Back to selection

Back to selection

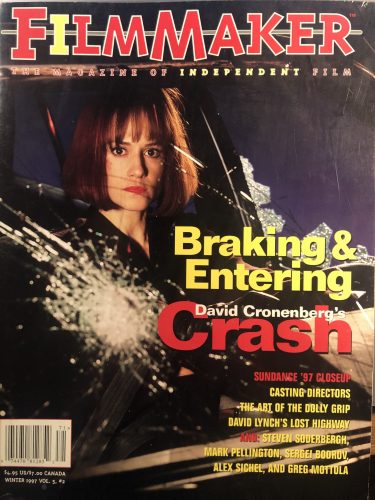

Braking and Entering: Director David Cronenberg on His Austere and Unnerving J.G. Ballard Adaptation, Crash

James Spader in Crash (Photo: Criterion)

James Spader in Crash (Photo: Criterion) The following interview with David Cronenberg about his film Crash originally appeared as the cover story of Filmmaker‘s Winter, 1997 edition. With Crash having just been rereleased in a new restoration by Criterion, it is being republished online for the first time. Also regarding Crash: Joanne McNeil’s essay on the relation of the work to the source material, J.G. Ballard’s novel.

Blood, semen and gasoline are the liquids that course through David Cronenberg’s compelling study of sexual fetishism, Crash. But far from being a, well, messy affair, Crash is startling for its cool precision and astute manner of intellectual provocation. Adapting J.G. Ballard’s 1973 cult novel about a group of jaded urbanites who eroticize automobile crashes, Cronenberg has made his best film since Dead Ringers, an austere, minimal, yet emotionally moving romantic suite — of sorts.

In Crash, James Spader plays a character named Ballard, a film director whose sex life with wife Deborah Unger has reached a dead end. When he accidentally smashes his car into Holly Hunter’s vehicle one night, killing her husband in the process, a paraphilia is unleashed among the three, traveling among them like the mutant virus creatures of such earlier Cronenberg films as Rabid and Shivers. The characters’ growing obsessions lead them to Vaughn (Elias Koteas), a sort of rebel leader of car-crash fetishists.

After winning a special award for “audacity” at the Cannes Film Festival, being banned in London cinemas by the local city councils, and denounced by New Line owner Ted Turner, Crash is scheduled to open this Spring through New Line’s arthouse label, Fine Line Features.

Filmmaker: You originally read Crash years ago. Picking it up and re-reading it before writing the script — how did the intervening years affect your approach to the material? Did you film it differently than you would have around the days of, say, Rabid?

Cronenberg: It’s difficult to know how you change in terms of your filmmaking. Obviously, you hope you’re getting better and more mature, but maybe not. I didn’t re-read the book carefully because it’s been my experience that you have to be prepared to betray the book in order to be faithful to it. It sounds like a paradox, but it really isn’t. The two media are so different that if you try to be literally faithful, you will fail. So you have to adapt that you are making a new thing for the screen that will have its own life and that’s going to be filtered through your nervous system, your sensibility. And with Crash I really thought I was going to have to do what I did with Naked Lunch — do sort of a construct. Naked Lunch isn’t really just the book, its Burroughs’ life and this other preface that he wrote — all these other things. But to my surprise when I started Crash, it distilled into film terms pretty directly. I found a cinematic essence that was not in Naked Lunch. There were continuing characters, character development. Certainly there is a distinct, unrelenting tone to the book. For me that provided a cinematic basis for the movie, although it’s true that the movie’s structure is not classical in any sense, anymore than the book is a classical Victorian novel. Crash sort of looks like a normal mainstream movie on the surface, but it doesn’t work like one, and that has caused some interesting confusions and perplexities.

Filmmaker: In terms of the story’s structure, one difference between the movie and the book is that the book incorporates this idea of spectacle and media mythology; towards the end, there is this big car crash involving Elizabeth Taylor. But in the movie about half-way through, the extras seem to vanish, and the movie becomes very claustrophobic, dealing with just these three people.

Cronenberg: It’s more like five, but yeah. But I don’t think of the book as [dealing with] spectacle. The desire of Vaughn to crash with Elizabeth Taylor and the fact that he almost does is told in a sort of off-handed way. We can talk about why I don’t have Elizabeth Taylor in the movie, but I found the book to be very interior. The police in the book are almost an abstraction. The book is not really concerned, as in a John Grisham way, with [portraying] the point of view of the investigating officer — [the idea] that the police represent social forces. I don’t think the book is really concerned with social forces as it is with interior forces, so I feel I’ve actually been faithful to the book that way. There aren’t a lot extras in the movie. I had this poor A.D. who kept saying, “I have these hundred extras. Should I put them on the streets, bring the streets alive?” And I kept saying, “No I don’t want them.” Basically I felt my process [in making the film] was the same as Ballard’s. It’s a little like going back to Godard’s invention of the jump cut — saying, “Whatever’s boring and doesn’t interest me, I’m just going to ignore completely. It doesn’t exist. I’ve done that and I think Ballard’s done that too. I don’t really want to know what a passerby in another car might think of this hooker in the back seat of [Vaughn’s] car. If the movie were realistic in whatever terms we understand that to mean, we might expect [to see] that reaction, and it might be a source of amusement. The movie, like the book, is very austere, very distilled, and that gives you part of its tone. Even thought the details with which we choose to do this change from book to film, I think the process is the same.

Filmmaker: There’s always been that kinship between Ballard and the surrealist artists, the idea of the exterior world as a kind of projection of the subconscious —

Cronenberg: Yes! Exactly.

Filmmaker: But Ballard was certainly interested in the 20th-century landscape and its relationship to psychology. I can understand not having Elizabeth Taylor in the movie, but what about billboards, advertising, the media —

Cronenberg: Television —

Filmmaker: Right. That’s not in the movie at all.

Cronenberg: That’s correct. And I feel that I must say its presence isn’t particularly dynamic in the book either. Elizabeth Taylor — even Elizabeth Taylor isn’t Elizabeth Taylor anymore. She does not that that iconic Hollywood value she had 25 years ago. To have Vaughn crash with a 65-year-old lady does not have the same meaning!

Filmmaker: But you could have had Sharon Stone in there or something.

Cronenberg: I don’t think you could. I don’t think the Hollywood icons now have the same function or power they had then. They’re not the same. Also, to turn Vaughn into a celebrity stalker, which wasn’t exactly a fixed category when Ballard was writing but has become one now, would diminish him. I wanted him to be more slippery and difficult to pinpoint. So those were the two main reasons I got rid of that whole “stalking Elizabeth Taylor” routine and substituted James Dean — safely dead, safely a ’50s Hollywood icon.

Filmmaker: Picking up on term “realism,” it’s struck me that if you make a move about extreme subject matter, if the film has some relationship to the real world, people know how to react. For example, people may have been shocked by Kids, but the idea that the film represented some sort of education regarding “kids today” allowed them to deal with it. The horrors of Crash, on the other hand, arise from the imagination, and that seems much harder for people to deal with.

Cronenberg: It is. But you cannot separate movie reality from structure. The Hollywood movie has been the predominant mode of moviemaking since the dawn of cinema. Now even more so. And people come to a film with the “Hollywood filter” on. One critic said to me, “What I find most disturbing about your movie is its lack of a moral stance.” But in most movies, the moral stance is just a narrative device. The characters have to be outraged, the moviemakers have to be outraged, but it’s a device. Most people know that no one making the movie gave a damn about the subject matter, was not outraged, could care less about it. Part of what this movie is about is: What if you don’t have that moral stance? What is all the moral stances are false? Or at least belong to the past and are no longer valid — a truly existential take on modern life. We have no values. We can create any value we want. So to take a moral stance would be to completely betray the undertaking of the film. That’s the most exciting thing you can do; rather than go in with a message, say, “I don’t have a message.” And that [idea] is not part of the Hollywood filter.

Filmmaker: The succession of sex scenes opening the film isn’t part of the “Hollywood filter” either.

Cronenberg: There are some very interesting formalist problems that happen with this film. The fact that it begins with three sex scenes in a row completely freaks people out. Either they laugh or get upset and don’t know how to deal with it. Because some people have never seem multiple sex scenes except in a porn film, they presume that the movie’s porn and react to it [accordingly]. They’re not seeing everything that’s being developed in these scenes, the conjunction of the different scenes.

Filmmaker: How does the concept of pain differ from film to literature?

Cronenberg: Once again, the two media are so completely different, they do not replace each other. In fact, they barely overlap as far as I’m concerned. And one of the things that even a Danielle Steele can do is interior monologue. The voiceover [in film] does not create the same effect. In film, to have someone in pain talking about their pain is not the same. A scene of torture is very difficult to film [in a complex manner] rather than as a physical, hideous event that you’re watching and squirming over. To convey the subtleties going on in Crash, where pain is totally consensual and quite complex, I immediately became not literal [in the filmmaking]. The soundtrack becomes very important, and the rhythms of the cutting start to convey some of what is being experienced. Because film is so literal and physical, you have to work hard to overcome that.

Filmmaker: I know Crash had a smaller budget than some your other films. Did you have to go back in terms of an earlier working method?

Cronenberg: I did go back to an earlier working method, but it was because of the nature of the film, not the budget. Crash was much more like shooting Scanners, say, than shooting M Butterfly. The budget always feels the same: you don’t ever have quite enough. It doesn’t matter how big it is. You feel like you’re shortchanging yourself but because you’re clever, you’re not really. And you’re trying to make advantages out of things that might be considered disadvantages. But every movie’s like that. We were shooting on the streets, at night, in the cold, and having to use a lot of ambient light because we couldn’t afford to light up five miles of highway. The scenes at the end, in the rain at night — that was real rain. There were 35 stunt drivers and 35 stunt cars on the road at night. And we just incorporated [artificial light] when we could, like pumping up the car headlights, to give [the film] a controlled look and feel. And we got roads that were very well used in Toronto [rather than] a [brand new] highway being built, the 407, that we could have had. I wanted a used look and texture. So that’s a choice. You don’t have unlimited control or access, but you’re getting something else instead: the texture, the wearing, the rust. About the only thing I can say specifically is that I didn’t know know whether I wanted to see Vaughn’s final crash, but I would have tried it if I could have afforded it. But I couldn’t, so I decided to have it happen off-camera and do a tableaux.

Filmmaker: How did you approach all the car work?

Cronenberg: I really wanted to avoid the cliches of an action picture, so there are no slow-motion shots and you don’t see everything repeated from five different angles. One of the conceptual problems in making this film was dealing with action-movie logistics without making an action movie. I had to do the hard part without getting the goodies. I still had those 35 stunt drivers and hard to choregraph them but also say, “I don’t want the car to flip. I don’t want to film it flying in slow-motion in the air and then explode.” And even just where I put the cameras on the cars — I mean, two of the most photographed things in the world must be sex and cars. So it’s in the subtleties; when people say they’ve never seen are photographed this way before, I love that. You may have seen those shots in a commercial, but it’s the way the camera angles are used relative to the dialogue that gives it the off-centered tone. Once again, that has nothing to do with budget. You’re going to have to put the camera somewhere.

Filmmaker: Did you build special car rigs?

Cronenberg: Oh, tons. We had six Lincolns and I cut one of them in half and made a pickup truck so that the deck and the back seats and the trunk were all gone. We could do camera moves and carry lights and generators. We built very elaborate light tubes over the Porsche to do some lighting. But it’s pretty invisible. We wanted it to blend in so you don’t feel a disjuncture between a very plastic studio look and a more ambient light look.

Filmmaker:How did you cast the cars?

Cronenberg: I really had to fight my car-enthusiast tendencies. I gave the Ballard character a very boring car — a Dodge Dynasty, although we used our own symbol for it. I din’t want it to be exciting. Wired magazine called Jacques Villeneuve, the Canadian racer, the ultimate man-machine interface — he’s so embedded the car into his physical being that he doesn’t think about it. That’s what I wanted to suggest by giving Ballard a boring car.

Filmmaker: What’s the emotional effect of making a controversial film?

Cronenberg: I don’t like it. I don’t know if Oliver Stone really enjoys what he does in terms of controversy. I feel without ever having met him that maybe he is a more combative and confrontational kind of person than I am. And maybe he’s truly gleeful when he upsets people. I’m not. If everyone who saw Crash said, “I enjoyed it,” I’d be perfectly happy. What happens in the UK, where you see the press deform the film before your very eyes, demonizing it, turning it into something it is not — that is very depressing. In France the [film prompted] some good healthy debate about what the cinema should do and sexuality. That’s exciting. But this whole idea that any publicity is good publicity is not true. Talk to Salman Rushdie.

Filmmaker: There are a lot of sexual fetishes in the world but getting off on car crashes is not one of the common ones.

Cronenberg: No.

Filmmaker: You can’t go to the internet and find alt.sex.carcrash.

Cronenberg: You probably will soon.

Filmmaker: To what extent did you research whatever real-world analogue to Crash may exist before filming?

Cronenberg: Not at all. I mean, the film works on such a non-literal level that it’s really irrelevant. What Ballard is saying is not that car crashes are sexy. It’s that there is a deeply hidden erotic element to the event of the car crash. I believe that is true, and that is what we are talking about in the movie. But it’s so difficult for people to get their head around it. Somebody will say, “I’ve been in a car crash, and it’s not sexy.” I heard of this psychiatrist who said, “Yeah, I deal with one of these guys every week. He seeks them out [car crashes] and stands around and gets sexually aroused.” To me this has almost nothing to do with the movie, bizarrely enough. The movie has more to do with the relationship between sex and death — the fact that when we are endangered physically we are also aroused sexually. There’s a very old primordial trigger: members of your species are dying, so you should become sexy so you can mate and procreate. Sex and death. Thanatos and Eros. Understood for thousands of years — not by UK journalists, mind you. It’s a very complex interrelationship. On that level — mortality and death — you find the meaning that makes sense in the movie.