Back to selection

Back to selection

Canyon Cinema 50, Art of the Real and Emile de Antonio in NYC, Week of 4/27

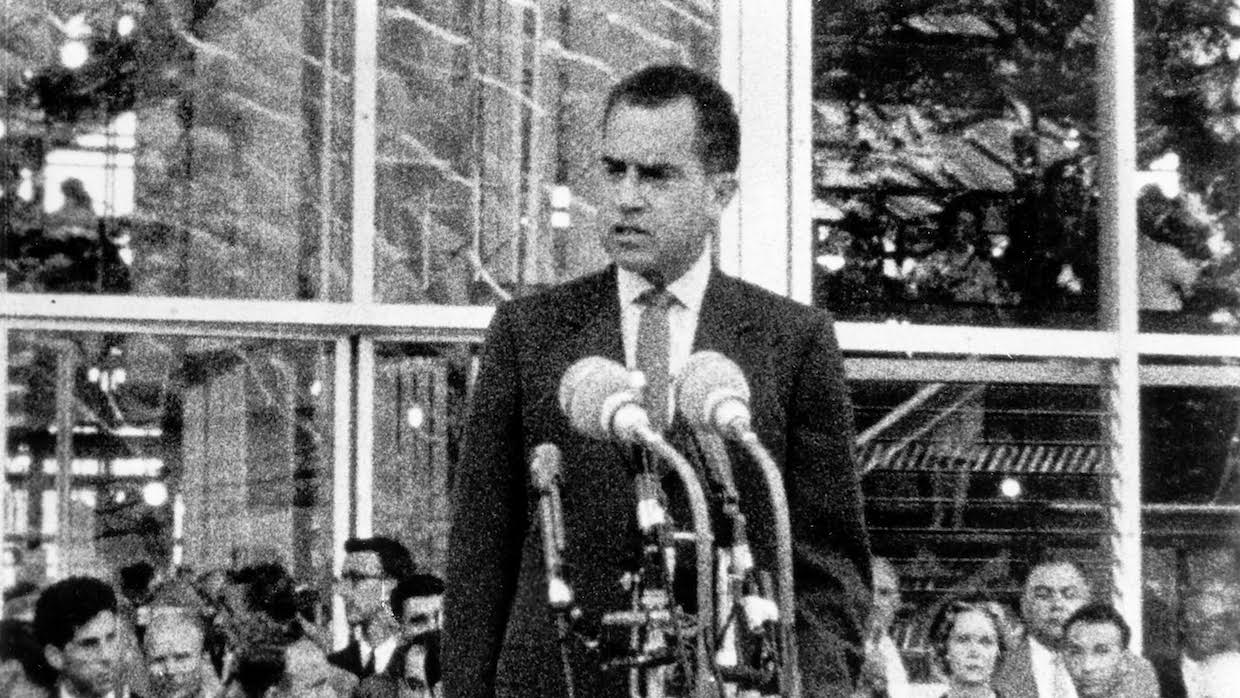

Millhouse: A White Comedy

Millhouse: A White Comedy A few weeks ago my Twitter feed abruptly devolved into a long argument about The Canon: is it just an ossified collection of movies made by white men that should be junked? I don’t think The Canon is a fixed, immutable body of work, never to be added or subtracted to — it’s being constantly reshuffled, with films and filmmakers rising and falling in prominence. Repertory houses have a major part to play in that process, which I note while in the position of wanting to commend a smattering of series and screenings kicking off this weekend in NYC, none of which have anything in common. But as anyone who’s been to a film festival knows, watch enough movies in close proximity to each other and throughlines which don’t actually exist will start emerging; in this case, ideas of canonical intervention and shifting critical reputations come into play.

Curated by David Dinnell, formerly of the Ann Arbor Film Festival, the “Canyon Cinema 50” series kicking off at Anthology Film Archives tomorrow is a four-program dive into the archives of the nonprofit that serves as a repository for much significant experimental work made since 1961. I lack the historical knowledge and viewing to contextualize these films properly (for that, turn to Michael Sicinski), but the two programs I saw at a press screening are both thematically tightly curated and otherwise wide-ranging starter sets to dive into the experimental canon. I had embarrassingly never seen some of the most canonical of the shorts included (Barbara Hammer’s Dyketactics for starters), and now I have, but there’s more to discover besides belatedly checking off boxes.

I don’t meant to demean my personal favorites of these by comparing them to narrative films, as if the experimental can’t lift for itself; still, my mind went there. Emily Richardson’s 2001 Redshift is a time-lapse nighttime horizon film which put me in mind of David Lynch (although after Twin Peaks: The Return, pretty much everything does); the darkest of nights, punctuated with a few crackles of sudden light and some electronic hissing on the soundtrack, complements his patented images quite well. Ostensibly a sort of portrait film, Robert Fulton’s 1970 Starlight is like nothing so much as latter-day Terrence Malick without all the nonsense; the camera swoops as quickly and kinetically as anything in Tree of Life, but the short takes care of business in five minutes. In an alternate universe, this would be more widely known and short-circuit the need for, say, Knight of Cups; a whole mode of filmmaking I thought was at least new and bold turns out to have been definitively charted almost 50 years ago. Greta Snider’s lovably loose 1996 Portland is a shaggy-dog story about a weeklong visit to that city that went terribly wrong, if not life-threateningly so, told by echt-’90s slackers drinking Mickey’s in footage that seems ready-made for cutting into a video for a contemporaneous Matador band. John Smith’s 1975 Associations matches phonemes and syllables with images, reshuffled at dizzying speed, forcing you to connect the links without necessarily adding up to a meaningful syntactical unit; it should be required viewing for linguistics students.

Lincoln Center’s annual Art of the Real series, which kicks off tonight, is composed nearly entirely of recent work; still, the one selection I saw prior to kickoff does kind of engage the canonical question. We’re over a decade out from The Death of Mr. Lazarescu and the general blowing-up of the Romanian New Wave; do people still care? I’ve always been especially partial to the films of Radu Muntean, Cristi Puiu and Corneliu Porumboiu; all formally very different, united by their films’ recurring, bleakly hilarious emphasis on unbelievable rudeness and bureaucratic corruption as constants in Romanian daily life. This is, admittedly, a very particular taste, to which Porumboiu’s latest, Infinite Football, definitely caters. This is ostensibly a portrait of his cousin, a man who has a proposed set of revisions for soccer that would effectively make it a different game entirely — and while the film is sincerely interested in the (de)merits and particulars of his plan, it goes through six or seven distinctly different movements, always finding new and startling forms to take in a very low-key, minimal-resource way. The part that was precisely for me is a sequence in Porumboiu’s cousin’s government office, where he starts detailing how boring his job is and the numerous times he tried to get out of Romania. Director and subject are interrupted by a middle-aged man and his very elderly (92!) neighbor, who are back to pursue a land claim that hasn’t been resolved since the overthrow of Nicolae Ceaușescu. The cousin wants to help, so he calls his colleagues at another office, but of course nobody’s answering — maybe they’re all in a meeting! — and so on and on. I’ve been watching 13 years of these bureaucratic nightmares, and I’m all for it — the first round of reviews for Football following its Berlinale premiere were mixed, but this is a real film, not just a tossed-off sketch.

Is Richard Nixon’s “Checkers speech” canon? As an obsessive Nixon (let’s not say “fan” for obvious reasons but) scholar, I’m truly excited that Metrograph’s Emile de Antonio retrospective will allow me to watch all 30 minutes of the speech in glorious 16mm, paired with de Antonio’s Nixon compilation doc Millhouse, which I have never seen; truly, it’s the Nixon screening to end them all. As it happens, until recently the only de Antonio film I’d seen was Point of Order!, which kicks off the series. If you haven’t seen it, it’s pretty essential: the infamous Army-McCarthy hearings cut down to their historical greatest hits (“at long last sir have you no decency” et al.), a source of great guilty entertainment. I suspect the coming equivalent, if Congress ever gets down to business, will be considerably less articulate or watchable, which is a thought that also crossed my mind while watching a press screening of de Antonio’s In the Year of the Pig. This reasonably well-known 1968 documentary is a sober-minded, meticulously structured series of interviews and archival footage explaining the Vietnam War up to the point of its making from, primarily, the Vietnamese perspective. This is still illuminating and enlightening, even as the interview segments — now completely periodized — lean into a very particular type of cadence and public speaking that doesn’t exist anymore; I was reminded, guiltily, of faux-documentary sequences from early SNL. When the infamous Curtis LeMay appeared onscreen to rant about communism, a terrible thought crossed my mind: compared to the current ostensible president, LeMay sounds downright articulate and borderline acceptable as a policy thinker and human being. I do not envy those to come who must watch or make compilation films about this particular epoch, because it will be nigh unwatchable.