Back to selection

Back to selection

10 Lessons on Filmmaking from Director Ken Loach

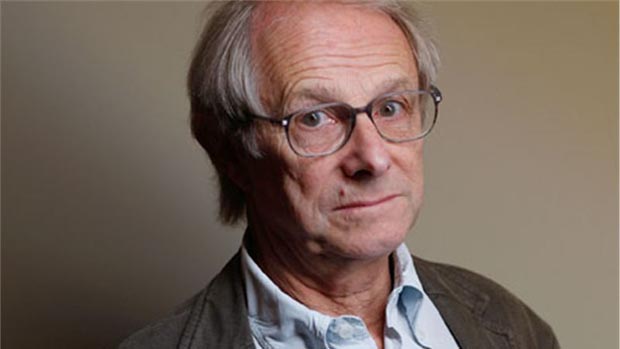

Ken Loach

Ken Loach Few filmmakers bring to life social issues as vividly as Ken Loach. Whether helming grand historical dramas about family, love and civil war (The Wind That Shakes the Barley, Land and Freedom) or character-driven films detailing the plight of the working class (Kes, Riff-Raff, Sweet Sixteen, Bread and Roses) Loach is a master of creating universal stories that are immensely relatable regardless of time or place.

His latest effort, a documentary, The Spirit of ’45, which had its world premiere at this year’s Berlinale, continues the grand tradition with a story as relevant today as it was over half a century ago. The film looks at the sense of hope pervading the U.K. after the Second World War. Its people had won the war together, and believed that they would rebuild their country together.

Loach chronicles the Labour victory of 1945 through the voices of political activists, workers, unionists, and economists of the time. We see the resulting National Health Service and public ownership of utilities and transportation industries as well as what happens to the society after the effects of Thatcherism and the cult of the individual take away these social gains.

Loach succeeds in taking one piece of history and showing how the lessons learned are remarkably important today, as governments around the world struggle to come to terms with balancing the role of the few versus the many.

As a filmmaker, Loach has adopted a working style not unlike that of the characters seen in his films. Unlike the traditional Hollywood model, he’s not driven by his own race to the top, but rather by a collective spirit, a desire to create harmony on the set and to appreciate his crew for a job well done.

He is known for his loyalty, working often with the same team, including producer Rebecca O’Brien and screenwriter Paul Laverty. Filmmaker spoke with Loach in Berlin after the premiere of his film to find out just what else he’s learned in his more than 45 years of filmmaking.

1. Avoid corruption: Find a thrifty team.

I have been lucky. I work with producers who don’t rip people off. And we don’t spend much money, so there are no kinds of silly extravagances. It works mainly because the producers have set things up in a very comfortable way.

I think that, oddly enough, it helps that we’re not spending huge sums of money. It’s a well-paid industry. Even at our level it’s very well-paid. But I think when the sums are huge then it’s very corrupting. So you just try to do the sensible thing.

2. Appreciate the people around you.

I think everybody respects everybody. You try and give them enough time to do their job, and sometimes it’s tight, but we all share the same discomforts.

I think valuing people’s contributions is key. You know if you’re valued, and they are. I mean, I work with brilliant people, and take any one of them away and we couldn’t do it. You don’t have to say it to them. It’s implicit in what you do, isn’t it?

3. The best team is built upon loyalty.

I’ve just been very lucky to find good people, and people have been very loyal, and you try to show loyalty back. And then you develop a common attitude so you don’t have to go over the basics again and again because there’s an understanding between you. It’s just common sense.

It’s such a fragmented industry. I’ve been lucky and have been able to work quite regularly. I think if you can work quite regularly that gives you the confidence to build a team.

4. Cut before you begin. And then cut some more.

You shoot too many scenes that you don’t need. I think that’s one of the biggest mistakes that people could make. And I made that, sometimes at the outset.

We try to cut the budget before we start. We cut the script so that you demand less. Maybe there’ll be a scene, one or two scenes in every film that you find you can do without, but you don’t always know that in advance. But that’s part of the art of filmmaking. And then part of the work is to cut the script before you shoot so that you don’t waste time.

5. Find the epic part of even the smallest story.

That’s in the writing, really. I’ve worked with Paul for quite a long time, and the thing about Paul is that he finds the microcosm, which will tell you about the bigger picture. You see something very small, but through it you know the bigger picture. That’s always what you’re looking for, finding a small story, or a relationship, or a situation, and if you tell that truthfully, you say something about the much bigger picture without actually having to have say it. You infer it, and those are all the stories you’re looking for really.

6. The story should feel effortless, no matter how hard it is to convey.

With directing fiction, certainly for our films, the script is very precise. It’s 98%, what you see on the screen is in the script. One or two percent is added, but it should feel as though it’s improvised. It’s like playing Chopin. You should feel the pianist has just sat down at the piano, and he’s just played this amazing piece just from his head, but of course it was written and it should be the same in the film. It should have all the appearance and quality of just happening spontaneously in front of you, and that’s the trick you have to try and pull off.

7. Edit your script with your enemies in mind.

Part of what you consider carefully all the time is what a film is saying, what’s the subtext of the film and what’s the implication of the film. And is it true and can we justify it and is it open to misinterpretation?

It’s got to be in the script. I found that if there’s a fault in the script, it’s always there at the end. And there have been one or two times where we haven’t got the script quite right, so the faults stay with you, and that’s always the challenge at the beginning.

The secret to having the proper subtext is working on the script. It’s just asking the questions you know your enemies will ask.

8. The writer/director relationship is sacred.

We talk about the story a lot before Paul starts and then he’ll do a first draft. When we’re doing an outline, we’ll talk at every stage, but he does the writing. And when we’re casting, which is a long process, I always like him to come at different times and be there at the end with Rebecca, and then to come as often as possible to the shoot. Often he’ll see something that I’m missing. So it’s a very congenial relationship. You don’t put pressure on each other; you just enjoy each other’s presence, really. He brings the coffee if there’s nothing else to do.

9. And remember, writing and directing are not one and the same.

If you’re a director, remember you’re not a writer. I think a lot of directors coming in now think they have to be the writer as well, and I think that’s the biggest handicap, you know? If you’re a director, you’re not a writer. And if you’re a writer, you’re probably not a director. Remember the distinction.

There are not a lot of good director/writers. Usually the script is too thin. It’s not complex enough, and it’s not deep enough. For a writer who directs, it’s usually too dense. They don’t allow it to breathe.

You need different visions coming in and they’re not the same; they’re complementary. It’s good that there’s another eye on the script and there’s another eye on the directing.

10. Relax.

It’s only a film, you know? Getting up at 6 o’clock on the long days, that’s the biggest challenge. Keeping self-belief is the biggest challenge.

In the end, if you don’t get it right, you don’t get it right, but you’ll still be there tomorrow to learn your lesson.

It’s only a film. Don’t take yourself too seriously.