Back to selection

Back to selection

Lee Isaac Chung, Munyurangabo

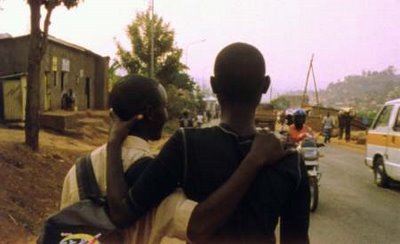

ERIC NDORUNKUNDIYE AND JOSEF “JEFF” RUTAGENGWA IN DIRECTOR LEE ISAAC CHUNG’S MUNYURANGABO. COURTESY FILM MOVEMENT.

ERIC NDORUNKUNDIYE AND JOSEF “JEFF” RUTAGENGWA IN DIRECTOR LEE ISAAC CHUNG’S MUNYURANGABO. COURTESY FILM MOVEMENT.For Lee Isaac Chung, filmmaking is linked to tackling challenges and obstacles above and beyond those inherent to the cinematic process. The son of Korean immigrants, Chung was born in Denver in 1978 and grew up on a farm in rural Arkansas. He attended Yale and was studying biology, on track to become a doctor, when he discovered arthouse movies. Rather than continue on his path to a medical career, Chung took a filmmaking class given by Michael Roemer and went on to earn an MFA in film from the University of Utah in 2004. A classmate at Utah, Yohei Kawamata, became the star of Chung’s first two shorts, Highway (2004) and Sex and Coffee (2005). In his work, Chung has been attracted to projects in other languages: in 2005, he made the Spanish language short Los Coyotes about immigrant smuggling, and in 2007 he completed his long gestating documentary about Chinese Christian preachers, Six Days – despite the fact that he speaks neither Spanish nor Chinese. He is currently in post-production on his first English language feature, Lucky Life, which was chosen as one of the participants in the Cannes L’Atelier du Festival initiative in 2008.

Chung’s debut feature, Munyurangabo, continues the writer-director’s exploration of cinema beyond the boundaries of language. It was shot in Rwanda in just eleven days, and represents the fruits of a filmmaking course for aspiring Rwandan natives conducted by Chung. The film, the first in the Kinyarwanda tongue, tells the story of two young friends, Sangwa (Eric Ndorunkundiye) and Ngabo (Josef “Jeff” Rutagengwa), a Hutu and a Tutsi respectively, who leave the Rwandan capital of Kigali to go and kill the man who murdered Ngabo’s father during the genocide of 1994. On the way, they visit Sangwa’s family, and the bond of friendship between the two is tested by the intolerance and prejudice rooted in age-old ethnic divisions. Mostly improvised, and shot in a documentary style, Munyurangabo has a feeling of total authenticity and Chung and his actors imbue the fable-like story with deep emotional resonance. The film examines the repercussions of the genocide – and how to move forward from them – with a rare perceptiveness and compassion. Chung’s coupling of stylistic spareness with an emotionally complex narrative is highly effective, and this accomplished film leads us to hope for much more from him in the future.

Filmmaker spoke to Chung about his attraction to making movies in foreign languages, his role in bringing film culture to Rwanda, and how Chungking Express and Days of Heaven changed his life.

Filmmaker: What was the genesis of Munyurangabo? Did it start when you went to Rwanda in 2006, or prior to that?

Chung: My wife and I got married in 2005, right after she got back from a trip to Rwanda. Before the wedding she said, “Next summer I want to go back,” so I basically I needed to figure out something I could do while I was there. I thought, “Maybe teaching cinema would be interesting,” and then the only way that I think you can learn is to make a film.

Filmmaker: So was the film conceived more as a community educational project, or as a feature that you would make?

Chung: Initially I didn’t know if it was just going to be a short film or just some quick video project, so it was focused on the class. But when I started watching or reading up on certain films that had come out of Rwanda, I realized that maybe the greatest honor to do for them would be actually to treat the project very seriously and make a film that very much could be considered part of their national cinema.

Filmmaker: There’s been much made of the fact that you, as a Brooklyn-based filmmaker, made a very authentic film about Rwanda, its people and its culture. How did you go about doing that?

Chung: I guess it’s no different from making a documentary, if we were successful. After graduate school, I went to China and shot a documentary in Chinese – I don’t speak Chinese either. I did this and found that you can make a film by simply listening and observing and trying to interpret what you are seeing and looking for some sort of universal connection between you and another person, and using that as a starting point for how to shape a portrait of them. I didn’t have the audience in mind: I didn’t concern myself with “How is a Westerner going to look at this?” but I wanted it to be very true to a Rwanda person. The most important question was how do you truly present this individual or this subject matter in as honest of a way as possible? It’s a constant search and listening while you’re there.

Filmmaker: You had this group of Rwandan students, so how long was it before they were ready to make the film with you? Presumably you had to start from scratch with them.

Chung: It was six intensive weeks, then one week of production preparation, and then a week and a half of shooting – and then half a week to celebrate when it was done! [laughs] That was basically the breakdown of the schedule.

Filmmaker: Language was obviously a big factor in making the film. Did you have a translator with you?

Chung: Of the people I taught, two of them were very fluent in English, and then most of them were able to understand quite a bit. The actors I worked with didn’t speak English, so actually directing the actors took a long time, getting things translated back to them and to me. For the rest of the crew, I could just speak English and someone would translate here or there if they didn’t understand.

Filmmaker: How secure did you feel in that situation? What was it like not knowing what the actors were saying or when to tell them to cut, and not being able to rely on the usual processes of making films?

Chung: To be honest, Lucky Life was my first English language film in a long time. During graduate school I made a native film in Spanish – and I don’t speak Spanish – and then I shot the Chinese documentary, and then Munyurangabo, so I kind of got used to this process of working with a lot of language barriers. I grew up with Korean parents who don’t speak English perfectly and I don’t speak Korean very well either, so we got along quite well with limited communication. In filmmaking, it was actually a nice challenge and it’s nice to find certain cooperation and work together through language barriers. I feel like it’s a beautiful thing.

Filmmaker: On the surface, the challenges that you faced making this film seem incredibly daunting, but you seem to be saying that that’s what makes the who process worthwhile.

Chung: That’s exactly what I would say. I love traveling, especially to places where there are very few people who speak English. I’ve just always enjoyed that, so to work in that environment was just the next level. When I’m in Rwanda, I feel like I’m thriving in that environment. Some friends will come and visit and while we’re there they’ll find it very funny that I’m driving all around the country in this truck and hanging out with people who don’t speak English, stuff like that. I enjoy that quite a bit.

Filmmaker: I want to ask you about the writing of the script. Did you have a treatment and then had the actors improvise around it?

Chung: Yeah, we worked out maybe a 10 -page basic outline of the story and from there we had to find all the dialogue, all the details of the story, and that came about working with the crew and the actors improvising. It was an outline with numbered scenes, and some of those scenes were very sparse in the details, and would just say “Ngabo feels threatened,” We’d have to figure out how to do that.

Filmmaker: How easy was it to create those scenes through improvisation and rehearsal given that these weren’t actors with any experience or training?

Chung: It was much easier than I anticipated. We shot it in 11 days, and that just shows how quickly we were able to move. We were improvising during those 11 days, and the way in which I like to work is to have a rehearsal, and if I think it’s almost there then we shoot it. By the end, we would shoot without any rehearsals and it would be perfect. Of course, there were times that I would have to tell them to weed out certain parts of the dialogue if it didn’t make sense to the story, or if it didn’t work, just to scrap the idea and find another scene.

Filmmaker: It seems remarkable that with improvisation, with the language barrier and with such inexperienced actors and crew that you shot a feature in just 11 days.

Chung: I don’t know what it was, it just came together pretty well, and the crew and the actors were professional, and they were very clear about what they thought should go into the film and what was truly Rwandan, so it was able to rely on that quite a bit. Because of those limitations, they knew that they had to bring a lot more what they were doing in order to help me in what I was doing. There was an urgent sense of having a creative endeavor, mainly because they don’t have any other opportunities to make a film.

Filmmaker: You’ve gone back to Rwanda since to teach film again. What kind of a responsibility do you feel to the people who you worked with on Munyurangabo?

Chung: After making the film, I realized just how important it is to give them all the resources to make their own films. They often ask if I would come and direct another film, but I’ve been refusing and trying to put it onto other people. I’ve gone back two times since and I plan to keep going and teach these same students. The focus has definitely shifted to teaching and equipping them to be completely independent of me, and they’re doing quite well now. One of the students, Edouard [B Uwayo], the poet in the film, just made a feature film that played at their national mourning ceremony for the genocide in front of the president at the big stadium. Apparently it was a big success and [Paul] Kagame, the president, said that it’s his favorite film in the world. [laughs] He also got a grant from Focus Features to make this film, so it definitely feels like we’re on the right path to success.

Filmmaker: The film employs a simple documentary style a lot of the time, but you use slow motion and jump cuts interestingly as well in addition to using both indigenous African music and modern jazz.

Chung: I’m a believer in shaping the style around the subject. I think Lucky Life‘s style is very different from Munyurangabo. A lot of the long takes, for instance, were necessary to preserve the performances because it’s hard to improvise scenes using lots of cuts, and it was also to show the pace of life and the way time progresses. A lot of those choices come very intuitively, and at the same time there are multiple influences within the film. I think watching Kiarostami was quite important, and the way in which he filmed when he went into the countryside in films such as The Wind Will Carry Us. That was a very important film. Bresson, for instance, was influence too. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly. There’s no real theory behind why I use certain stylistic elements. There’s always some reason that goes into it.

Filmmaker: When you were at Yale, you were on course for a medical career when you discovered you wanted to make movies. What was your moment of realization?

Chung: Somehow, by chance I just watched Chungking Express, and growing up in Arkansas there is no such thing as arthouse cinema. You don’t get it at all. I also saw Days of Heaven. I remember thinking that both were such interesting films that I decided to read up on the directors. I noticed that Wong Kar-wai talked a lot about the French New Wave, and I thought, “Well, what’s that?” so I started exploring that, and watched The 400 Blows, Breathless. It was decided for me at that moment what I wanted to do. [laughs] Filmmaking seemed like a very impractical decision when I made it, but it just felt right.

Filmmaker: How did the people around you – and in particular your parents – react to such a radical change?

Chung: I think it was very difficult for my parents all the way until Munyurangabo got in Cannes. It showed up in a lot of Korean papers and I think they started thinking that maybe it was OK. [laughs] That was the turning point with them.

Filmmaker: When was the last time you burst out laughing on set?

Chung: That’s easy. I worked with this guy Yohei [Kawamata], who I went to grad school with, who has a small role in Lucky Life. He’s a stand-up comic so I had him improvise, and we have many out takes where he’s just saying things that I can’t repeat. That was the biggest laugh I’ve had in a long time.

Filmmaker: What keeps you awake at night?

Chung: [laughs] I’m always awake at night. I’m a very late sleeper. My temperament keeps me awake at night and I’m just unable to sleep.

Filmmaker: Finally, if you had an unlimited budget and could cast whoever you wanted (alive or dead), what film would you make?

Chung: [laughs] That’s a funny question. I’ve never entertained these questions in my head. Maybe if it’s now, I’d want to make something with Jérémie Renier. I really like him, he’s a great actor. I’d love to make a film with him.