Back to selection

Back to selection

“Being an Outsider to Palm Springs Was an Asset”: Sara Newens, Mina T. Son and Courtney Parker on Racist Trees

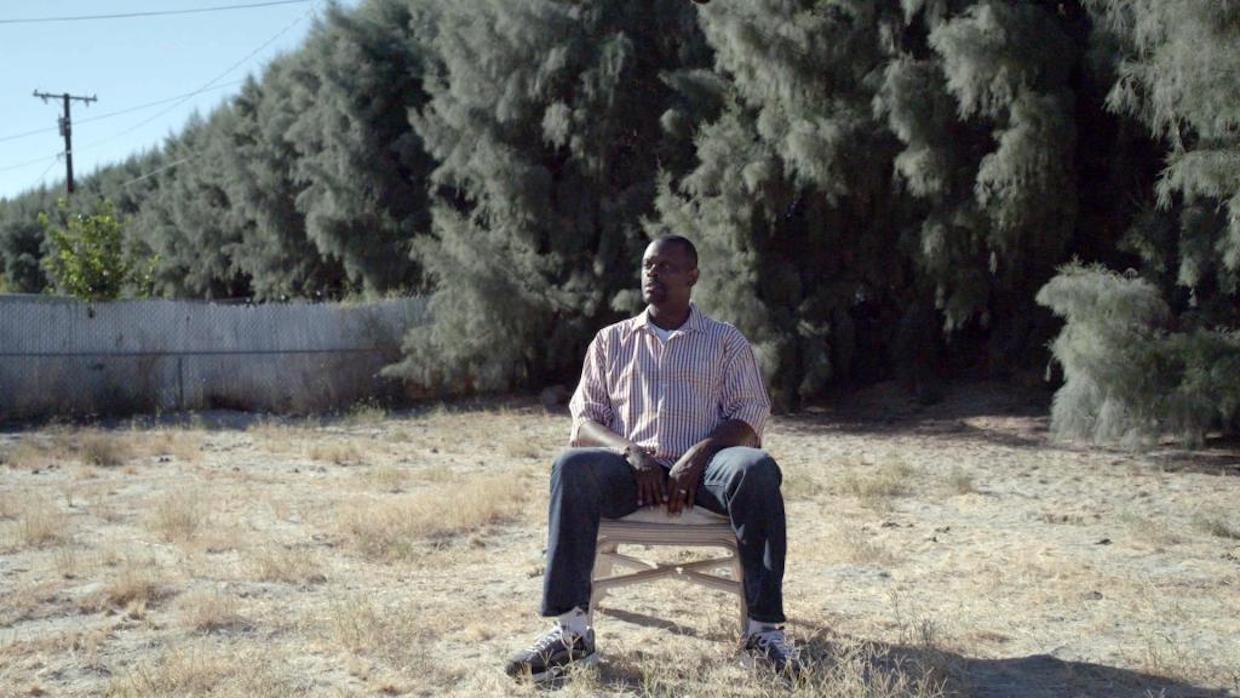

Racist Trees.

Racist Trees. Sara Newens and Mina T. Son’s provocatively titled Racist Trees begins as an innocent investigation into the root (no pun intended) of a half-century dispute over a line of 60-foot tamarisks separating a historically Black section of Palm Springs from its historically white (and now overwhelmingly gay cisgender male) neighbors on the other side of a city-owned golf course. The film morphs into something much more shocking than merely another example of systemic inequality and the longstanding “polite” racism of white liberals who prefer gaslighting to admissions of culpability. Indeed, in the slyest and boldest of moves, the white and Korean American filmmaking duo (along with their Black co-EP and DP) have taken what appears to be average tale of two cities and transformed it into a laugh-and-cringe, Jordan Peele-style, comedy-horror doc.

Soon after catching the film during its world-premiering IDFA run back in November, Filmmaker decided to reach out to the team—director-producer-editor Newens, director-producer Son and co-executive producer Courtney Parker—as they prepared for their doc’s North American debut January 7th, appropriately during the Palm Springs International Film Festival.

Filmmaker: Could you talk a bit about how this project originated?

Newens: After Mina and I finished our last feature, Top Spin, which was filmed in five different countries on four continents, we were really interested in pursuing a story much closer to home. So, we started paying closer attention to local and regional news stories. That’s when we came across an article from The Desert Sun about a wall of 60-foot tamarisk trees in Palm Springs that separated a historically Black neighborhood from the rest of the city. Pretty immediately, it was clear to us that these trees would be a striking visual metaphor for the stark contrasts within race and class in what is more widely known as a very progressive town.

Son: That Desert Sun article was also incredibly well researched by the reporter, Corinne Kennedy, who had already spent months investigating. She concluded that the majority of the residents of the Lawrence Crossley neighborhood felt excluded by the trees, and believed they were originally planted in the late-1950s with racist intent. But there was also a bit of a mystery to uncover there: Who actually planted these trees and why? That led us down a deeper path that unearthed an even more complicated past between the city and its BIPOC communities. That’s when we knew there was a larger story to tell around systemic racism, privilege, generational wealth and gentrification.

Newens: Yes, we knew pretty much from the start that the mystery surrounding the planting of the trees was a bit of a MacGuffin, but would serve as a microcosm to look deeper into issues at play across the entire country. Especially when taking into account how deeply hesitant city leaders were to even acknowledge the trees as a vestige of racial discrimination, there seemed to be a lot more concern around being labeled “racist” than the impact of racism itself.

Son: Initially, this project started off with no funding, and was really just a way for Sara and me to collaborate again. A year or so in, our friend Joanna Sokolowski joined us as a producer. Then, in 2021, our production partner Wayfarer Studios came onboard, which is how we were introduced to our co-executive producer Courtney Parker.

Parker: Given the subject matter of the project, it was important to Wayfarer Studios, as well as to Mina and Sara, to have a person of color on the team that could help provide a Black perspective, especially on the ground in Palm Springs and within the Lawrence Crossley community. Collectively, we wanted to ensure that all voices were represented, and bringing me onboard helped to achieve just that.

Filmmaker: How did you gain the trust of the community? I know you’re Los Angeles-based, but does anyone have a specific connection to Palm Springs?

Son: I’ve lived in Southern California my whole life and Los Angeles for the last 11 years. Like for many people who live here, Palm Springs has been a fun getaway. Sara and I had also attended film festivals in the area, so we both shared a soft spot for the city, which is why we wanted to learn more about the Lawrence Crossley neighborhood—we hadn’t heard of any stories about communities of color in Palm Springs. We realized this was clearly a blindspot for us, and likely for others. So, we reached out to Corinne Kennedy, who was generous enough to connect us directly with the residents with whom she had established relationships while reporting.

Newens: Fortunately for us, everyone from the neighborhood we initially spoke to was pretty fired up about many things, but in particular the injustice of just how much these trees had been depressing property values for the entire neighborhood. I also think that many residents were aware that any additional media coverage and exposure might help put pressure on local leaders to get the trees removed.

Parker: There are always commonalities within communities of color with [individual] people of color and diverse backgrounds—an understanding that even if we haven’t gone through the same thing, we’ve all encountered a shared experience in one form or another. Although there was an extreme appreciation for what Mina and Sara were doing with the film, once they realized I was onboard, there was a greater sense of trust that expanded the reach and access for the project at large.

Filmmaker: Sara is white, Mina is Korean American and your DP Jerry Henry is Black, which made me wonder how this affected access to these segregated factions. I was just thinking that Jerry shooting interviews with self-declared “not racist” whites might actually make those folks less forthcoming, though I guess that also adds to the doc’s absurdist humor.

Newens: Every person is going to have a unique relationship with the camera depending on the folks who are behind it, but I do think being an outsider to Palm Springs was an asset in a way. Our goal was really to remain as neutral as possible while in the field, and to hopefully create a space in which everyone who wished to share their perspective could do so.

Son: Sara and I also both feel strongly about diverse representation behind the camera, but it was especially important for this film to have Jerry as our DP and Courtney, who was in the field, helping us produce. She was instrumental in developing trust with the community.

Parker: Early on, I personally heard many members within the community speak with some caution about providing us with the proper access to things that would help with the film. There will always be certain biases and blindspots we all face. For the Lawrence Crossley neighborhood, I believe I was able to provide a real sense of comfort and relief on both sides.

Filmmaker: Have all the participants seen the final film? If so, what have the reactions been like?

Newens: We have offered everyone a chance to watch the film, and most of the main participants have seen it. So far everyone seems to be pleased with the many perspectives that are represented, even as many of these folks have opposing views.

Son: I think for the Lawrence Crossley residents in particular, they are happy that their story is being told to a wider audience. After decades of feeling ignored, I believe there is some vindication that all of their efforts—and past generations’ efforts—have not been wasted. And we are thrilled the film is screening at the Palm Springs International Film Festival, where there will be an opportunity for the neighborhood to watch and celebrate their efforts together, but also have a platform to continue the conversation with the larger community.

Parker: Everyone I’ve spoken to regarding the film has been extremely proud of the end result, and especially the conversations that the film is capable of igniting. With the growing awareness and media coverage on how communities of color were impacted by forced evictions in the 1950s and ’60s, there are even talks of reparations happening now with the city—and a social justice effort, led by the Section 14 Survivors group—in order to impact real change within Palm Springs.

Filmmaker: Since you world-premiered Racist Trees at IDFA, I’m also curious to hear what the international audience reaction has been. (Especially since “liberal” Amsterdam also hosts its annual Sinterklaas parade every November, in which locals often dress up in blackface to portray the minstrel-like “assistant” Zwarte Piet, yet still insist the tradition isn’t racist.) Do you expect it to be similar or markedly different in Palm Springs?

Newens: Given how hyperlocal our story is, we weren’t sure initially if the film would translate overseas, but we have been pleasantly surprised. In fact, it seems the discussions around Sinterklaas and Zwarte Piet may have even factored into the programmers’ decision to screen Racist Trees at IDFA. It’s a very popular festival among locals, and there were several audience members who expressed to us how the various issues and themes of the film really resonated.

Son: While it was very exciting to hear the European perspective, unfortunately, issues of racial and systemic inequities are everywhere—as is white privilege. Oftentimes, some of the worst offenses are in so-called “liberal” spaces. But our greatest hope in making this film has always been to spark more honest conversations about race, even when it is difficult and uncomfortable.

Parker: I agree with the ladies. We were all collectively aligned in hoping to make people comfortable while having uncomfortable conversations about race, race relations and topics that are happening around the globe. Because the film consciously picks an angle with a lighter stance, it creates a platform for people worldwide to start and have the necessary conversations to promote change.