Back to selection

Back to selection

“You Are Forced to Look Very Carefully”: DP Alan Jacobsen on Strong Island

Strong Island

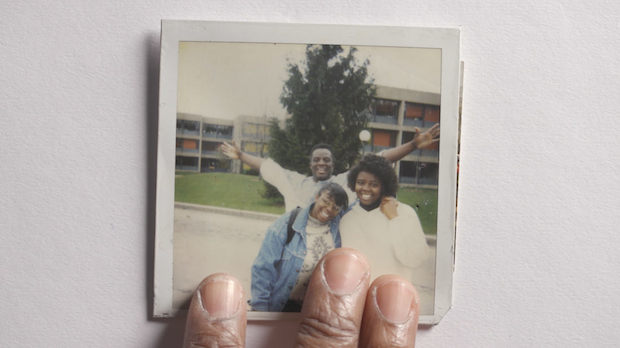

Strong Island Hailed by Filmmaker as one of the 25 New Faces of independent cinema in 2011, Yance Ford makes her feature film debut with Strong Island, an intensely personal documentary on the 1992 death of his brother. Ford worked with DP Alan Jacobsen to create the film’s singular aesthetic, which combines long takes and a camera that never pans or tilts. Ford and Jacobsen drew inspiration from the long take masters, from Tarkovsky to artist Sharon Lockhart. Jacobsen spoke with Filmmaker ahead of Strong Island‘s premiere in the U.S. documentary competition at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival. Below, he touches on the painful nature of this story, the gear used to capture these moments and creating tension through a fixed camera.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the cinematographer of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Jacobsen: Yance reached out to me on the recommendation of filmmaker Marshall Curry, with whom I’d shot two films. I believe Marshall felt that my ability to really dive deep and steadfastly support a director’s vision would be a good match for Yance, who wanted to make a radically unique, intimate film that would use the process and presentation of cinema to explore ideas of loss, grief, bias, and injustice. I was able to leverage my skills of visualization, communication, and collaboration to create, with Yance, a visual lexicon that would serve these ideas, while also working very intimately in some profoundly emotional and intense situations.

Filmmaker: What were your artistic goals on this film, and how did you realize them? How did you want your cinematography to enhance the film’s storytelling and treatment of its characters?

Jacobsen: We wanted to use the camera in ways that would create echoes of experience for the audience. One of the main ideas of the film’s design is that the perspective and view of the camera is controlled and limited in ways that reflect the power structures that confront our subjects. So for example, the camera does not pan or tilt in this film – objects and people might move out of frame and the camera is not allowed to follow. Empty space, unclear or occluded glimpses linger – you are forced to look very carefully, but you don’t get to see everything, you don’t get the whole picture. Alternately, for our interviews, we worked with the visual idea of testimony, or more specifically, missing testimony – that which perhaps would have been given if our subjects had been empowered to give it. The frame is wide, static, straight-on, unblinking. The unbroken length of the shots compel the viewer to really have to look, really listen. To not look away from painful details. There is an unavoidable feeling of control. These and other visual constructs were used to create an emotional immersion for the audience that echo back the themes of the film.

Filmmaker: Were there any specific influences on your cinematography, whether they be other films, or visual art, of photography, or something else?

Jacobsen: For me, I took a lot of inspiration from artists working in long take, particularly Carlos Reygadas, Nikolaus Geyrhalter, and, to an extreme, Sharon Lockhart – whose 50 minute long takes helped justify my 90 second takes. And Yance and I bonded over Patricio Guzmán, Tarkovsky, and Robert Persons’ amazing film General Orders No. 9, again for their ideas about taking the time needed for the audience to really look at deeper meanings. William Eggleston and Steven Shore helped us frame the deceptively peaceful suburbs.

Filmmaker: What were the biggest challenges posed by production to those goals?

Jacobsen: This film was an emotional gauntlet, most obviously for Yance, who was confronting people, systems and history that did not want to be confronted. Day after day, for seven years. Since Yance and I had grown so close, and were often filming alone for long periods of time, it was particularly wrenching to have to keep the camera rolling when Yance was suffering, anguished, overwhelmed. But that tension was key to the truth of the film, and I trust the audience will feel it worth it, if harrowing.

Filmmaker: What camera did you shoot on? Why did you choose the camera that you did? What lenses did you use?

Jacobsen: We shot with a progression of mostly Canon cameras. Very low-light nighttime exteriors where captured with the Canon 5Dmk3 and 1Dmk4 cameras with the fast f1.2 EF primes. Interviews were mostly C300, to allow a similar look but with proper audio and extended run times. Towards the end of production we also used the C300Mk2 at 4K, to allow reframes on the photographs that Yance hand manipulates. All EF lensing, to stay small and intimate. There is a tiny bit of early sony F3/Angenieux and EX3 footage in the film as well.

A key breakthrough on this film was the use of a still photo tripod head – the Gitzo 405 – instead of a fluid head. Using a head that cannot smoothly pan or tilt enforced our desire for a non-accommodating, uncorrected frame – I simply could not wimp out and correct an uncomfortable frame without ruining the (most likely long-take) shot! This was a great discipline to practice, and a fundamental part of the feeling of suspense and suspension in the film. I would try to predict where a person or face or hand might move, and set the frame accordingly. Often I would dial in an empty frame and that hope the action would move into it. The tension that is created around these frames as people move unpredictably, was key.

Filmmaker: Describe your approach to lighting.

Jacobsen: Lighting wise, I am a naturalist. For the most part, the natural, inexorable flow of real natural light is our guide. There is, however, a subtle stylization of the lighting in this film that echoes the idea of testimony. Our interview subjects are lit with a single overhead light, reminding the viewer that these testimonies are, perhaps, a collecting of “evidence” that was never properly done originally. This idea extends further, into a unique light-space we created for Yance’s addresses to the camera. Here, in Yance’s internal “thinking space,” the super tight frame and wrapping light allow us to see black skin in a way not often presented in such proximity.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to realize and why? And how did you do it?

Jacobsen: I can’t describe without spoliers, but you’ll know it when you see it. There were many many scenes.

Filmmaker: Finally, describe the finishing of the film. How much of your look was “baked in” versus realized in the DI?

Jacobsen: Color was finished at Technicolor/Postworks in NY. I was amazed at how well the various 8-bit formats were able to be brought together. Colorist Anthony Raffaele, working on a Baselight, did a fantastic job, particularly on a troublesome interview where the sun was in and out of clouds constantly. I shot in log as much as possible, but we were even able to successfully match a series of direct cuts between ECU closeups shot on C300 and 5D.

- Camera: C300MK 1&2 & 5D MK3

- Lenses: EF zooms 17-55, 24-70, 70-200. EF Primes 50 & 85 at 1.2

- Lighting: Available with tungsten or LED interviews

- Processing: Digital

- Color Grading: Technicolor/Postworks at Baselight