Back to selection

Back to selection

Fatal Journey: Gianfranco Rosi on Fire at Sea

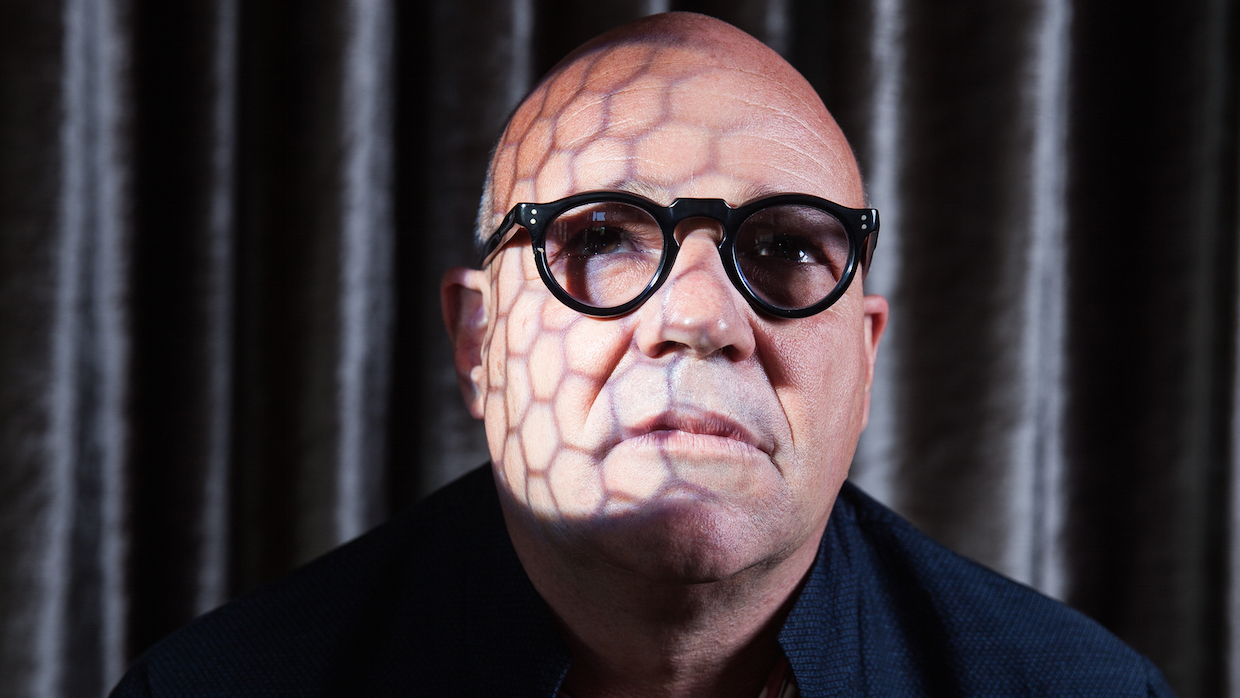

Gianfranco Rosi (Photo by Henny Garfunkel)

Gianfranco Rosi (Photo by Henny Garfunkel) With his last film, 2013’s Sacro GRA, Italian Gianfranco Rosi became the first documentarian to win the Golden Lion at Venice. He was also the first doc director to win the Golden Bear at Berlin with Fire At Sea, a disciplined, urgent look at the migrant crisis anchored on the Sicilian island of Lampedusa, whose proximity to the African coast has made it a target destination for those fleeing their countries. It takes a while before the migrants appear onscreen: initially, Rosi divides his attention among various islanders, including a radio DJ whose tunes are heard all over the island and pre-teen Samuele, who’s expected to follow in the steps of his fisherman father. Blithely unaware of the immigration intake center physically close by but mentally far away, Samuele’s wheezy breathing leads him to an appointment with Dr. Bartolo, the character who links the film’s alternately idyllic and appalling passages.

Bartolo was a family doctor who passed away after the film’s premiere, but he also acted as an on-the-spot first-response physician for the many migrants brought ashore. In a key scene, he shows Rosi photos he’s taken of the dead and dying and explains that, when asked if he’s ever become numb to restoring the malnourished and conducting autopsies on cadavers, he can’t even fathom how that could be possible. The doctor’s humane response leads to the film’s grim apex, where Rosi — who also spent significant time with the marine rescue forces, as discussed below — shows us body after body being unloaded from a failing vessel in an endlessly dismaying stream. The film leaves a mark without using the usual leavening devices — talking heads, graphics giving numbers and statistics, underlining music for emotional emphasis — that would make it merely well-intentioned agitprop; it’s art made under the most grueling of conditions.

A one-man crew, Rosi embeds himself for months among potential subjects before beginning to act as his own DP and sound man. Collaboration with his subjects is essential: a key scene, in which Nigerian migrants chant a harrowing story about their deadly passage, could only have come about from Rosi’s embedded, empathetic methods. To interview him, we asked Roberto Minervini, director of Stop the Pounding Heart and The Other Side — another Italian-born, U.S.-based documentarian who similarly lives wherever he’s filming. As it turns out, the two are intimate friends and spoke for a day and a half at the Toronto International Film Festival. The conversation began with Rosi explaining how he initially conceived of the project.

The Italian submission for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, Fire at Sea will be released this fall by Kino Lorber. — Vadim Rizov

What is happening in Lampedusa? Migrants are arriving and people are living there. What happens to the migrants? They stay two days in Lampedusa. They go somewhere else after. Then who’s bringing them to Lampedusa? The Navy goes back and forth, there’s a boat. So you create an idea of this space — Ireland, Italy, Libya, people arriving, a border, the Navy goes back and forth. We have the fishing boat, the boat searching for migrants and the migrants, so three stories. There’s no more research than this. I had a fantastic experience in New York. I met this sculptor, Louise Bourgeois. Do you know her?

Yeah, of course. At 23, 24, I was starting to make films. I knew someone who knew her very well, and he invited me to visit her studio. It was this huge, huge loft in Brooklyn, and she talked about every single sculpture, every single thing. She has a huge table, full of objects — things she collects, books stacked. She grabs a piece of clay and she says, “I tell you everything started from here, from this piece of clay. Hold it in your hands.” I was like, “It’s a piece of clay.” And then she said, “See, when I started becoming a sculptor, I said, ‘I want to do clay work,’ but I didn’t know what to do or how to transform this clay into something. So I kept this for days in my hand. Then, I finally had some images and something came out. All the emotion was in this piece. My identity of a sculpture is all here.”

For me, that was a lesson, because every time I start a project, I have to metaphorically find this little piece of clay. I spend three months before taking out my camera and trying to understand the place, trying to meet the people. First, they’re people that I have a special relationship with, just like in life. We’ve met, we loved each other, we talk. So I create a special relationship with this kid, the DJ. I was at this party. I see his face, the way he’s playing music — boom. This has to be my film. Then, I am sick on this island, and I don’t know if I want to make this movie. I meet the doctor. We talk about everything. He shows me this little piece of land, where there’s 20 years of his life there. So boom. It was Dr. Bartolo; he became my protagonist.

I meet the grandmother because of the kid, and I meet the father because of the kid. And then, I go to the radio station. I try to film this phone call. Who the fuck is Zia [“Aunt”] Maria every time, calling when I’m fucking filming and destroying my take? Then I have to meet Zia Maria and I’m going to discover another role, you know? Then I meet by chance the fisherman, who goes underwater to catch sea urchins. He’s a crazy man. I love him. Boom. At that point, the 6,000 people of the island disappear. For me, on the island, only these six people live. There’s no doubt anymore that these are going to be my people; I’m going to take them to the end. I never leave them out of the film. Once I decide to film, all the hope and emotion are there, those little bits of clay that I have to then develop. All this material then has to take shape slowly. So it’s been two years, and one and a half years of daily work.

In all your films — and this is the reason why I like your work — you start from the bottom and then the story evolves. It’s more about your experience than a manifesto. The doctor was one of my best friends. I never said to him, “Go eat with Samuele and the family, and let’s see what happens.” Because he will never do that. Samuele was working with me, and that day, he sighs, and I say, “What happened?” “Ah, I can’t breathe.” “You cannot? Did you ever go to a doctor?” He said, “No.” “Dr. Bartolo is a fantastic doctor.” “Yeah, I know about him, but I go to a pediatrician.” “Let’s call him.” And then he talks to the doctor and I have this on the phone. And the doctor tells him, “Well, come to see me tomorrow at the hospital.” That was the first time they see each other, and that scene is so fantastic and true. That’s pure documentary. That’s reality that talks to you. But it’s a reality that has to be transformed into something else, I think. To transform reality into something else constantly, that’s something you do editing and while you’re filming, too: waiting for the right light, the right frame, am I filming handheld or with a tripod?

I decided to film, for the first time in my life, only on the tripod, because I wanted to disappear more. When you breathe, no matter how good you are, there’s still this little movement, there’s someone else. Of course, there is the scene on the boat, which is pure documentary like photojournalism. But there is a scene that is completely handheld at the beginning of the film, where [Samuele’s] looking for the branch. I hated this movement. I had this new, big camera and felt that I’m not steady enough with this camera. So from that day, I decided on a tripod. But that’s good in the film, because it declared that I am the filmmaker watching him for the first time and then we go somewhere else — [to] steady shots, always very, very firm and letting things happen in front of the frame. Every scene has to be completed in one frame. The big challenge is to very rarely cut. You have to find something that has a beginning and an ending. You keep saying, “No, this is not a good beginning. Okay, this is a good beginning. Let’s see where it goes.”

How long are your shots usually? It depends. Sometimes I feel that it is wrong, and I stop immediately and pretend that I’m filming, but I never say to the person, “I’m not filming.” They keep moving in their own life, and then I try to find a different frame, go there, and then start filming again. Once I’m happy I got the truth, for me the scene is done and I move somewhere else.

Okay. So this film has been such a big catalyst for this debate over immigration in Europe — it almost seems that the film marks “year zero” for the immigration problem. For 20 years it’s been like that. After a big tragedy in 2013, where 500 people died a few hundred meters from the island, the Italian government decided to create this imaginary line and moved the border from Lampedusa into the middle of the Mediterranean Sea. A boat from Libya is intercepted in the middle of the sea, by this patrolling boat that goes back and forth, and there are many boats from the Navy, maybe like, 10, 15, which they call the rescue team. When there’s someone in need of help, they have to save them. In the hope of leaving, in desperation, the migrants are arriving to touch freedom, but so many people die on this journey. Before, when they arrived in Lampedusa, there was interaction between the islanders and the migrants. That doesn’t happen anymore, because this boat is intercepted in the middle of the sea. They’re brought to Lampedusa, usually at night. They are in the port. There’s a bus. Dr. Bartolo visits them in the port, very fast, unless there’s an emergency. And then, they take the bus and they go to the center. In the center, they get identified, searched, have their first picture taken, are given clothes. They sleep one or two nights there. Then, they are taken to Italy, where another journey starts in order to have the status of political refugee. And if you don’t get that status, they’re sent back to the place where they come from, which is a very complicated thing.

I want, in this film, to underline even more the fact that these two worlds never meet and never interact. They barely touch each other, without ever having an exchange, even on the island itself. Lampedusa for me is almost a metaphor for what’s happening in Europe. There are these two worlds that cannot get together and exchange things. That’s what I say when people ask me, why is there this separation between these people? There’s literally a very strong separation between these two worlds. I wanted to underline that in the film. As a filmmaker, it was very frustrating because time is my only tool. Time allows me to get to know people, to get involved in their life and be able to film that. With the migrants, I never had that chance. I filmed them like aliens, a group of people that move without individuals, an organic mass that moves in a place they’re not allowed to be a part of. And so, the film reflects exactly the status of things these days. There’s the exception of one scene in the film, which is the chanting of the Nigerian people. For me, when I shot that scene, it was everything because that scene is exactly the truth of a journey. It’s like an epic —

Exodus. Exodus. I witnessed history being told live. Once I filmed that, I felt like I didn’t need anything else, it wouldn’t have that strong sense of desperation and that sense of narrative and truth. A big chunk of what I needed was all in that story. I was able to do that with this little group of Nigerians because I was in a coast guard boat. It was night, horrible conditions — I could not even film how bad it was. There were maybe 50 of them. And then, we arrived in the port. They recognized that I was in the boat with them and really opened themselves to me. The next day, I went to see them again and they said, “Oh, come, we go to our room and we pray. We want you to be part of this thanking that we are going to do in our room.” It was completely dark. And I put down the camera and they started this incredible chant, which is between gospel and blues. And the journey is all there: from Africa to the desert to Libya, prison, they’re drinking urine on the boat, fear of the sea, we cannot die in the sea, now we are reaching freedom and arriving in Lampedusa, where finally there’s the hope of freedom. We in Europe betrayed that hope, and that’s another film: the desperation for people starts here.

The way I work, I don’t ask questions, I don’t interview people. Either I have an interaction that is real, and then I can feel the moment, or I can’t. I don’t go in front of people and ask questions. My teacher used to say to me, “You asked them a question, yet the answer is not interesting. You have to be able to grab something much deeper inside and you don’t do that through asking questions,” which is true.

It’s interesting. Who was your teacher? Boris Frumin at NYU.

Mine was Pennebaker. The first day of class, I asked him why he didn’t do interviews. He snapped, he got angry: “Why don’t you do it?” Chris Hegedus whispered for him to calm down. And she answered for him: “What Donn Alan is trying to say is that the interview is a top down approach.” That was my first day of class in my Masters in Media Studies, and I was ashamed. I didn’t mean that I liked interviews; I just wanted to know. But their passionate reaction of anger made me understand. Yeah, my teacher was like, “You ask a question, you have to answer it. You have five questions, you have five answers. You have 20 questions, you have 20 answers. It’s not interesting.” Also, we have to also understand one thing, that the main protagonist of an event does not always have to be in the foreground. The protagonist can be in the background but it’s stronger on an emotional level. My film is partly on migrants, but also mainly on an island where migrants pass by. That’s what the film is about, and I didn’t invent that. It would’ve been so easy for me to — every day, there’s at least 10 arrivals into the port. There’s a hospital, there is an emergency every day there. I could’ve taken a migrant on the top of the hill, looking at the world that he doesn’t know and having him interact somehow with that. But I would’ve manipulated his reality because he would, in his life, never encounter one of these situations. So my duty as a documentarian was to respect his world. Ethically, I couldn’t take him.

Or you could’ve taken some of the immigrants and dug deeper into their stories, which some people want. But you have to ask more questions, but does this allow me to build an interaction? The only time I was able to build an interaction was being able to witness this scene of the chanting because they asked me into the world. They said, “Come with us. You were there yesterday, saving us in the boat. And now, we want to give you a thank you.” Someone said, “I would like to know more about the people in the Navy boat. What do they do when they do the rescue? How do they feel after?” That would be a different film.

Yeah, and I think also there’s this tendency of wanting to empathize with the subjects, which is a typical Western way of cleaning their conscience: why don’t you give me the human? Because you’re giving them an issue, this nameless mass, either alive or dead, of Africans which nobody cares about. If you gave them the name and the personal story, then the audience would relate and empathize and clear their conscience. And I think it’s brilliant that you don’t do that and knowing you, I’m sure that you don’t do that because I don’t think you would’ve felt good about it. Unless I had the opportunity of a strong encounter. And then, at the end, I showed death. I encountered death. That was the last scene I was able to film because after that scene I didn’t have any more energy to film. I was planning to go to Africa to film Libya — I had another six months, a year of production. And I didn’t do that. When I started editing, the whole film was built in a very conscious way in order to arrive at this tragedy. The first thing I talked about with my editor was, “Jacopo [Quadri], I want to show this scene. I know it’s very difficult to show death and is it ethical? Is it a moral issue? Do we film that? Do we show that? But this is what I want to do. I want people to know that this is unacceptable. The world has to know this.” When people say, “How dare you show death,” I say, “I had the duty to show death. It’s like being in the Second World War and being in front of the gas chamber and you say you don’t film because it’s too strong.”

I think this film could not exist without the death. The death is an integral part. Not only that, but this film was built to arrive to that. The commander of the ship asked me, “Did you go and see what happened under the boat? There’s more than 50 dead bodies.” I said, “No, I didn’t go down there.” And he said, “Well, you have to go there and film that. And I’m sure that you will do a good job.”

And that’s what you did, right? I forced myself to go down there. I have to go through a small hole.

And dead bodies everywhere? Dead bodies everywhere. I had to sit down. The first thing I did was throw up because of the smell and the lack of air and the smell of feces, pee, vomit, all kind of human bodies. To frame that is horrible, you know, to expose, to think about the frame and light.

That’s incredible. That’s something that changed me. I said, “That’s it. I am doing that, but I am not going to film anymore.” That was the last scene I shot, not because I thought the film was finished, but because I didn’t have the strength anymore to hold the camera after that. I called Jacopo and said, “We have to edit with what we have. I don’t know what we have. There’s not going to be a plan B. There’s a story of a kid. There’s a story of an island. There is a story of the rescue, and somehow, we have to put together all of this. Either I abandon the film or it works the way it is.” And I didn’t know if it was going to work or not.

Jacopo came to Lampedusa. I could not be in Rome editing this film or in a fancy studio. We have to be in the place that I was working. I told him as a joke that it was method editing. He was encountering the kid, the fisherman, the grandmother. In fact, we edited the film in two months. It was very, very fast.

In filming death, the only way for me to recover and go back to work was that I had people working with me. Many times, I had to leave the shoot and recover. It takes me a couple of days and then I go back. But you are on your own, and I don’t know — Well, I had an assistant; he was fantastic. Peppino was a person I met on the island at the beginning. He very slowly became my assistant and guide, and I was able to enter in such an intimate way into these houses. So I became part of this community. But when I was on the military boat, I was alone for 40 days and that was enormous suffering. It was very difficult to get the permit to be in a military boat and film.

Nobody ever asked to see my footage, and I had complete freedom of doing whatever I wanted in this boat. This military boat is like a submarine, basically. You never see the light. You arrive alone and with a camera as a filmmaker, and you have to start interacting with sea people that fight every day against all kinds of nature and things that put their lives at risk. We had a very flat sea, but sometimes there were waves of six or seven meters high. And they have to really put their lives at risk. There’s 80 crew people, plus the commander. I didn’t know that the boat was on the frontline. The last day, they told me there was no way the boat was going to encounter any boat of migrants. They told me there was somehow a test to see how I was behaving in the boat, if they could trust me to film or not. Those 20 days allowed me to enter a very strong connection with all of them. I was eating with the crew, dressed like the blue suit that they have, sleeping with them and talking with the commander. At night, we had this conversation from seven o’clock until midnight, two o’clock in the morning, talking about everything: history, life, poetry, cinema. They have fantastic wine there.

This allowed me the moment I had to take out my camera to film, to not feel ashamed of doing that. I would’ve felt embarrassed in the first two or three days to take my camera and film or horrible things. Once we had this relationship, when I took out my camera, I had the support of all of them: “You need something? Go there, look. Why don’t you go on the boat? Go on this helicopter, shoot on the helicopter.” I filmed the small rescue boat, and then I went into the boat to film what’s happening on the hangar, where all the refugees were. And I spent a lot of time. I was the only one speaking French and English, so I was able to talk and calm them down.

At a certain point, when they understood that there was no hope anymore, that all the men were dead, there’s that scene that everybody’s crying, they’ve been crying for hours. At a certain point, I wanted to witness this with my camera and asked them, “Do you mind if I film?” And they say, “Yes, you can film.” I felt so horrible, to have this thing in front of me and film, but I had to film that moment of desperation.

So how does this process change you? What are the repercussions on you, as both a person and filmmaker? I had nervous breakdowns after the film shoots, especially the last one. I was never able to stop and have [a breakdown] because as soon as I edited the film — did I tell you that I edited in the story of Bartolo 20 days before the [Berlin Film] Festival?

No, I didn’t know. That’s another very important story. When we were editing with Jacopo, I felt that something strong was missing with Bartolo. I was so close to him, and it’s so difficult to film someone that is really, really close to you. There were other scenes there that we put in, and I was never happy because it was not really him. As I said before, the duty for a documentarian is to be as close as possible to the person you’re portraying, no? So, one day I said, “Hey, I need something. I want to do something, but I don’t know what. I don’t know what.” And then, it came back in my mind, the [USB key]. [When we met, he gave me a USB key with footage and said] “Go home, watch this, I’m sure you’ll come back here.”

So I went to his studio where I met him the first day and he had his computer. I said, “One and a half years ago, you are the one that made me come here by giving me this USB here. Now, I want you to give the strength that you gave me to the audience that will watch this. You have to be the one that people will trust in order to make this journey possible, to arrive [and be able] to show death in my film.” He started describing what he was watching from his USB. He had a stroke a few days earlier, so he was not feeling good, but he wanted to do this. I shot this basically 10 days before the festival in Berlin.

It’s always a challenge of how much less can I say, how less information can I give and still make a film that is somehow acceptable? The word “subtraction” for me is fundamental, and transformation — to always transform reality. That’s why for me, lighting is important. The clouds, you know? Sometimes, waiting for something — I hate filming. It’s so painful that I have to film. I find all kind of excuses not to film, especially when you are alone. It’s, “Fuck, you know, today I have to film.” And it’s this kind of anxiety, like the first day of school, that you want to postpone it constantly. So I would say I like filming with clouds. This is a fantastic way of saying, “I wait, tomorrow is my big cloud and I shoot.” And sometimes, we wait for three or four weeks for the right sky.

So tell me a little bit more about your approach. You’re by yourself, with the exception of an assistant. How do you shoot? First, technically, what do you use? I’ve used all kind of cameras from the beginning. I started with 16 millimeter on Boatman and partly with super 16 on Below Sea Level. And then, I could not afford film anymore. I had this Panasonic 101, a little camera with the cassettes. To have the frame I wanted, I put on an anamorphic Panavision lens, which was very cheap. Once you had that in, that’s it. You’re stuck and cannot use the zoom. You cannot use anything. This thing was getting dirtier and dirtier, and I think it was great because it gave a texture to the whole film. I shot El Sicario with that camera. Sacro GRA I shot it with a better Panasonic, and then this film with a fantastic camera, it’s an ARRI AMIRA that can basically shoot in the pitch dark, you know? It’s not so light, but it’s a very good, steady camera.

And how do you do sound? Most of the time, I have a lavalier, and then I shoot and use the camera microphone.

And do you do ambience yourself? You go back to do just sound? Yeah, yeah.

So, you have days where you leave the camera and you just listen. I usually do all the sound at the end of my production because I know exactly what I need. And I’m a bit lazy to do sound every day for this. Mostly, I forget to make a room tone sometimes and I have to go back to places.

So for me, this film can only lose an Academy Award to a documentary about the appearance of God. I don’t think at all about that, you know?

Yes, but what would it mean if you thought about it. And we are not in here for prizes, but what would it mean? You’ve won awards everywhere, but we’re talking America. We’re talking awards that recognize the importance as a piece of work here, and also of you to the community. What would it mean, if you won an Academy Award? You win a prize and then you have to forget about it. You have to transform it into something else, which in my case is more freedom to make my film. It was very difficult. When I was at the beginning of my career, I had to make 100 jobs in order to keep making film. I had to teach. I had to be the cameraman. I had to make dubbing. I had to make advertising. Now, I have the privilege of, for the first time, being able to dedicate two years of my life making one film and not doing anything else. And this is because I had a budget to do that, and to immerse myself completely in this film. Also, it’s a good thing to be paid when you work on something — to be paid as a cameraman, as a sound mixer, as a director, as a producer, because we put in a lot of knowledge and time. When I do it, I give up all my personal life. I give up everything. I am in a place and I spent one and a half years in Lampedusa. I saw my daughter five times in this one and a half years.

So you produced the first films yourself, and this is the second film that you’ve worked with other producers because of a bigger structure. Yeah, but I’m always a producer. On all my other films I did before, except Sacro GRA, we didn’t have any budget. I was making $3,000 somewhere, and then I put it in my film. At the end, I didn’t have an accounting of how much I spent. Every time I had money, I put it in my film, but I never count how much money I spent. It was this moment of madness, where I put my personal money in order to have this film finished. And sometimes [this went on for] two, three, four, five years, except for Sicario, which was very short. It was a three-day shoot and there was no budget. Jacopo Quadri gave me $4,000 to go to Mexico and do the film.

In the credits, Carla Cattani from Instituto Lucce is credited for story. Did Carla bring the project or the idea to you? No, Carla called me after I made Sacro GRA and said, “I think you are the person that can make a film in Lampedusa, not only linked to the tragedy of the events of the migrants, but also the identity of this island and try to understand who it is and who are the people that live in Lampedusa.” We went there with Carla to the island. She was there for one week and then I spent another month there. At the beginning of the project, it was like a 10-minute project. Once I spent a month on my own, I saw it was impossible to make a film of 10 minutes on the island of Lampedusa. I took a lot of notes in a diary of my being in Lampedusa. Then, with [producer] Dario Zonta, we sat down and I went through this process. I don’t like writing very much. For me, writing gives me a lot of anxiety. So I sat with Dario and I start telling him all my experiences in those three weeks, and we wrote a journal with a possible structure, and it was accepted. Then Rai and Arte Cinema came in and it became a bigger project. Like Sacro GRA. I was asked to make a film around [a place], but there was no storyline. The idea was, you should go to that place and film. The Instituto Lucce trusted me living there and spending one and a half years on the island.

Olivier Père [producer, from Arte France Cinema] called me and said, “Let’s meet now.” I was completely unprepared. And I sit down in this bar and I start saying, “Okay, this is Lampedusa. This is Sicily. This is Libya. People arrive here.” It became this incredible structure, where I was sketching things. So then I spoke for an hour about that, and the vision of the three stories. At the end of the conversation, he said, “Well, can I keep this piece of paper?” And then I said, “You can keep it if you give me the money for the film. I don’t need to write anything?” “No, this is enough,” he said. So he took this piece of paper with him. Once the film was finished, he said, “You know, Gianfranco, I saw your film now, and it’s exactly the same as the day we met and has exactly this structure.” It’s something that belongs to you so intimately that you forget about it, but it’s what I was telling you about the piece of clay. It’s all there. You develop everything you forgot about, and then suddenly it’s all there.