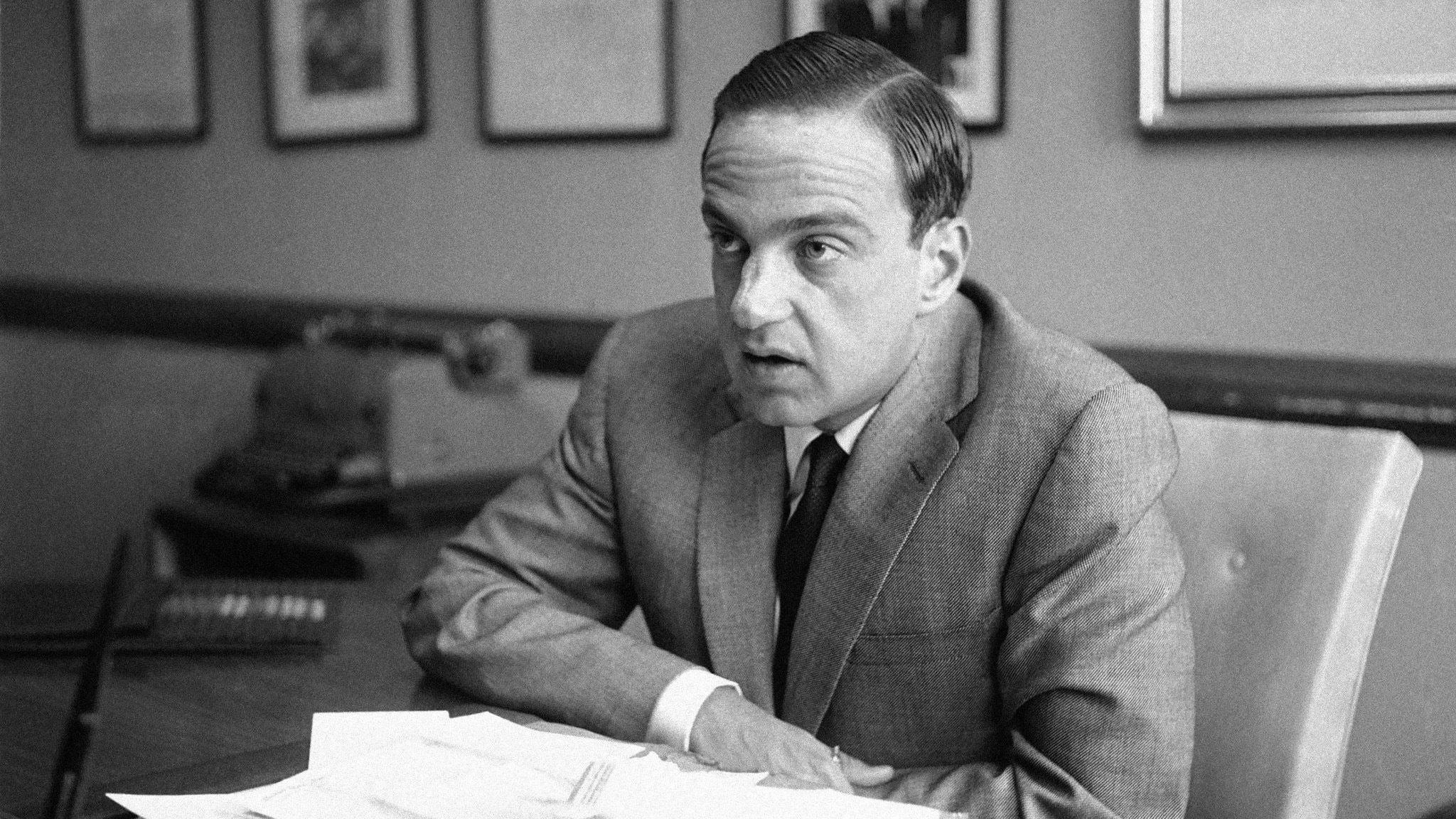

Roy Cohn in Bully. Coward. Victim. (Photo: Dan Gross/HBO Documentary Films)

Roy Cohn in Bully. Coward. Victim. (Photo: Dan Gross/HBO Documentary Films) I suppose it should come as no surprise that since the election of Donald Trump, Roy Cohn’s seemingly inexhaustible 15 minutes of fame have been extended yet again. Before his death from AIDS (or what he termed “liver cancer”) over three decades ago, Trump’s longtime mentor/lawyer/power broker/enforcer had spent his entire life reincarnating himself. Somehow the closeted homosexual and chief counsel to Senator Joseph McCarthy during the infamous Red Scare transformed what should have been an existence defined by shame into one of pure shamelessness — living the Studio 54 highlife with his mobster and celebrity friends, and never missing the opportunity to mix shady business with hedonistic pleasure.

But for director Ivy Meeropol (Heir to an Execution), who takes a deep and illuminating dive into this enigmatic, law-evading man’s life with her latest HBO doc, Bully. Coward. Victim. The Story of Roy Cohn, the brazenness is not only galling but personal. For Cohn first shot to fame straight out of law school with his prosecution of “atomic spies” Julius and Ethel Rosenberg — Meeropol’s grandparents. Their execution left her father and uncle orphans and spawned a legacy of heartbreak passed down to this very day.

Filmmaker caught up with Meeropol to find out more about her uniquely personal take on a man who shaped history in all the wrong ways prior to the film’s airdate on June 19th — the 67th anniversary of her grandparents’ execution.

Filmmaker: So Roy Cohn has been extensively covered in the media — indeed, he has become the go-to guy for the personification of evil at least since the debut of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America . What aspects did you feel had been missing from the Roy Cohn narrative that led you to decide to make this doc?

Meeropol: I think I could expand upon the powerful theme of fear and self-loathing turned outward in the form of Roy Cohn — that Kushner explores in Angels in America — by looking more closely at what a burden it was for Cohn to hide his true self. Exploring his time spent in his beloved Provincetown allows us a window into the world where Cohn was clearly happier being more open about his sexuality. And we took pains to craft that section in a way that allows audiences to feel what it might have been like to be Cohn during those periods of his life. Then, when we reveal that he fought against gay rights in NYC and beyond, aligning himself with vicious anti-gay reactionaries like Cardinal Spellman (also rumored to be gay), the impact is even greater as the incredible hypocrisy is made clear.

Yet the cumulative effect of understanding the context of the times and the world he lived in makes us uncomfortable just calling him evil. This complicates the idea that Cohn is the personification of evil. It forces us to reckon with societal bigotry, both institutionalized and otherwise, that is a greater problem than Cohn himself. Likewise, exploring how Cohn cared what the Jewish community thought of him, through what Alan Dershowitz tells us in the film, also allows us to see how Cohn’s fear of being painted as a “bad Communist Jew” made him the red-baiting fear monger we know him to be. He lived in an intensely homophobic and anti-Semitic world, and how he dealt with that informs so much of who he became.

I would also say that digging deeper into Cohn’s role in helping introduce Donald Trump to the national and international political stage had not been fully explored before. We now know that Cohn can be credited with delivering this completely unfit and dangerous person to the White House.

Filmmaker: What are the pros and cons of being so personally intertwined with your material? Do subjects open up more, or hold back, when speaking with the granddaughter of Roy Cohn’s victims?

Meeropol: The pros are that I feel a sense of ownership over the story and my connection gives me an entree into it that I can feel confident no one else has. Being personally intertwined also pushes me to work against that connection, because I don’t want it to overwhelm the discovery process and storytelling. Having the personal connection seems to make me work very hard to combat those preconceived notions and feelings about a subject, which in turn I think makes for a more complex treatment of Cohn.

It depends on the subject, but it’s certainly true that some participants acknowledged that they wouldn’t normally even grant an interview about Cohn, but because it was me they felt it was important to. I also get the feeling at times that some people are as interested in meeting me as I am them. So that certainly helps to open doors, but also relaxes them and gets them to open up once we’re shooting. That said, I ran into problems gaining access to some of the people closest to Cohn who were, not surprisingly, uncertain about my motives and my approach. I’d have to work hard to reassure them that I wasn’t doing a hatchet job on Cohn. And that still didn’t persuade everyone I wanted to participate.

Filmmaker: So how did you decide which characters to include in the film (and ultimately convince them to do so)? Your father is an obvious choice, but seeing Roy Cohn’s living relatives speak so frankly about him is quite startling.

Meeropol: We looked for anyone and everyone who knew Cohn, or had crossed paths with him in a meaningful way. I never wanted to use experts or academics to tell us about Cohn. Tony Kushner and Nathan Lane are the only subjects who did not meet Cohn, but they serve another purpose of course.

What was also important in choosing our characters was that they be great storytellers themselves and also have strong anecdotes that help us to understand how Cohn operated in both minor and major moments in his life. I convinced our subjects to participate by sharing my record as a serious documentarian. And for those who were Cohn friends or allies I made it clear that I wasn’t just going to repeat how evil he was, that this wasn’t a Rosenberg revenge film.

Filmmaker: One of the scenes that stuck with me was the interview with columnist Cindy Adams, in which she forthrightly admits that she wrote stories at the behest of her friend Cohn. Her lack of remorse, her blithe enabling, is just something I found especially chilling. Considering that you’ve lived in the shadow of Cohn for your entire life, did you uncover anything that particularly surprised, or unduly disturbed, you?

Meeropol: Finding out that the guy whose only job was securing cash-only parking lots for Cohn was killed off by the mob as soon as he was the subject of federal investigation was chilling. Also, Cohn’s ability to turn his former enemy Robert Morgenthau into an ally willing to use the power of the US Attorney’s office to send Richard DuPont (who was harassing Cohn) to jail for 18 months disturbed me as well. Especially to hear that he’d probably have had him killed too if it “wasn’t so obvious.”

Filmmaker: Your connection to history has certainly informed your prior work (i.e., Heir to an Execution), which makes me wonder if you view making films like this latest as a family responsibility, a burden, perhaps a bit of both?

Meeropol: At various times in my life I have felt that my family legacy has been both a responsibility and a burden. I felt compelled to make Heir to An Execution and never thought I’d return to our family story in my work. So even though I was fascinated and recognized what an important story Cohn’s life was, that it certainly deserved a full documentary treatment, I was reluctant and hoped someone else would take it on. It felt more of a burden than a responsibility.

But once Donald Trump was elected I knew it had to be my next project – because the ghost of Roy Cohn was moving into the White House and I knew what that meant. I then felt a responsibility to use my personal connection as a way into the story and a way of framing it. Exposing myself and my family is never easy, but sometimes if feels essential.