Back to selection

Back to selection

“Must Political Solidarity be Unconditional?”: Rachel Leah Jones and Philippe Bellaïche on Their Sundance Doc, Advocate

Advocate

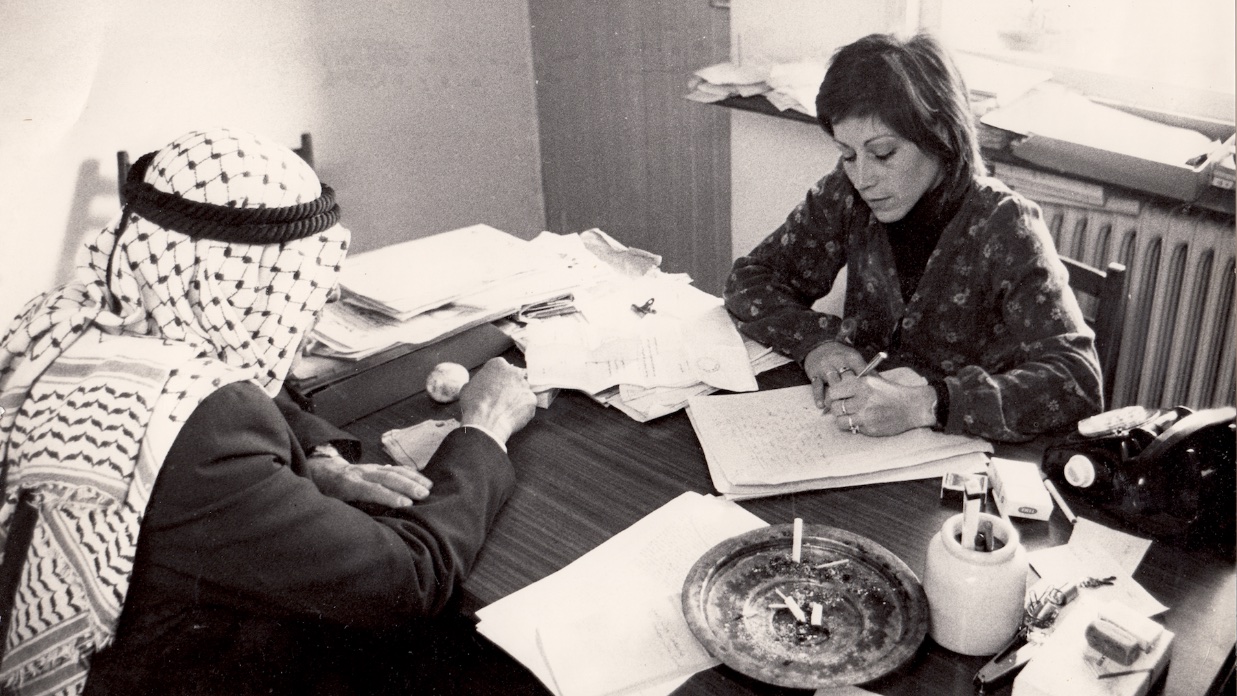

Advocate Long a lightning rod, Lea Tsemel is an idealistic Jewish lawyer who has spent the past five decades defending political prisoners. Or she’s the terrorist’s go-to barrister, rarely turning down a case no matter how heinous the crime. Like most things in Israel, the perspective depends on which side of the occupation you’re on.

Veteran filmmakers Rachel Leah Jones and Philippe Bellaïche understand this reality all too well, having followed Lea Tsemel’s career closely for the past 25 years. And now with their Sundance-premiering Advocate they’ve created an in-the-trenches portrait of this unapologetic firebrand, trailing Tsemel as she juggles high-profile cases (including that of a 13-year-old boy implicated in a random knife attack), while weaving in archival footage of her past legal battles — most of which she loses in Israel’s skewed system. Which is precisely what makes Tsemel such a remarkable character. A warrior for justice who’s spent her entire adult life taking punch after punch, she forever gets up undaunted to fight another day.

Filmmaker spoke with the equally passionate co-directors prior to the doc’s January 27th Park City premiere in Sundance’s World Cinema Documentary Competition.

Filmmaker: I know you encountered Lea decades ago, but how did you meet? And when did you start thinking about making a movie about her?

Jones: I first met Lea over 25 years ago, toward the end of the First Intifada, when I returned to Israel (where I had grown up) to see if I could reconcile my critical adult politics with my Israeli inner-child. It was people like Lea, and her husband Michel, who made it possible for me to bridge the gap. The idea of making a film about Lea was in the air for years, but Philippe was the one who translated it into a reality.

Bellaïche: I met Lea some 20 years ago. I was working as camera assistant on a French documentary and the director invited me to a dinner at Michel and Lea’s house. “Lea is a lawyer, she has an office in East Jerusalem, she defends Palestinians,” the director explained. “Lea Tsemel?” I asked. I knew her name — she was famous. I even had her phone number in my pocket every time I went into the field. Lea’s number was a staple among journalists and documentarians. She’s the lawyer you could call if the authorities restricted or detained you for no good reason while doing your job — and who would help you for free!

The dinner was nice and the hosts simple and generous. Lea was far from what I had imagined a human rights lawyer to be. Instead of a pompous, stern, righteous, embittered intellectual who carried justice on her shoulders like Atlas, I encountered a cheerful, practical, direct woman who was “very Israeli” and not at all hopeless. I was so surprised. When I asked about her work she didn’t answer with universal declarations on human rights, but told me something super simple: “Everyone deserves a good defense, and Palestinians can be defended in Israeli courts. And since they can be defended, they must be defended. And I am one of the people who does so.” That first impression was very strong. So strong in fact that even though I got to know her much better later on, there was something about that first impression that I wanted to share with the world.

Filmmaker: Lea’s aggressive fearlessness has served her well throughout her career, though I’m guessing that a barnstorming personality might actually make production itself difficult. Did you feel that Lea was trying to direct or shape the film in any way? And if so, how did you maintain control?

Jones: Lea is a pussycat! We know that might sound funny when you see her doing her thing all fast and furious throughout the film, but when people don’t pose a threat or mount an obstacle there’s no need to bulldoze them.

Bellaïche: Of the dozens of documentaries I’ve filmed rarely have I encountered a subject who submitted so fast to the vérité logic, to the initial artifice which, when it works, turns into an organic process. Lea’s lack of self-consciousness has nothing to do with being unaware of the camera — she is both media literate and media savvy. But her ego is, well, different. If the phrase “Lights, camera, action!” were used in documentary, the word “action” would be Lea’s trigger.

Jones: Tiny as she is, she needs no pedestal. And smart as she is she’s more of a doer than a thinker. She plays herself naturally rather than performs herself superficially. And Lea is a person who devotes herself fully. In our case she devoted herself to the making of the movie — and to us, its makers. Not once did she say no. (She’s too clever for that. After all, she’s a lawyer, a persuader.) She gave us her trust, and we reciprocated with our integrity. Lea likes a project, any project. If you think her workweek ends after 50 to 60 hours of running from office to court to jail to prison to the Ministry of Justice, think again. She has family, friends, a feminist support grou, and always keeps a random person-in-need on hand. As her daughter says in an interview outtake, “My mother thinks she’s the handyman of the universe.”

Filmmaker: Can you talk a bit about the editing process? You move back and forth quite a bit between your own filming of Lea’s present-day cases and a vast amount of archival footage related to her past landmark trials.

Bellaïche and Jones: The original treatment focused almost exclusively on past cases, of which there were many. We knew we wanted to find one current, emblematic case, but hadn’t bargained on finding one quite so compelling. When the saga of the boy came into Lea’s office things took a turn. We started documenting it in full. At some point it seemed like there might be no need for the past cases — we had a “character-driven drama” on our hands. But we also knew that Lea’s story couldn’t begin and end there, and that no single case could possibly represent all the important issues that her personal, political and professional life have entailed.

So first we edited the real-time footage, and then we scripted a handful of past cases into the story. We started conducting interviews, doing archival research, and conceptualizing the look and feel (for we knew that this material would constitute the “material culture” upon which the animated effect — that conceals the identities of her clients for both legal and ethical reasons — would be based).

Then, as can be expected, we edited the past cases and each was like a little movie unto itself. The film was way too long, and we were biting off way more than the average viewer could chew. So began the painful process of cutting, shaving, whittling, and cramming everything into place. It hits you every time — what a strange and cruel medium!

Filmmaker: Your film centers almost exclusively on Lea, her colleagues, and her immediate family. Why did you choose not to include the voices of the “opposition” — say, the judges she appears before (and often loses in front of), or perhaps public intellectuals who consider her misguided or even a traitor to her nation?

Bellaïche and Jones: In our dream movie they were there too — prosecutors, judges, secret service interrogators. The people who love to hate her and hate to love her. Each past case was supposed to include a protagonist and an antagonist in addition to Lea herself. In the last film we made, Gypsy Davy (a portrait of Jones’s flamenco guitarist father that played Sundance 2012), we interviewed friends, fellow musicians, and aficionados. None of them made it into the final film. In the end, we cut a movie with a nuclear family of 11. We believe that people should never be mere storytelling instruments or “syncs.” People should have a screen presence, however brief, that goes beyond words — a raison d’etre that is deeper than a sound bite. With Advocate there simply wasn’t enough room for everything or everybody. When it came to the backstory we privileged Lea’s nuclear family and two counterparts, one Palestinian and one Israeli.

The “vox popoli” comes through in archival news reports and headlines. The people who are absent from our story are, at the end of the day, the ones who manage the dominant Israeli narrative on “security.” Had we brought them in it would have been to complicate that narrative. As one military court judge reportedly said, “If Lea Tsemel didn’t exist, we’d have to invent her.” She’s the boy pointing at the emperor and calling him naked. In essence, she’s highlighting the legal system’s most fundamental flaw — that the occupier is judging the occupied. Yet she’s also the boy with his finger in the damn, trying to keep the flood of injustice from drowning us all. Early in the filming process we understood that Lea’s point of view is unique, and that sticking to her subjective perspective would be far more captivating and coherent cinematically.

Filmmaker: Considering the widening chasm between American Jews and Israeli Jews I’m guessing our liberal audiences here in the States might be more inclined to wholeheartedly embrace the film. What’s your rollout looking like? Do you plan on screening the doc in the occupied territories?

Bellaïche and Jones: Two decades ago the friendliest audience for a film critical of the dominant Israeli narrative was to be found in Israel itself. That’s no longer the case. If Israel has long had a human rights problem it now has a civil rights problem too, and the chilling effect on Israeli Jews is palpable. We say this with modesty, for we too have found ourselves shivering and stuttering at moments. Moving from the comfort zone of armchair activism to witch hunt mode is an adjustment. With that said, we have an Israeli channel and film fund on board, in addition to various international broadcasters and foundations. So while the current government is trying to censure criticism, especially in the arts, and there will likely be people (both in positions of power and in the public at large) who take issue with the film, we are not alone.

Lea pushes the praxis of a human rights defender to its limits, forcing us to ask difficult questions: Are human rights indeed universal? Can civil rights really be guaranteed? Must political solidarity be unconditional? And what happens to these categories when a victim is also a perpetrator? While such questions have always had global relevance, in the war-on-terror and migrant-crisis eras they take on even greater resonance. As more countries enact legal states of emergency (which Israel has enacted since the day it was established) that undermine the basic tenets of civil and human rights, Lea’s localized, decades-long struggle carries important lessons.

As Lea said 20 years ago in a TV interview, “I am the future.” Since 1967 an estimated 800,000 Palestinians have been arrested, detained, jailed and imprisoned with and without due process. Lea has literally represented tens of thousands of them. It is with these people — the ones Israel has criminalized and incarcerated en masse — with whom Israelis will have to share their futures. Lea Tsemel understands this better than anyone. She spoke truth to power before the term became popular and she’ll continue to do so after fear makes it unfashionable. As such, Lea’s a model we’re hard-pressed to preserve, in Israel/Palestine and elsewhere.