Back to selection

Back to selection

Focal Point

In-depth interviews with directors and cinematographers by Jim Hemphill

“Is Evil Outside of Us, Or Does It Come from Within?”: D.P. Fred Murphy on Shooting Evil, Wide-Angle Lenses and Working with Wim Wenders

Evil

Evil Evil was one of the best new television series of the 2019-2020 season, a thoughtful consideration of a vast array of moral, spiritual and sociopolitical issues in the guise of a supernatural procedural. The show follows Kristen Bouchard (Katja Herbers), a clinical psychologist with a complicated family life who teams up with David Acosta (Mike Colter), a haunted ex-journalist who works for the Catholic Church as an assessor; he investigates – then confirms or debunks – incidents involving miracles, demonic possessions, and the like. Series creators Robert and Michelle King (the husband and wife team responsible for The Good Wife and The Good Fight) use the dichotomy between the pragmatic Kristen and the spiritual David as the starting point for a sophisticated and provocative inquiry into the nature of belief and the origins of evil – all the while delivering the goods in a show that’s genuinely scary and often diabolically funny. It’s also, at times, heartbreakingly tragic and poignant, and it consistently incorporates real world horrors in ways both timely and timeless.

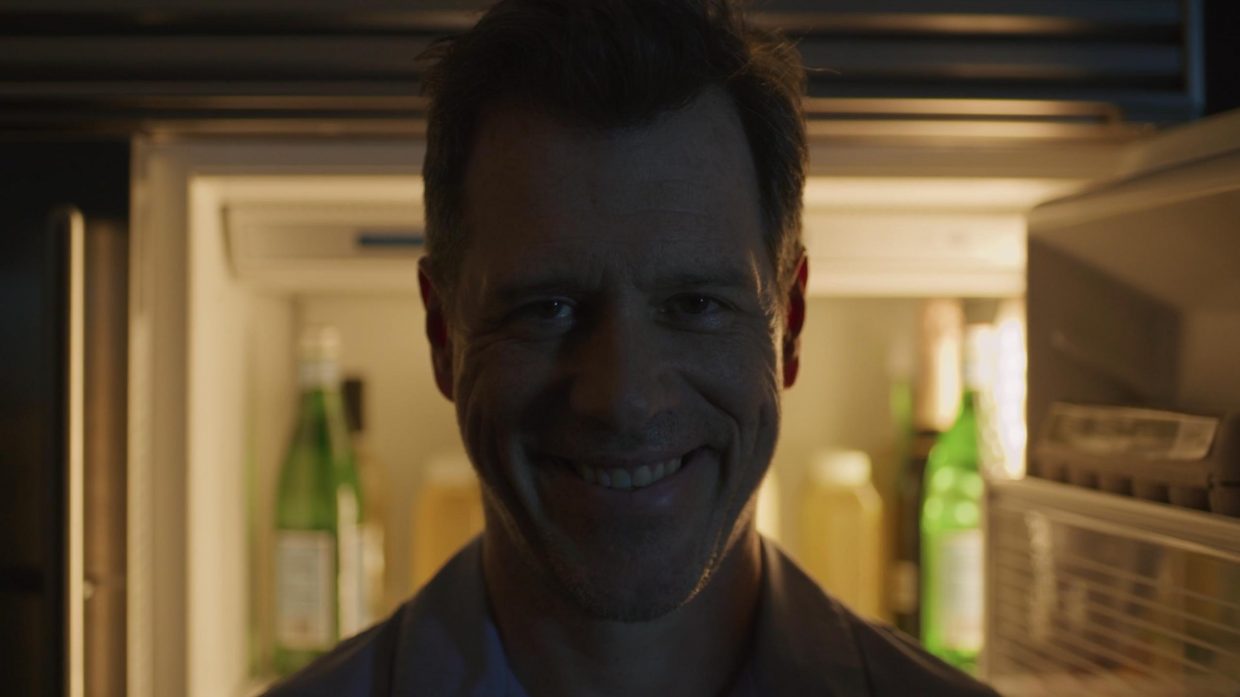

One key to Evil’s impact is the eerie, gorgeous, and singular visual style established by director of photography Fred Murphy. A frequent creative partner of the Kings on shows like The Good Wife, The Good Fight, and Brain Dead, Murphy shot six of Evil’s 13 season one episodes, including the pilot directed by Robert King. (Other episodes are photographed by Tim Guinness and Petr Hlinomaz.) Finding the ideal visual corollary for the series’ philosophical complexity, Murphy employs a precise and highly effective approach to composition and lenses that strikes the perfect balance between the recognizable and the uncanny – the world of the show looks and feels like our world, but something is always just a little off, and there’s a constant sense of dread and unease lurking beneath the familiar surfaces. There’s a deliberate and meticulous quality to Murphy’s images that makes Evil both beautiful (practically any shot from the series could be hung on the wall as a still image) and absorbing – using almost subliminal shifts in perspective, the series has a hypnotic effect on the viewer that makes it as visceral as it is brainy. It’s the latest in a long tradition of great work from Murphy, who began his career with several landmarks of the American independent film movement in the 1970s (Not a Pretty Picture, Girlfriends) before going on to collaborate with Wim Wenders, Paul Mazursky and John Huston. With the first season of Evil arriving on DVD this week in a great package that contains behind the scenes material and deleted scenes (the show is also streaming on CBS All Access), I got on the phone with Murphy to discuss his approach to this unique series.

Filmmaker: Let’s start with the origins of your involvement in Evil. Obviously by this point you’re a trusted collaborator of Robert and Michelle King, so where was the series at when they brought you on? Was it just an idea, or did they have a script?

Fred Murphy: They already had the script, and it was really good. I liked how dark and interesting and complex the characters were, and how philosophical it was – that it was about faith and belief versus non-belief. What does that mean in a practical sense, and what is real and what’s in our imagination? Is evil outside of us or does it come from within? My involvement began with the effort to find a location for the main character Kristen’s house, which started when they showed me an extraordinary picture of a railroad bridge running over a house in Queens. That started the idea that Kristen should live underneath a gigantic railway that would be roaring over her head all the time, giving the sense of chaos and an evil presence lurking above her.

Filmmaker: Yeah, one of the things I’ve noticed about the show is that the compositions are very vertical. You’re always drawing the eye to the top of the frame or to areas above the characters, which is unusual, especially for network television.

Murphy: That comes from that spiritual theme I mentioned, the idea that we’re always looking up – there’s always something above us. We were influenced by a couple of films, most notably Night of the Hunter. There’s a scene in that movie where Robert Mitchum kills Shelley Winters, and most of it is played in a wide shot in the upper story of a house with an extremely pointy roof. The impression is that it’s pointing up to heaven and he’s standing there with a knife in his hand as a shaft of light comes down on him, and it’s quite dramatic. There’s a large sense of seeing the architecture above in that shot that inspired us, and then another film we looked at was the Polish movie Ida, which is interested in the spiritual and is framed with a huge amount of head room – I believe the director said he wanted to leave space for the angels. Anyway, you’re right that there’s a great effort to design the sets in a way that emphasizes the spiritual presence above the characters. When you see David praying in his room in the second episode, that’s obviously influenced by Night of the Hunter.

Filmmaker: I love that you mentioned Night of the Hunter, because I think Evil has a similar blend of disparate tones, walking a line between realism and supernatural elements that’s quite unusual…the naturalistic scenes all have something just a little off, and the supernatural scenes are more rooted in the everyday than you might expect. What are you doing in terms of lenses and lighting to create that feeling?

Murphy: We shoot most of the show on wide-angle lenses, and when it’s not a wide-angle lens it’s a relatively long lens. We’re either shooting around a 15mm to a 29mm or 100mm to 135mm, not much in between. That’s just my personal prejudice and where my intuition leads me, and Robert, who directed the pilot, leans the same way. We both like wide-angle lenses so that you can see space around people even when the camera is close and feel the environment they’re in. Or we’re interested in the distortion. Then often, in the middle of that, we’ll go in the opposite direction and really isolate them. In the pilot there are several interrogation scenes where the wide shots are probably with a 21mm, or an 18mm, or even a 15mm, and the closeups are probably all with a 135mm. It’s an extreme juxtaposition with extremely tight close-ups in which the face is filling the frame.

Lighting-wise, the basic mantra was that our heroes live in warm, cluttered, modest places while the villains occupy antiseptic, modern, expensive, large habitations, whether it be an office or a house or something else. So in Kristen’s world, we have a warm tone, but often the shadows are cold, and if the light falls off somewhere into the darkness, usually that darkness is blue. There’s always a simple juxtaposition of warm and cold in the private spaces, then in public areas like the courtrooms the color is more neutral. On occasion when there’s a scary event we’ll go in the opposite direction of convention and put it under a very bright light, but mostly it’s that mix of warm and cold.

Filmmaker: And how planned out are your shots? The compositions are very precise…do you storyboard?

Murphy: No, there’s not much storyboarding aside from big effects scenes, but we do pre-plan everything. There are alternating DPs on the show, so we do have time to prep, and in prep with the directors we go to the locations and the sets with viewfinders and plan out all the shots. Otherwise, on these television schedules, you’re not going to make it. You can change your mind of course, and we do, but you can’t fool around trying to figure things out on set.

Filmmaker: How do you maintain consistency when you’re working with different guest directors every week?

Murphy: Well, my A operator Aiken Weiss and I just inflict our prejudices on them. Aiken and Robert and I all have a predilection for the same kind of shots. But we’ve actually got a lot of terrific directors on the show, and for me what they mostly bring are staging and blocking ideas. That’s what I’m always looking for in a director, great ways of organizing scenes and blocking the actors. I’m not doing that – I’m desperately trying to light the scene and get the cameras in the right place.

Filmmaker: How many cameras do you typically shoot with, and what types of lenses are you using?

Murphy: For the most part it’s two cameras. Often it’ll be two wide shots together, or two tight shots together. One camera’s on the floor, one camera’s on the ceiling, that kind of thing. The show is shot on the Panavision DXL2, which has terrific range from light to dark and has a very different sense of color from other cameras – it seems smoother, less contrast-y. As far as lenses, I use Leica Summicron primes. We have a zoom lens, but it’s only used if we need a very long lens or need to zoom for some reason. The reason I use the primes has to do with a sort of discipline; you lose a little time because changing lenses always takes longer than you wish, but it forces you to understand why you’re using a 15mm, as opposed to all of a sudden zooming out to 15mm, zooming back to 20mm, and fishing around. It forces you to use the lens correctly and think about why you’re using a 15mm as opposed to the 25mm. And it eventually becomes second nature, knowing which lenses to use where.

Filmmaker: Some of the scariest stuff in the show is the material with George, the demon-like creature who visits Kristen at night. How does lens choice factor into shooting those scenes and making them as creepy as possible?

Murphy: Filming the pilot, a huge effort was involved making George look interesting and real and scary. Robert had this idea that we should film George with a long lens, and everything else with a wider lens. We did a series of tests to come up with a color and lighting style that would work, and basically I used Arriflex SkyPanels to light him – I used those on a lot of the show, actually. They’re marvelous because you can go through the whole gel book and program what you want into the light, and it will come up with that color. So I tuned all the George scenes to a particular color, which is Lee 196. All the night scenes in Kristen’s bedroom that look bluish are lit with that color, whereas the rest of the night scenes are lit with a more normal, shall we say, night blue, which is usually daylight blue, with the camera set at 3200 or tungsten balance.

Anyway, if you look at the pilot, you’ll see that in the beginning Kristen is looking at the door, and she’s looking at the wall, and then there’s a sort of wider shot. And the wider shot was done with a 75-millimeter lens. We took the back wall out and the bed was way out of the set. Her feet were in the foreground, and the covers are in the foreground. And it was a good 20 feet outside the set. Then George appears, and there was no trickery – he was just hiding in the darkness. He turns toward Kristen and starts walking toward her, and it’s a huge distance he needs to walk to come into a close-up – we don’t show him walking the whole way. There’s a cut back to her, then back to him and he has come into a close-up at the foot of the bed. After that everything is wide-angle lenses, so the next time you see George it’s with an 18mm or a 21mm with him looming on top of her. Your first perception of George is weirdly far away and dreamlike, and then there’s a startling jump in perspective when he’s on top of her in bed and we’re back to our usual wide-angle look.

As far as lighting him, it’s as dark as I could possibly make it and still have it work on broadcast television. Basically, it’s one-source lighting coming thru the windows, along with some warm lights sneaking through cracks in the doorway, lighting the ceiling above his head, things like that, and then the old trick of a pen light in his eye. The gaffer had a little flashlight and he would be holding it, and George had contacts. They would reflect the light, and that created that nasty yellowish glow in his eyes.

Filmmaker: You mentioned making it work for broadcast TV, and the thing that I’ve loved about all of your television stuff that I’ve seen is that the lighting is very subtle and nuanced. Is that an ongoing challenge, getting the texture you want and going as dark as you want to go and everything like that?

Murphy: Of course. Absolutely. I’m not a particularly technical person. I mostly do everything by eye, looking at the monitor and looking at the set. I’ll look at the scope, but not much – I only pay marginal attention to the scope. And obviously I don’t use a light meter anymore. They don’t seem to work in these circumstances very well. I should say everything is shot at two, for the most part – everything is wide open. We’re working at extremely low light levels. This camera’s 1600 ASA, so you’re working at four foot-candles, which is not enough to read a book by. It’s an interesting challenge. But to go back to the idea of delivering for broadcast, it’s somewhat guesswork, and then I’ll go to the post house and sit down with my colorist, who’s got a better handle than I do on what the network will approve, and we’ll take it to the edge of what we think broadcast will accept. The lighting is done already and it’s 99% there, but we’ll take it to the final edge as far as darkness goes.

Filmmaker: Before I let you go I have to ask a non-Evil question, because earlier in your career you shot several of my all-time favorite movies – John Huston’s The Dead — and a bunch of great stuff with Paul Mazursky. You worked on Wim Wenders’ The State of Things…what kinds of things did you learn from those experiences that inform the work you do now?

Murphy: With Huston I was working with a legend, so every day I was terrified. But John left a lot of it in my hands and in the assistant director’s hands. At the end of the day he would tell us what we wanted. “Fred, I’d like the camera to start here, and stay with so-and-so. And then as he turns away, I want you to move across the room and find her over there.” He wouldn’t tell me what lens or anything. So, the assistant director and I would set it up, we’d even rehearse it with the actors, and then we’d show it to John. He’d say, “Oh, I love it. It’s great. Let’s do it.” Or, “No, Fred, let’s try something different.” He was fantastic – it would seem like the AD and I were doing everything, but it wasn’t really true. Somehow John was controlling it all in an almost mysterious manner.

Mazursky was another great, the most wonderful, funniest and most brilliant man. The main thing he gave me was the idea that you should always leave yourself open to something that’s happening, even if it goes totally against your plan. If you realize the new thing is better, do not hesitate. Jump right in. Don’t go back to your old plan if you see something better. And he always did that. He was just so much fun to work with. He made it very enjoyable, every day. We were doing Enemies, A Love Story, and he came up and whispered in my ear. He said, “This film is going to be terrible. We’re having much too much fun.”

Wim was really interesting. He had this amazing gift for knowing the perfect place to put the camera. We’d go to a location and he would spend a lot of time walking around and looking at things, and then he would somehow find the exact right place to put the camera for whatever particular thing we were going to do. He seemed to know exactly what emotion could be elicited by showing you something at a particular angle. I was operating on State of Things for Henri Alekan, and then he had to leave and I shot about a third of it. Henri was one of the great DPs – he shot Beauty and the Beast for Cocteau, along with many other great films. And he had the same ability as Wim, to find the emotion in the scene and pitch the lighting to express it, which is very hard. He would turn to me and say, “Oh, this is a very sad scene. We need a sad shot.” But what is the sad shot? It’s really hard to say because it’s so simple.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD and streaming on Amazon Prime. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.