Back to selection

Back to selection

Susan Seidelman on Smithereens, Fashion Influences and the Early Days of Public Access TV

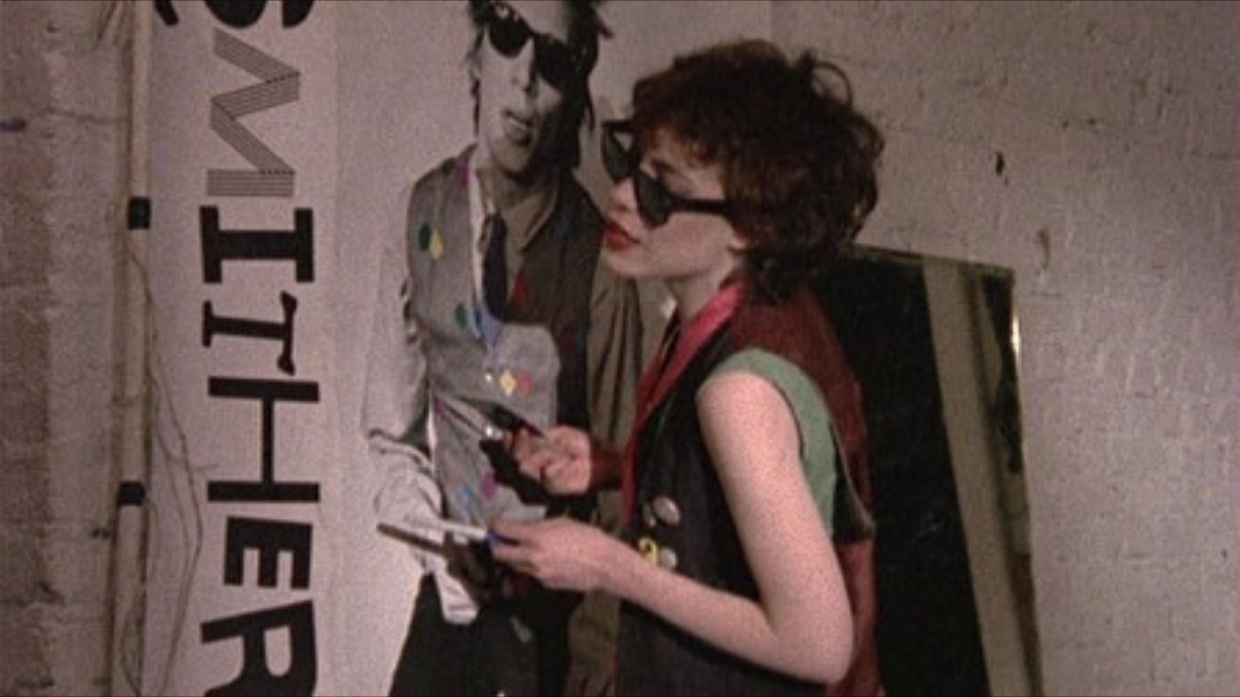

Susan Berman in Smithereens

Susan Berman in Smithereens In the opening shot of Smithereens, a pair of checkered black-and-white sunglasses dangle in the frame. Self-starter Wren (Susan Berman) swoops in, grabs them from the owner and keeps pushing through the subway station as if nothing’s happened. Wren wants to be in a band, but she doesn’t have any discernible abilities besides her fabulously on-point New Wave fashion sense. When not working a crappy copy store job, she’s going to shows and plastering up Xeroxes of a black and white still of herself all over the city, trying to drum up some kind of attention for herself. She only has eyes for Eric (Richard Hell), a narcissistically compelling musician trying to pull together a move to LA, and ignores the advances of smitten, tall-and-handsome midwestern boy Paul (Brad Rijn). They go on a date to a cheesy horror movie but nothing much comes of it — Wren flits relentlessly around down-and-out early ’80s NYC, trying relentlessly to insert herself at the center of a very particular scene. The film is a logical precursor to Seidelman’s follow-up, the higher-profile Desperately Seeking Susan; view these back to back with the pilot for Sex & The City, which Seidelman also directed, and you’d get a quick look at 20 years of change in Manhattan.

Smithereens is a fabulous time capsule, a cheerier cousin to rough contemporaries like Stranger Than Paradise, making the best out of a Manhattan landscape that looks practically bombed out, where nothing seems to matter but music, fast food and cheap beer. (In 2009, Seidelman wrote a piece for Filmmaker reflecting on on the film’s sometimes chaotic production.) An astringent comedy, it’s also a tough-minded sketch of a milieu in which women are expected to be perpetually silent disposable partners for male musicians, and of one woman whose dogged attempts to smash that glass ceiling has her sliding into monomaniacal solipsism. The film will open for a one-week revival at NYC’s Metrograph in a new, fabulous-looking 35mm print.

Filmmaker: I saw Desperately Seeking Susan at MoMA last year, where I think you said there had been trouble with the print of Smithereens — that there was only one copy of it, and it was a difficult restoration process.

Susan Seidelman: I had this 35mm print of Smithereens that was literally sometimes under my bed. Sometimes it was in my closet through hot summers, through cold winters. I never took care of the print, I never even opened the can. BAM wanted to screen it about two years ago. [They asked] if I had a print. I sent it off to them and when they opened the can it smelled like vinegar. They told me the print had pickled — I guess that’s a term they use for when the celluloid starts to disintegrate and gives off this weird odor. They said that they could try to screen it, but they weren’t sure it was screenable anymore. Obviously I was upset, because there might be prints out in some storage bin in LA somewhere, but this is the only print I knew of. I talked to somebody [and] found out that the negative was still at DuArt Film Lab. A woman named Sandra Schulberg has been active in restoring a lot of these movies from the ’70s and ’80s that are just sitting in people’s attics. She got it over to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in LA. They accepted the negative and as a result, they were able to save it and put it in proper temperature controlled environment. They then made this new 35mm print that’s going to be shown at the Metrograph. I’ve been told it looks great, but I have yet to see it.

Filmmaker: One of the things that struck me was the TV’s in the background. Sometimes they’re showing bombs going off or Bedtime For Bonzo. Praise the Lord is in there as well.

Seidelman: You’ll notice that there are a lot of scenes like the one where Wren wakes up in bed sandwiched in between two guys and there is a mysterious blonde just sitting there watching them. On the TV are Jim Bakker and Tammy Faye Bakker. I think they both passed away now but they also ended up in jail. It was the opposite end of the culture that I was showing on screen. The contrast between the two was an interesting statement about the extremes of American culture, and phoniness, and hypocrisy, and delusional looks at contemporary life. The TV is on a lot just as a silent observer of all the activity in the film.

Filmmaker: Did you actually on your own personal leisure time, watch Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker, or was that just something that you wanted to include in the film?

Seidelman: No. At that time, there was a lot very fringe, extreme right and extreme left programming going on. I don’t think anyone was monitoring. It wasn’t big corporations, this is even pre-HBO — ’78, ’79. There was just fringe groups and people putting this programming on. On the one hand there was the religious Praise the Lord kind of stuff, and on the other hand I remember watching naked talk shows. The Robin Byrd Show — she would do a nude interview show. To me the authenticity and the rawness of that stuff was very interesting, especially at a time before cable got to be so corporate and so big. It was public access.

Filmmaker: The Feelies are legendarily reluctant to license their music for just about anything. Was it difficult at the time to get their music for this film?

Seidelman: Actually it was easy because I casually knew Jonathan Demme. He was a friend of a friend of mine, a guy named Ron Nyswaner who went on to write a lot of movies [who] had also written a movie for Jonathan. I had asked as him as a favor to come and watch a rough cut of the film before I had any of The Feelies’ music. He watched it and he knew them, because he was a great music lover. He put me in touch with them. They came to my apartment and saw the film. They had an album that was — I don’t know if it was released yet, or it was just the tapes and it was about to be released. The energy of that music was just so great for this film, as well as for the character of Wren. She’s somebody who’s always on the move, always a little agitated, always going after the next thing. That driving beat just seemed to represent the color of her personality. They allowed me pretty much carte blanche of the music that they had available. Rather than having a composer compose the music to the picture, I recut the picture for their music because I loved their music. Also, I couldn’t afford somebody to actually score the picture.

Filmmaker: The horror movie that they go to see at the St. Marks Theatre has prosthetics or really cheap makeup in there. How was shooting that part of it for you?

Seidelman: I grew up watching the late, late, late show. They’d have a succession of these cheesy horror movies, usually introduced by a guy in a Dracula costume and makeup. That was very much a part of my childhood. On the other hand, once I decided that I wanted to be a filmmaker, and I went to film school, I started watching Godard movies, and Truffaut, and Bergman. I had a love of European art cinema. To me, I wanted to combine that with this love of growing up watching cheesy movies on television, eating junk food. I’m in part a product of that early ’60s/’70s suburban culture. My mother didn’t really cook because she thought canned food and TV dinners were modern. We grew up with all the conveniences of modern, suburban life like Swanson’s TV dinners. Loving cheesy horror movies, I thought it would be fun for the characters to go to one. I thought it would be fun to have the opportunity to make my own. The guy who did the prosthetics was a guy named Ed French, who went on to do other and better prosthetics than that.

Filmmaker: Can you tell me a little bit about shooting at the Peppermint Lounge? It had been a venue at different spots for a long time.

Seidelman: For a short period of time it became this weird, punk spot with a little bit of a performance art overlay. I remember when I went there in 1979, 1980, they had trapeze nets over the dance floor where people were doing trapeze stuff above where the bands were playing. I don’t think it lasted that long, but before some of the other new wave punk or new wave clubs — of course there was CBGB’s and Max’s Kansas City, but they were smaller venues and they weren’t really dance venues. Danceteria came along a few years later, which transformed what the Peppermint Lounge was trying to do, but took it to the next level and made it very popular. That was around ’82 or ’83. The Peppermint Lounge was a transitional club into what would later be the really popular dance clubs of the mid 80s.

Filmmaker: Do you want to talk a little bit about the opening shot, these fabulous black and white glasses that are just dangling? It immediately sets the entire aesthetic of the movie.

Seidelman: Originally before I got involved in film I thought I wanted to be a fashion designer. I had an interest in fashion and graphic design, then realized that I wanted the fashions and graphics to move, and I loved music. A combination of those things led me into wanting to go to film school and become a filmmaker. Patricia Field. who went on to become a big costume designer, especially for Sex and the City, had a punk clothing store on East 8th Street at the time. It was one of the early clothing boutiques that really tapped into that late ’70s aesthetic. I was working with a woman named Alison Lances, who was an aspiring costume designer; she saw the glasses there. When I saw the glasses, we decided that it might be a very interesting way to start the movie, especially if Wren was wearing something that, when you saw the two of them together, you instantly knew why she had to steal those glasses. You didn’t have to explain it in dialogue, you didn’t have to tell much in words about who this character was.

Filmmaker: Who were the fashion designers you were influenced by when you starting getting into that?

Seidelman: I was a young girl during that whole British Mod period. Designers like Betsey Johnson were influential. That whole mid-’60s, British Mod design period was really interesting to me. I remember the first time going to London was on a school trip in the late ’60s, early ’70s, and going to a department store called Biba. There was another line called Paraphernalia, which was all these really interesting British designers that pulled from pop culture. Their clothing really reflected something about the spirit of that time. Another person that came about at that time was Malcolm McLaren. I think he worked with Betsey Johnson. It was all that Mod British stuff that then turned into the punk stuff.

Filmmaker: One of the things that made me laugh really hard in the movie is the kind of detail that I wasn’t sure if it was written in the script or if somebody had thought of it, when Richard Hell opens up his fridge. There are two slices of pizza and they’re just resting on the different racks in his fridge.

Seidelman: I don’t know if it was in the script or not. I can’t say whether it was me or Richard. All that attention to those minor details are what tells you stuff about the characters. Not just the two pieces of pizza in the fridge, but also the fact that he sticks them in a toaster oven in the most natural way — that’s how everyone would warm up pizza. Those are the kind of details that I think tell you a lot about the character. Just like the checkered sunglasses, or Richard Hell nonchalantly pouring beer in his hand and rubbing it through his hair as a hair product.

Filmmaker: You edited this yourself over the course of production. It’s also the last movie of yours that you edited. Do you miss doing that, or did you just do it because you couldn’t afford to pay someone else?

Seidelman: I couldn’t afford anyone and I was coming out of NYU film school, where you always edited your own films. That felt natural to me. Sometimes I do miss being my own editor, and certainly when I work on other things I sit next to the editor. I’m not somebody who walks away and says: “Show me a cut a couple of times a week.” I’m in the editing room pretty much almost full time. Some things you do out of necessity and then you realize that that’s part of the aesthetic of the piece, whether it’s producing it, editing it, editing in the music. A lot of things that now even indie filmmakers who are working on a low-budget level still get other people in to do was sort of natural for a filmmaker to do back in the early ’80s. There wasn’t such a division of labor as there seems to be today. I’ve taught at NYU film school for a number of years, and the kids, even when they’re doing short films, I’m always surprised that they go out and use another person to edit their material. That just wasn’t heard of when I was starting out.