Back to selection

Back to selection

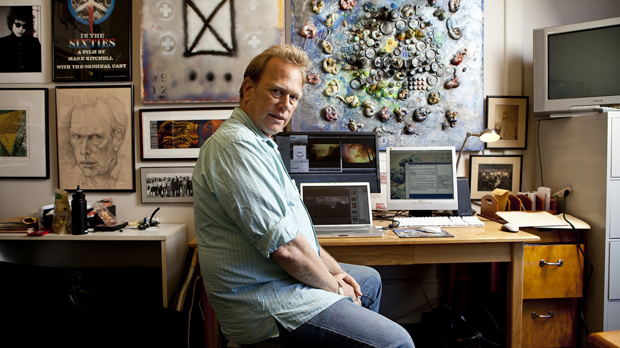

Five Questions with A Fierce Green Fire Director Mark Kitchell

A Fierce Green Fire

A Fierce Green Fire In 1974, Francis Ford Coppola and the cast and crew of The Godfather Part II took over a Lower East Side block in Manhattan. An NYU film student and resident of that block, Mark Kitchell, focused his camera on the proceedings. The result, The Godfather Comes to 6th Street, was not a fluffy “making of” film but a document of the good, the bad and the ugly that happens when a film crew descends on a neighborhood. A portrait of a community, the film also captured the efforts of a group of local activists who objected to the film’s presence; Kitchell had found his themes: community and activism. The Godfather Comes to 6th Street was a festival hit and garnered Kitchell a Student Academy Award nomination.

With Berkeley in the Sixties (1990), Kitchell expanded on his themes. He left the Lower East Side block and embraced a whole city, and went from showing a group of local activists to profiling the birth of the counterculture movement. This historical perspective necessitated a voice-over narrator, a finely researched and written script, sit-down interviews with participants and experts, and extensive use of archival footage. Kitchell efforts earned him another Academy Award nomination, this time for Best Documentary Feature.

Kitchell’s latest film, A Fierce Green Fire: The Battle for a Living Planet (opening in New York City on March 1), tackles a still larger subject, the birth and evolution of the environmental movement. His geographical focus was not a city block or a city, but the planet; the film is, in his words, “A hugely ambitious undertaking.” To help him tell this vast story, Kitchell wrangled some star power to narrate the film, including Robert Redford, Ashley Judd and Meryl Streep.

Filmmaker: A Fierce Green Fire is a history, told in five acts, of the environmental movement from 1960s to the present; that’s a pretty enormous undertaking. Tell me about the process of finding the structure of the film and the challenges of handling such a huge subject.

Kitchell: We started out wanting to do justice to the movement, so we developed a six-part series. But when I went to see Edward O. Wilson, biologist and advisor to the film, he told me, “Mark, you’re never going to get it funded; and if you do, no one will watch it.” He suggested selecting five of the most dramatic and important events and people. We chose them, sitting right there in the bug museum at Harvard. I then built those five main stories out into an hourglass structure for each act. They start wide, with context and origins and then focus in on the main story and character. Then the story opens up again to explore ramifications and evolution of that strand of the movement.

We went through three rounds of production, meaning editing and writing, shaping the film. At each stage we had to face what to leave out. And we kept on adding interviews, so there was more material to deal with. I’m amazed that we got it down to 116 minutes, which was the length for Sundance. Then we went in and took out 15 minutes more. Of course I have regrets about the brilliant and important thoughts that were left out. But we always had the audience in mind and wanted to be sure that the film was as tight and strong, entertaining and informative as possible.

Lastly I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge editors and advisors and all the feedback we got from friends and colleagues. I’m really glad we took the time to do it right.

Filmmaker: The title of the film comes from an epiphany experienced by ecologist Aldo Leopold, when, as a young ranger, he shot a wolf. Did you experience such a moment and know that you had to make films that involved portraying and inspiring activism? Did you experience a Fierce Green Fire with this film in particular?

Kitchell: No I didn’t kill a wolf and see a fierce green fire. I did shoot a moose on a wilderness journey and I have regretted it ever since. My environmental awakening (which is what the Leopold story is about) was simpler, less dramatic. To a certain extent the idea that it is all connected is related to the idea that it’s all one, the revelation some of us were having in the ‘60s. Growing up in San Francisco, California and the West, it’s hard not to take the environmental message to heart. As soon as I saw photovoltaics, I expected that the world would be powered by the sun – it makes so much sense. The decision to make the film was not a revelation that involved activism. If you’ve seen my prior film, Berkeley in the Sixties, that was that epiphany. But I did have a sense of deja vu when I started looking around to see if anyone had made the big picture history of the environmental movement. No one had, so I stepped up. It was my wife’s idea. We developed it together. There were a lot of great books we read, deep discussions. In terms of a fierce green moment, maybe it was Paul Hawken’s Blessed Unrest – the realization that there are two million groups worldwide working on issues of environmental and social justice; and his brilliant metaphor of the movement as humanity’s immune response system.

Filmmaker: The film is a very powerful call-to-action documentary. How do you hope to bring this film and its message to audiences that might not ordinarily watch such films? Are there plans for making it available outside the traditional distribution channels?

Kitchell: We’re doing all the traditional channels of distribution. And the film is catching fire! Up to 60 engagements far between theatrical and non-theatrical. Educational sales and rentals are taking off, too. But where we are really pushing, where our grassroots heart beats strongest, is outreach and engagement with environmental groups and activists. We’re working with big national orgs and local activists. Lois Gibbs’ CHEJ sent out a newsletter to 20,000 followers and now she’s launching a year of organizing around the film. 350.org wants to get the film to 234 colleges that are pushing divestment movements. Marc Weiss, exec producer of the film, just joined the Sierra Club Foundation board and is working on the Obama Climate Legacy Campaign. I’m excited about Beyond Oil, the Sierra Club’s follow-up to their successful Beyond Coal campaign, which stopped 167 out of 180 new coal-fired power plants. I think taking on the oil interests is the main event, a battle of a lifetime. It may take 20 years but we’ve got to get off the carbon kick – and I’m hoping our film plays a role in that campaign. The list of groups we’re working with is long: Green Action, Clean Water Coalition, Maine Natural resources Council, Earthjustice, New Yorkers Against Fracking, NRDC, Friends of the Earth (I’m afraid of leaving people out now, there are so many – Van Jones’ Rebuild the Dream! Amory Lovins’ Rocky Mountain Institute! Bob Bullard…). We’re partnering with them on screenings for now, getting them to speak about their work. Hope to move on to putting on their own events, whether fundraising or educating and organizing. Using the film as a tool for campaigns. All of that… send money, it’s a huge job and we need help…

Filmmaker: The film makes brilliant use of archival footage. What’s the key to finding the right archival images and then using them well?

Kitchell: We had the time to talk to everyone and look at everything. Bullfrog Films opened their library to us. So did The Video Project. I looked at festival lineups and found obscure films. Later on we had people look through the National Archives and UNEP. I found a key film about Love Canal, The Poisoned Dream, while interviewing Lois Gibbs and looking through her library.

We pursued fair use for some sources. The indie filmmakers, our friends and colleagues, we had to treat right. And big archives like ABC and AP we had to license. But we developed something of a royal road to fair use, a way to get around the problem of mastering when you don’t have access to masters. It’s called Dark Energy and deep thanks to Kim Aubry at ZAP for making it available to us – a way to up-rez and correct for motion and frame rate. We did really detailed archival logs and ran them by our attorneys – got everything we wanted. So – hard work and fair use will get you where you want to go.

Filmmaker: You interview a number of activists in A Fierce Green Fire. Did you gain any insight into what attributes they have – the thing or things that motivate them to act – that other less activist-oriented people might lack?

Kitchell: I thought this was a film magazine! No, nothing special. Just the same grit and determination and sense of mission that drives all of us filmmakers…