Back to selection

Back to selection

Rise of the Machines: Cathy O’Neil and James Schamus on How Algorithms are Changing Society — and Filmmaking

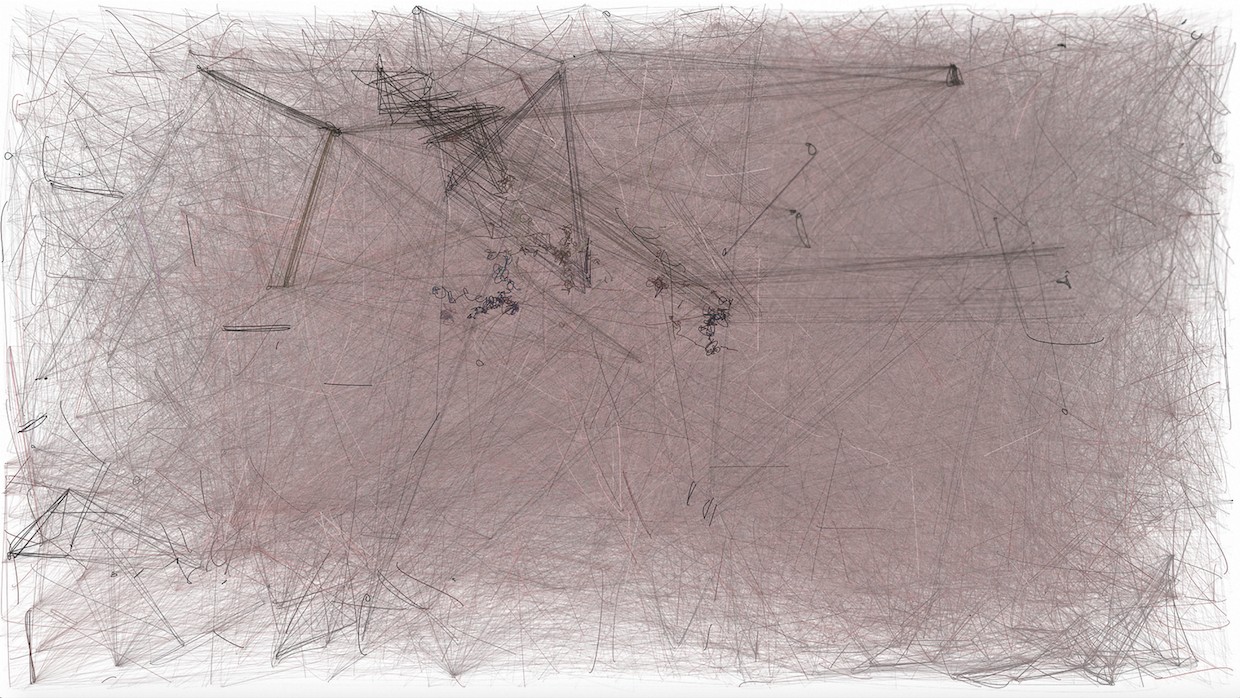

Image: Benjamin Grosser

Image: Benjamin Grosser Amazon and Netflix are having a huge impact on the independent film business, and there are more players entering the subscription VOD space every day, both here in the United States and worldwide. I myself just had a great experience working with Netflix on Kitty Green’s Casting JonBenet, which Green, Filmmaker’s own editor-in-chief Scott Macaulay and I produced. Opening day on Netflix was, though, a bit unsettling. The data driving the film’s marketing, and the measures for its success or failure, are closely held corporate secrets — even the sources and kinds of data the company uses to determine how and when to make the presence of the film on the service known, and to which of its users, are secret. The whole experience was mediated for us, mainly, through our phones — primarily through our Twitter feeds, on which, seemingly within minutes of the film’s global launch, came a roaring wave of robust and spirited appreciations as well as the usual 140-character bomb tosses. But the more transparent markers of success or failure — box office and ratings, which connote number of viewers and from which one projected the default waterfall through ancillary media like home video and pay TV — are unavailable to those outside the corporate gates. Even within the company, it appears, viewership numbers and their uses are closely guarded and filtered. This means that the usual metrics with which content creators previously determined their value in and to the system — from the calculation of residuals by unions and guilds to the sharing of profits by filmmakers — have been supplanted by the neverendingly refined algorithms used by these companies to help shape (and sometimes replace) their decision-making processes. And, when it comes to these new streaming services, what we mean by the “system” is itself hardly understood by most filmmakers because the ultimate value of what we produce is now dependent on the value of the data produced by users’ interactions with our work, and the uses to which those data are put to monetize and make actionable the surveillance to which we and our viewers submit in order to be part of this new culture.

To start a discussion that might make sense of this experience, I thought it would be great to introduce Filmmaker’s readers to someone who may not have much of an acquaintance with the ins and outs of the independent film business but who knows a lot about the economics and politics of algorithmic culture. Cathy O’Neil holds a doctorate in mathematics from Harvard and has taught at MIT and Barnard, worked at hedge fund D.E. Shaw, and, since her resignation from that firm, has become a leading radical voice bringing mathematical literacy to public discussion of the ways corporations and governments are using data and “dataveillance.” You can follow her work at https://mathbabe.org; her recent book, Weapons of Math Destruction, is a fantastic introduction to the ways in which Big Data and its attendant ideologies, as used by banks, credit rating agencies, school districts, police departments and others, reproduces inequalities and injustices in ways most of us are only vaguely aware of.

Filmmaker: Twenty-five years ago, all of us independent filmmakers thought, “Oh, fantastic, there’s this new thing called cable TV, and there will be 5,000 channels and narrowcasting, so that if anybody is interested in low-budget coming-of-age movies, like the one I just made, there’ll be a whole channel for them, and then we’ll all make money.” Then we started hearing about this thing called the internet, and about the long tail. So it was, “Great, nobody now wants to see my film, but I’ll put my VHS tape up for sale online and over the years it’ll make millions of dollars.” Now we have this new thing, algorithms, through which our audiences will be targeted precisely. So everything we do will immediately find its way to the fantastic people who are there waiting for it. I often go to panels at film festivals and point out that now, in our business, it’s the people who have the algorithms who have the power. But I actually have no idea what I’m talking about. What am I talking about?

O’Neil: Here’s what you’re talking about. Algorithms are automated tools to decide on the fate of the rest of us. For example, algorithms are now in charge of hiring people. Seventy percent of applicants have to take personality tests to qualify for an interview for a minimum-wage job, and even for white-collar work, HR algorithms filter resumes. In other words, you actually have algorithms deciding whether you’re going to be a fit for a job before a human begins to consider you. Algorithms are also increasingly used to assess people at their jobs.

For that matter, policing has really changed in the age of the algorithm, with police deciding where to go by using “hot-spot policing” or “predictive policing” algorithms. Of course, algorithms decide how much interest we pay for credit cards, and how much our insurance premiums will be, through minute profiling and tons of data.

That brings me to an interesting point. As some industries become more data driven, their business models kind of undermine themselves. Consider insurance. Insurance was invented as a way to pool risk, and pooling risk, in some sense, assumes that you don’t know exactly what the risk is for a given person. But if you end up knowing so much about a person that you can reasonably predict when and how they’re going to get sick, then they’re going to end up paying for their treatment before that might happen or else get thrown out of the system completely. That’s assuming we don’t have rules about pre-existing conditions.

Given that algorithms are everywhere and are deciding our lives, that brings up the question, are these algorithms right? And I maintain that they’re very, very flawed. We should be very suspicious of them. Predictive policing is a perfect example of why we should be suspicious. The idea is they’re going to take in a bunch of crime data and try to predict where the next crime will happen. But, the problem is, we don’t really have crime data. What we have are proxies for crime data, and they’re all terrible. Some cities use arrest data as proxies for crime, and some use reported crime. New York City uses reported crime. Other cities use arrest data. They say, “As a proxy for where the crime is, we’ll look at where people have been arrested for crimes in the past.” The problem, though, is that most crimes never get reported, and most crimes never lead to arrests. So when you’re trying to use the best proxy that you have to actually locate and predict crime, you’re just using a very flawed data set.

And when you’re using that kind of data set with overpoliced neighborhoods to look for future crime, you’re going to end up reinforcing this pattern of overpolicing, so, for example, even though white people use marijuana at higher rates than Blacks or Latinos, 86% of all pot busts in New York this past year were of people of color. That’s a statistical farce.

Filmmaker: In other words, prediction becomes production.

O’Neil: That’s exactly right. It’s a feedback loop, and it automates the status quo. Predictive policing is much more of a police prediction tool then it is a crime prediction tool. Until, of course, some day when the police decide, “Hey, we shouldn’t overpolice this neighborhood and underpolice that neighborhood for, say, pot smoking.” That will be the moment when the prediction tool seems very out of whack because the police are acting differently.

Filmmaker: Reading the chapter of your book on predictive policing, I was struck by the similarities between the way law enforcement uses those models and how digital marketers and so-called recommendation engines might be influencing what movies and TV shows get put in front of us.

O’Neil So, now let’s try to talk about the film industry and the extent to which these problems arise around Big Data. How is the value of a filmmaker’s work adjudicated? What are the data used? What are your bad proxies?

Filmmaker: To answer that we have to tackle the ways in which “following the money” has become nearly impossible for filmmakers over the past decade. If you’re putting down a chunk of change to make a movie, how are you going to get it back and where is it going to come from? And since the rise of television, and the rise of syndicated packaging of films for television, the so-called back end, the ancillary rights we used to think of as following from the initial theatrical distribution window for film, have been in flux. When box office declined in the 1950s with the rise of television, suddenly TV was killing the cinema. And then suddenly TV was saving the cinema because we were all making so much money selling our movies to television. Then VHS tape was going to kill the film business, and then VHS tape saved the film business yet again because the revenues derived from home video equaled, if not exceeded in many ways, the revenues derived from theatrical rentals. When cable came along, it was the same story until Starz and HBO and others turned out to be the biggest buyers after home video for rights to movies, and pay TV back end saved the film business. And now we have the streaming services — though this time the story may well turn out differently. Cannes this year was a very illuminating moment when the digital back end moved to the front of the conversation, but there was an inability to articulate how to even conceive of the value of the theatrical front-end window. So, what we’re dealing with now for filmmakers is an array of “for hire” signs out there, like for all those minimum-wage job applicants, but we have no idea what the algorithms are that are potentially determining our valuation because part of the value of the companies, like Netflix, that are operating these algorithms, lies precisely with the aura around the secrets that they hold. The data are locked away in a black box.

O’Neil: But was that not true when you were selling to HBO?

Filmmaker: Well, you started with box-office grosses — a proxy still for the eventual overall value. And HBO paid a percentage of that box office. With the new services, you don’t have Nielsen ratings, you don’t have box office — you have no information about how big and who makes up your audience.

O’Neil: So, as with predictive policing, it’s a tale of proxies. The proxies used to be imperfect, but they weren’t too bad, either. Someone going to the cinema and paying for a ticket was a real thing. Now, you don’t have that.

Here’s a question. To what extent can you trust that Netflix and Amazon have the right proxies when they’re hiding them from you? Is success a product of the way they’ve designed their site or the way they market a certain movie to a certain demographic? You have no vision into that.

Filmmaker: Yes, on the one hand, it’s not a matter of grosses, as we all know that some eyeballs are more valuable than others for different online content providers. On the other hand, at Netflix at least one aspect of valuation is pretty clear: How much money are they getting from subscribers and is their subscriber base growing? My old pal Ted Hope, with whom I used to run the production company Good Machine, is now over at Amazon on the film side. They are making all these amazing movies and spending all this money, and god bless. But people sometimes ask me, as if I know, which I don’t (laughs), “How do those numbers add up?” My answer is twofold. They don’t, obviously — and they do. They don’t if you think about the numbers as an advance on what the film is worth if you were selling the movie and collecting money from the audience and the advertisers who want to reach that audience. But they do add up if you think of the movies themselves as advertisements. In other words, we used to advertise our films, but in this environment, the films themselves are advertisements for something else. But what is that something else?

O’Neil: Amazon is the poster child for “We’re gonna be losing money for the long term in order to rule the world in the very long term” (laughs). So I feel like paying a lot for certain kinds of movies is just a part of a very long-term plan to own the attention of upwardly mobile, middle-class people who are film enthusiasts.

Filmmaker: That’s that old concept of the loss leader. We saw this with Wal-Mart, which got into the DVD business and undercut traditional vendors because they knew that people who would throw a DVD into their basket on new release day would spend fifteen to twenty percent more on the other stuff in their basket. So, lose a little on the DVD and make it up on the toilet paper. Amazon, you could say, is doing something similar.

Filmmaker: But there’s something profoundly different going on, it seems to me, and perhaps with Netflix, too, over time, and this is where we really get to the crux of the question of what’s the value of our work. The value is that these companies are essentially data surveillance, or dataveillance, operations. The populace watches our work so they can be watched watching it. So, as filmmakers, will we ever have any chance at even understanding the value we bring to the system? For example, you make a brilliant film about a getaway driver, and that driver is super sexy, super cool, and there’s great music, and your name happens to be Edgar Wright. You sell that movie to, say, an Amazon-type company here, or in China, or elsewhere. The people who are actually delivering that film to consumers on that digital platform know some things about their consumers. For example, are you somebody who, last week, searched for the prices of leases for sports cars? If so, they actually know the prices that were quoted to you. They now know that you’ve just watched Baby Driver and that it’s time to service you pitches and appeals that, even if they’re not directly related to the film, have a much higher prospect of success. And these pitches are calibrated to your income level, the type of cars you’re interested in leasing and the fact that you’re very excited about driving fast at this particular moment. And because these companies get data pretty quickly via A/B testing, they know what’s working for all the people who just watched Baby Driver in a similar data environment. The filmmakers, however, will have no idea that this is going on and no idea how much extra income has been generated as a result of calibrating your love of Baby Driver with your interest in leasing a car.

O’Neil: You’re absolutely right. The reason Google makes so much money on advertising has little to do with billboard banner ads. It’s about targeting exactly who these advertisers want to get in front of. But I guess we should be careful what we wish for. The data are so deeply complicated. I’m not sure the data would be interpretable for filmmakers even if they had them.

I know you have a lot of respect for the way they’re thinking about movies at Netflix, but as a person who’s done coding in my life, and who’s written data science algorithms, I know lots of mistakes are made. And I’m sure stupid mistakes are being made now — blind spots. Going back to the predictive policing model, we are simply following our historical noses and guessing that what will work in the future is what worked in the past — predicting the police instead of predicting the crime. An algorithm will never see a blind spot. It takes a human to say, “Hey, this algorithm has a blind spot.” You can’t say that if you don’t understand the algorithm and you don’t question the algorithm.

Filmmaker: And this is where I defend what looks like the silly excesses of the folks at Amazon or at Netflix. Often, at least in this phase, they are saying, “Filmmakers, go. Here’s a lot of money. We’ll never share with you any of the data about even how many people saw your film, or who they were. But go crazy, and we won’t mess with you, because we’re just throwing stuff into the system and letting it happen.” You get reports from the folks who work often with these companies that there’s a creative freedom that they’ve certainly never experienced at the studio or network level. It’s an odd feeling, a feeling I’ve now had the experience of, which is having no idea, really — except that if people are nice to you and want to spend money on your next thing — whether or not a film worked, how it worked or how much it worked. In terms of building careers, too, you have a very interesting “proxy” as you say, for your value as a filmmaker, which is there are a bunch of algorithms out there churning out some approximation of what you might be worth. But you and your agents have no idea what that value is.

O’Neil: Creative freedom sounds great.

Filmmaker: Well, careers are also good — having some sense of the value of your input to the system versus what’s being extracted from it and you.

O’Neil: Last point. Let’s do a thought experiment. A hundred years from now, when there’s only one company and it’s called Amazon (laughs).

Filmmaker: Will Mark Zuckerberg still be president? (laughs)

O’Neil: No, Mark Zuckerberg, uploaded to the cloud after the Singularity, will be president (laughs). Young filmmakers will want to make something, but there’s only one game in town. If they want their film to be a success, they have to sell it to Amazon. How will they possibly know what to do?

Well, again, I actually think that for the system itself to work that it must quite logically preserve a space of uncertainty. It’s not about executives having so much data that they can predict exactly what’s going to happen in the future. It is rather that they have managed a system in which the cost of maintaining a creative class in a state of precariousness without health insurance, without career paths, without residuals, without any kind of job security whatsoever… It will look like a lot of money to filmmakers at the moment when they sign the contract, but they will never know if they’ll be able to do it again or why it happened. Everybody’s a little off kilter, and so the business runs on the energy of vacuuming up all of that stuff and then metabolizing at as extreme a rate as it possibly can to extract the value from it. So no one besides the people sitting inside a very specific part of the company would be able to understand what the actual return was. I think that’s what we’re seeing now.

— It’s kind of the gig economy mindset.

Filmmaker: Absolutely. And you know, we’ll always have independent film — like, “We’re independent!” But there’s a sense in which we want it both ways. We want to be independent, but we also want a sense of fair share, and security, and a transparency in all those things. So I would say the following, which is that the future independent film business may look in many ways a lot like it looks now, but the precariousness of those who are actually doing the creative labor will, if things go the way they’re going, surely continue to increase.

O’Neil: Well, if it’s any consolation, I feel like that will be the case for nearly everyone.

Filmmaker: Correct, including the Lyft or Juno — not Uber! — driver who might have brought us to this meeting (laughs).

O’Neil: And the math professors, who will be adjuncts.

Filmmaker: Well, on that extremely optimistic note, is there any ray of hope from the cloud?

O’Neil: Well, you know, I am actually not that pessimistic. I do think that algorithms will be forced to become more accountable, at least the ones doing things that are already regulated — things like hiring and sentencing. I don’t think that in 20 years an algorithm will be able to be racist or sexist or to deny work to people with mental health problems because it’s an algorithm, which is the current situation.

Filmmaker: We can only pray.

[Image: Benjamin Grosser is a visual artist whose work focuses on the cultural, social and political effects of software. The accompanying artwork is from his series, “Computers Watching Movies,” a computationally-produced work using computer vision algorithms and AI software written by Grosser. The work shows what a computational system sees when it watches the same films we do — and in the case of this temporal sketch, that film is Christopher Nolan’s Inception.]