Back to selection

Back to selection

“Blacklists,” Caveh Zahedi and Thom Powers

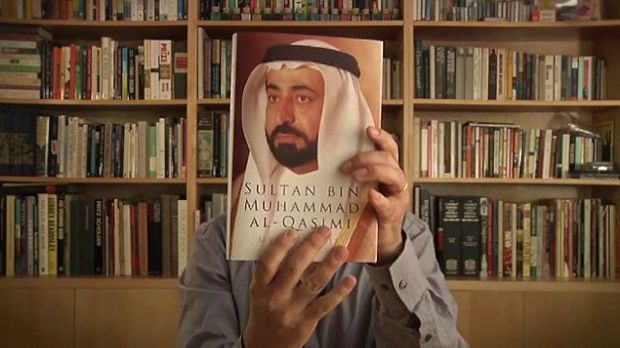

The Sheik and I

The Sheik and I As one of the three journalists contacted by documentary film programmer Thom Powers last Spring about Caveh Zahedi’s The Sheik and I, I wanted to weigh in on the controversy that erupted this week following Zahedi’s accusation that Powers has “blacklisted” his picture, which opens today from Factory 25. After watching Zahedi’s YouTube video and then reading Powers’ response, I decided to talk to both men to explore the situation in more detail. Then, in the midst of writing this, I noticed Eric Kohn’s post at Indiewire this morning, which exhaustively discusses the film, the timeline of Powers and Zahedi’s communication, and thoughtfully mulls the various ethical and aesthetic issues at play. I recommend you read it before continuing here.

To provide my backstory, I’ve been a longtime fan of Zahedi’s work. The very first article I ever wrote about independent film was about Zahedi and Greg Watkins’ A Little Stiff back in the old Off-Hollywood Report. Years later Filmmaker gave Zahedi our Best Film Not Playing at a Theater Near You Gotham Award for I am a Sex Addict, and my quote appears on the film’s poster. So, I was looking forward to seeing The Sheik and I, including it in a blog post listing 20 films I was anticipating at SXSW. (“Note to politically sensitive Middle Eastern art fairs: you don’t commission a cinematic provocateur like Caveh Zahedi to make a film about ‘art as a subversive act’ if you can’t handle the consequences,” I wrote.) After reading that post, Powers sent me an email, one in which he outlined his position that the film was “reckless.” Although he certainly conveyed his low opinion of the quality of the film, the thrust of the email was to urge me to especially consider “the cultural context of the region” and the film’s possible severe repercussions on its participants, some of whom were filmed secretly and without releases. (That email, along with the others relevant to this story, is printed below with Powers’ permission.)

Having traveled to and actually worked in the region, I know the kinds of concerns Powers was referencing. I surprised by the email, though. I didn’t view it as an attempt at censorship, but it was a strong statement to arrive unsolicited in my in-box prior to the film’s premiere. In addition to the other journalists, who include Kohn, Powers also wrote to SXSW Film Producer Janet Pierson, stating that he was “appalled and frightened” by the film and that she had “put [herself] in a difficult position” by programming it.

In an interview this week, I asked Powers, is this something he does all the time — contact festival programmers and journalists about their selections before their premieres? “This is a singular case of me ever doing that,” he said.

There were two other questions I wanted answered. The first: did Powers violate the presumed confidentiality of a submission to the Montclair Film Festival by negatively spreading word about a submitted film he rejected before it had a chance to premiere at another festival? (Powers programs the festival, which boasts Stephen Colbert as a member of its advisory board. Colbert’s participation made Zahedi think the festival could have been a good outlet for his own irreverent movie.) “The film was never officially submitted — there was never a Without a Box application filled out,” Powers told me. “[Zahedi] emailed me on February 26 and said he was going to be screening the film on March 1 and was looking for feedback before [he] locked picture. And that [he] was thinking of submitting it to Montclair.”

The second question concerns Powers’ professional relationship with Rasha Salti, who figures prominently in Zahedi’s movie. As a curator of the Sharjah Biennial, she’s responsible for the commission that brought Zahedi to the United Arab Emirates in the first place. She’s also a programmer alongside Powers at the Toronto Film Festival, a fact that is neither contained within Zahedi’s film nor was acknowledged by Powers in his original email to me. Does Powers think his collegial relationship with Salti influenced his decision to attack The Sheik and I, and does he think he should have acknowledged that relationship up front? “The fact that I know Rasha made me more attuned and sensitive to the issues discussed in the film,” Powers replied simply.

Powers went on to outline in more detail his state of mind: “If I put myself in the position of that time, this came shortly after 35 people had been killed over Koran burnings in Afghanistan. I think that those things are to be taken very seriously. And I do think a festival programmer has an obligation to make some kind of inquiries into the ethics of a film that they’re showing. A festival programmer doesn’t have the tools or abilities to fully vet every film, but I think there’s some light vetting that one needs to do, and that I’ve always tried to do with the films I’ve shown myself. Are there gray areas…? Sure.” He concluded, “I expressed my opinion, and the supreme irony is that Caveh is championing the right for people to express their opinions.”

Countered Zahedi, “Free speech is public speech. [The Powers situation] is all about doing it in secret, and that’s a cabal. It’s trying to control something without people realizing you’re doing it, and that’s not free speech…. It’s one thing to say, ‘Your film sucks.’ It’s another to thing to affect the visibility of a film by approaching [journalists and programmers].”

In our interview, Zahedi likened his situation to that of other artists who have critically confronted Islamic culture in their work. “There’s a war on free speech,” Zahedi says. Referencing the killing of Dutch filmmaker Theo Van Gogh by a Dutch-Moroccan Muslim, Zahedi, who says he’s worried that he himself could face physical attack because of his film, said, “As long as people have this fear there is no freedom of speech and freedom of the press. [Powers] is at the vanguard of the internalization of that fear. We’ve internalized the terrorists. ‘How will they respond if we do this?’ So we don’t do things.”

Zahedi continues, “I think [Powers] really hates my movie, that he thinks it’s a bad thing in the world. But what he’s not seeing is that this is exactly how they win, by us preempting our rights because ‘there could be trouble.’ This liberal programmer is unknowingly and unwittingly a reactionary.”

If Powers’ initial concern was that people could face physical danger due to their participation in the film — a possible outcome mulled over by Kohn in his initial review — he admits now, “With eight months hindsight I’m not aware of anyone being harmed because of this film, and that’s a good thing.” However, there is one thing that he and Zahedi agree on, and that is the publicity value of this controversy. Powers is not unaware of the irony that his emails of last Spring have garnered The Sheik and I publicity on the week of its release. “One of the reasons I was extremely reluctant to say anything publicly is that all the film has going for it is controversy,” Powers said. “And I find it galling that I find myself dragged into the discussion. We are playing into a marketing campaign over a deeply meretricious film.”

Admits Zahedi, “I’m completely using it. But my indignation is real… And the way the film got censored there [in the Middle East] and the way it got censored here are so similar, I had to point it out.” And what of Powers’ claim that his interest was not in marginalizing an artist’s work but protecting the films’ subjects? “One thing that pisses me off is this arrogance [by people like Powers] that they know what this film is, what the costs of the film are going to be, and that they can intervene,” Zahedi continued. “Why does he think he’s entitled to sway public opinion about Sharjah? Weirdly enough, no one in the Muslim world has tried to block my film since the original legal battle. They settled, signed a [paper] saying I have a right to [release] it. The only person who has tried to [censor] it is Thom Powers. It’s weird that that’s where the oppression is.”

Just as I was about to post this piece, I received a second call from Powers as well the text of the original emails to both Zahedi and Pierson. I asked Powers if he has further regrets over the way this story has played out, with the publication of Kohn’s critical piece today and commenters on Twitter viewing this as an example of a gatekeeper using his influence to squelch the fortunes of an independent filmmaker.

“The point I’m sorry has gotten missed,” said Powers, “is that I wanted to focus attention on putting the subjects of your film in harm’s way, and somehow it’s turned into a debate over whether I have too much power in the documentary industry. Caveh has won that battle, but I think the emphasis is [misplaced]. So I may have chosen the wrong strategy. Maybe what I should have done is published this publicly in the first place. But I didn’t think it was my role to take the role of a public critic and write a critique of his film. I did think I was in a unique position to ask writers who are critics to make sure they were considering this film from all the angles. In a way I feel a little bit justified when I read a review like the New York Times review that makes no mention of the safety of the subjects in the film. I think that question was in danger of being lost. And yes, one thing that made me attuned and extra sensitive is that one of those subjects was Rasha, my colleague, who lives in the Middle East.”

Thom Powers’ email to Caveh Zahedi:

Dear Caveh,

Since you asked me for feedback, I want to convey that I watched your film and found it deeply troubling for its breach of filmmaking ethics and reckless behavior toward people who put their faith in you.

The film is framed as championing artistic freedom, but rather than bearing the brunt of risk yourself, you put the greater risk on others – including minors – who could risk deportation, loss of livelihood and potentially worse. Surely you’re aware that 35 people have died in the last week over Koran burnings in Afghanistan. This is a volatile time in a part of the world that you profess to have little knowledge of.

I don’t know if you were feigning naivete about the plight of foreign workers in the UAE when you arrived or if you really were that unaware. It’s dismaying to think a New School teacher would be so clueless of widely reported circumstances in a region where he’s traveling with students.

It’s worse than dismaying to see you recruit foreign workers as performers – and edit them outside of any context they could imagine – in a way that could have dire consequences for them.

Repeatedly in the film we see specialists in the region trying to educate you on how you’re creating dangers for others. But you flout their concerns, treat them like antagonists, and violate their trust by filming them without consent.

No doubt, it was foolish of the Sharjah Art Foundation to assure you of unlimited artistic freedom working in the UAE. But nothing about your account of trying to bite the hand that feeds you comes as a surprise. That story is as old as Hollywood.

You draw a comparison between Salman Rushdie’s experience with “Satanic Verses” and your film. There are big differences. Rushdie was writing about a culture in which he was thoroughly immersed whereas you are not. Rushdie did not mislead people to participate in his project as you have done. Rushdie approached his work with great care and artistry whereas you claim to have arrived in the UAE without a plan and filmed whatever crossed your mind.

My sincere advice is that you should pull the film from SXSW and write it off as a bad experience. This project only stands to bring more heartache – and possibly worse – to you and others.

I’m sorry to deliver such a harsh assessment, but I would rather say it now when there’s still time to change course than to hold back.

Thom Powers

Thom Powers’ email to Janet Pierson:

Dear Janet,

Caveh Zahedi recently asked me for advice about his film. I should say that I don’t know him well. I only had the chance to watch it a couple days ago and was appalled and frightened by what I saw. I think you’ve put yourself in a very difficult position by programming it. When taking such a risk, you’d want to feel assured that the director is someone trustworthy who has the utmost care for his subjects. Caveh has demonstrated himself to be the opposite.

I dearly hope that Caveh changes his mind about showing the film. Below is my letter to him. I’m sorry to throw up such a dark cloud before your festival. But I don’t think this work can be treated lightly. Feel free to call me if you want to discuss further.

Thom

Thom Powers’ email to me:

Scott,

I noticed you listed Sheik & I as a film to watch at SXSW. Caveh shared it with me before the festival and I was taken aback by its reckless disregard for the people he had filmed. I’m frankly worried for the people he took advantage of during filming and I hope you keep that context in mind when writing about the film.

The film is framed as championing artistic freedom, but rather than bearing the brunt of risk himself, Caveh put the greater risk on others – including minors – who could face deportation, loss of livelihood and potentially worse.

Repeatedly in the film we see specialists in the region trying to educate Caveh on how he’s creating dangers for others. But he flouts their concerns, treats them like antagonists, and violates their trust by filming them without consent.

No doubt, it was foolish of the Sharjah Art Foundation to assure Caveh of unlimited artistic freedom working in the UAE. But nothing about his account of trying to bite the hand that feeds him comes as a surprise.

Caveh draws a glib comparison between Salman Rushdie’s experience with “Satanic Verses” and his film. There are big differences. Rushdie was writing about a culture in which he was thoroughly immersed whereas Caveh is not. Rushdie did not mislead people to participate in his project as Caveh has done. Rushdie approached his work with great care and artistry whereas Caveh claims to have arrived in the UAE without a plan and filmed whatever crossed his mind.

In the setting of SXSW, I fear audiences will get cheap thrills from Caveh’s stunts without giving greater consideration to the cultural context of the region that Caveh professes to know nothing about. I hope you’ll keep those issues in perspective.

Best,

Thom