Back to selection

Back to selection

The Best VR of 2016: Arnaud Colinart and Amaury La Burthe on Notes on Blindness: Into Darkness

Notes on Blindess

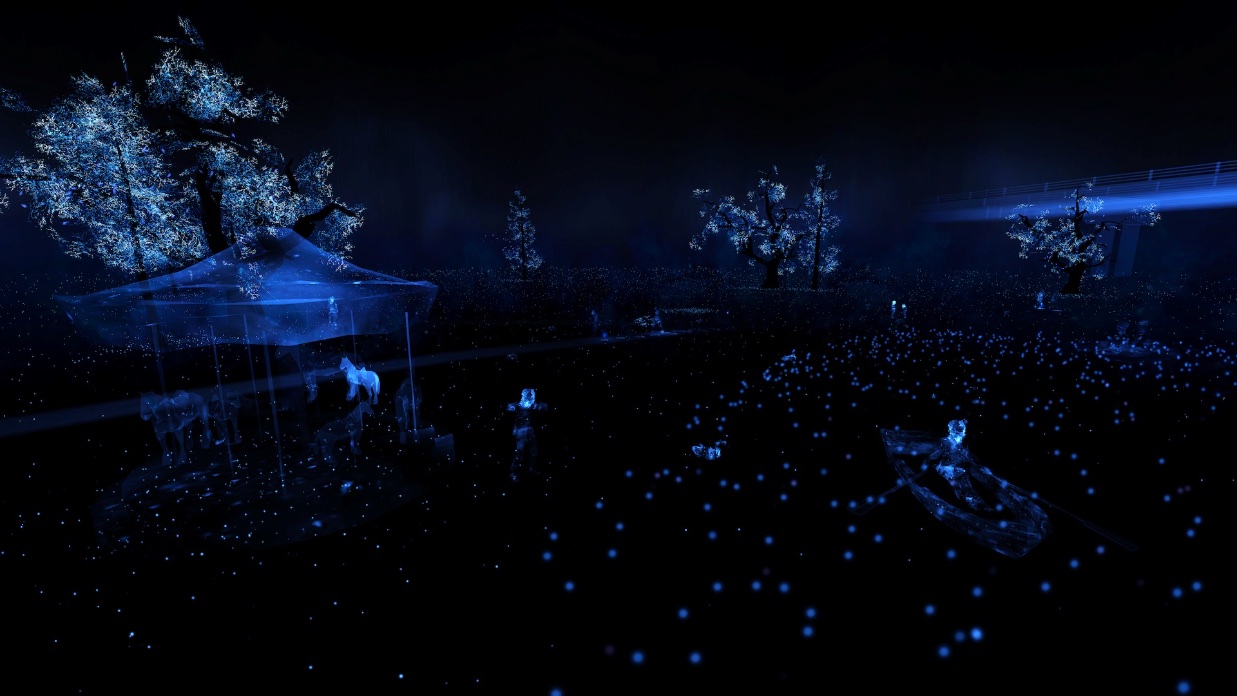

Notes on Blindess This year’s DOK Neuland, DOK Leipzig’s interactive component (housed in what resembled an intergalactic pop-up tent in the beautiful, wide open Markt) allowed me a second chance to experience what will surely go down as the best work of virtual reality seen widely in 2016. Fortuitously, I’d been able to catch Notes on Blindness: Into Darkness — the accolade garnering (Storyscapes Award at the Tribeca Film Festival, the Alternate Realities VR Award at Sheffield Doc/Fest) VR companion piece to Peter Middleton and James Spinney’s much heralded documentary — at the charming Savannah Film Festival’s VR Showcase just the week before. (The doc itself opened at Film Forum in November.) Though it’s now available for free on various platforms, the experience of putting on a headset and virtually falling once again into a “world beyond sight” nearly brought me to tears. And how often does that kind of emotional connection happen with virtual reality? Notes on Blindness: Into Darkness is an astounding work of immersive cinema. Arthouse VR.

The piece consists of six sublime, heartbreaking chapters (“How does it feel to be blind,” “Feeling the Wind,” “On Panic,” “Cognition is Beautiful,” “The Choir” and “Epilogue”), the participant guided by the actual voice of John Hull, a writer who in 1983 began keeping an audio diary to document his going blind (and to keep himself from losing hope). After three years and 16 hours of material, Hull eventually published the diaries in 1990 — prompting the always-profound Oliver Sacks to hail them as “The most precise, deep and beautiful account of blindness I have ever read.” As Hull himself summarizes in the epilogue’s voiceover, “Being human is not seeing — it’s loving.”

To create Notes on Blindness: Into Darkness a pair of French media-makers, Arnaud Colinart and Amaury La Burthe, joined the U.K. team of Middleton and Spinney. Filmmaker was fortunate enough to catch up with the Paris-based duo soon after the documentary’s NYC premiere.

Filmmaker: So why create an accompanying VR piece in the first place — when the critically acclaimed documentary can obviously stand on its own?

Colinart and La Burthe: It was a lot based on a strong commitment from Arte, the French-German TV channel. For many years now they have been supporting the exploration of new media forms. When Arte decided to finance the feature documentary produced by the British company Archer’s Mark (after having seen the Notes on Blindness 10-minute short), they also decided they would very much like to have an interactive component. But not just a simple digital companion — they wanted a real digital experience.

We had just finished working with AgatFilms/Ex Nihilo and Arte on another project called Type:Rider, and everybody was happy with the end result. Both AgatFilms/Ex Nihilo and Arte also knew about our interactive “savoir-faire” regarding programming, but also game design. AgatFilms was also the co-producer of the feature film, so we started working together on a digital project that could exist alongside the Notes on Blindness feature.

We initially thought about an interactive audio podcast based on John Hull’s recordings. And we started prototyping with that. But very quickly we realized we were missing something. John’s work is about bringing sighted and unsighted communities closer, if not together. And the fact that there was nothing to see was a (problematic) showstopper for the sighted audience. So we decided very quickly to add visuals based on John’s description. The question we asked ourselves was, “How does John’s brain actually interpret the sounds he hears?” The answer we found is really an artistic metaphor, and is not based on real brain activity medical research. We also looked a lot at arts around synesthesia (seeing colors and shapes when hearing things).

Thanks to the continuous support of Arte we’ve been able to see and work on the digital part as a different project, but sharing common views and material. We considered the project as a way to raise awareness about disabilities in the sighted audience, one of the core elements of Hull’s work. Peter and James, the feature directors and co-creative directors of the VR project, also were very supportive and helpful with sharing their initial findings in John’s large testimony.

Filmmaker: How is this virtual reality project similar to/different from the doc?

Colinart and La Burthe: I would say that what guided the VR project is really the notion of “experiencing.” This is why we start the experience with this very simple, already seen question of “How does it feel to be blind?” John’s answer is that it is really not a single bit like closing the eyes. It is an immersion in a completely different world of perception. And that’s what guided our work. The doc is really about empathy, learning about John’s journey into blindness and what changed in him. In the VR project we try to bring the emotions and sensations he went through. We do not try to make you feel you are John Hull, but more to experience fragments of what he went through. His voice is there, as a companion, to guide you through this emotional journey.

Filmmaker: With 16 hours of audio recordings, how did you decide which portions of Hull’s diary to use?

La Burthe: It was a long process, but it was entirely guided by the sound. We started by isolating moments and description where we thought we could build an interesting sound world. Because at the beginning we thought about not using images, we had to find moments where we could create very rich, meaningful soundscapes.

I come from an interactive audio background, and I spent quite some time creating interactive, realistic audio worlds. So I really used this experience to find 25 or 30 different extracts where we thought there was potential. Together with Arnaud we selected the moments we thought would best fit the story and let us construct a complete narrative arc, from initially losing sight to the final acceptance of becoming blind.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult part of the production process?

Colinart and La Burthe: Most probably fitting the experience on a mobile device. Notes on Blindness is a real-time interactive experience. It is not a CGI film. Everything is computed in real time and is adapting to your behavior, which is quite a challenge on a mobile device. VR was (and is still a bit) emergent on mobile devices, so the development tools were not stable. We had to custom program lots of things ourselves.

For example, we had to create our own rendering algorithms to get the visual aspects we had in mind. We also have dynamic sound mixing strategies, as well as focus effects and so on. We also had to work a lot on performances. In the first chapter for example, you end up with around 40 to 50 individual sounds composing the soundscape, all binaurally rendered in real-time, which is quite a heavy burden for a mobile phone. We had to adopt smart strategies to minimize the binaural rendering time for some low priority sounds, and we also relied on optimized binaural libraries.