Back to selection

Back to selection

The Past in the Present: Garrett Bradley on Time, Her Documentary about Activism and the Carceral State

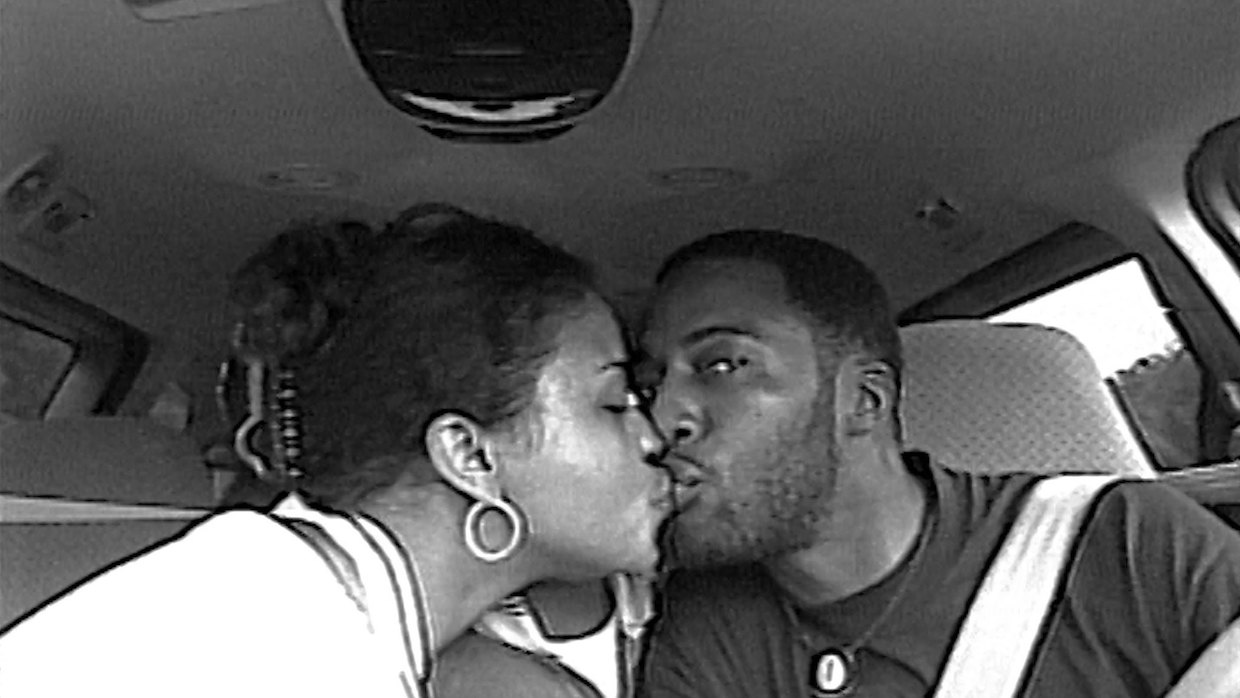

Fox and Rob Rich in Time (Courtesy of Sundance Institute)

Fox and Rob Rich in Time (Courtesy of Sundance Institute) Filmmaker‘s Summer 2020 cover story, Ashley Clark’s interview with Time director Garrett Bradley is being published online today for the first time to mark the film’s New York premiere this coming Sunday (with virtual screenings continuing until September 25th) at the New York Film Festival.

For over half a decade, New York-born artist and filmmaker Garrett Bradley has been steadily building an impressively diverse yet tonally and stylistically harmonious CV. Bradley’s work has encompassed film, television and the gallery space; short, longform and multi-channel ventures; and ambitious explorations of the porous boundaries between fiction and nonfiction. It has often focused on the landscapes and inhabitants of New Orleans, where Bradley has been based for much of her professional life, and the way that people’s day-to-day interpersonal relationships are affected by social and political systems. Both Bradley’s feature debut, Below Dreams (2014), and its follow-up, Cover Me (2015), are set in the Crescent City and offer keen, meditative portraits of millennials struggling to find themselves and one another. Bradley has made thoughtful short films on subjects as wide-ranging as online click farms in Bangladesh (Like, 2016) and earthquakes in Japan (The Earth is Humming, 2018), and she has directed fiction and nonfiction television (Queen Sugar, 2017; Trial By Media, 2020). Bradley was also a featured artist at the prestigious 2019 Whitney Biennial, where her single-channel video AKA—a dreamlike study of mothers and daughters within interracial families—was one of the show’s clear highlights.

My first substantial interaction with Bradley’s work came at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival, where I saw her extraordinary 30-minute film America, a silent omnibus rooted in New Orleans that aims, via a series of striking monochrome vignettes, to reveal and reinterpret a lost history of African American cinema. The film was inspired by MoMA’s discovery and presentation of the long-lost Lime Kiln Club Field Day (a Black-cast romantic comedy from 1913 starring legendary Black vaudevillian Bert Williams), as well as the findings from a 2013 Library of Congress survey that stated 70 percent of the American silent feature films made between 1912 and 1929 had gone missing. How many of these lost films were made by or featured Black talent at a time when the racist tropes of films like The Birth of a Nation (1915) were being enshrined as standards in U.S. cinema? Deeply moved by America’s poetic attempt to counteract this vanished past through the creation of original works, I built a program around the film at Brooklyn Academy of Music—Garrett Bradley’s America: A Journey Through Race and Time—in October 2019.

America had me extremely excited for Bradley’s latest documentary, Time, which premiered at this year’s Sundance. Shot in elegant black and white like the vast majority of Bradley’s work, Time is a companion to, and development of, her short New York Times Op-Doc Alone (2017), an intimate portrait of a family dealing with the realities of the prison system. Time focuses on the extraordinarily charismatic orator and prison abolition activist Sibil Fox Richardson (a.k.a. Fox Rich), who is fighting for the release of her husband, Robert, sentenced to 60 years in prison. Time is, by any measure, a truly remarkable work of art: a deeply sensitive treatment of exceptionally painful subject matter that bears not a trace of sentimentality. Time’s graceful compositions, flowing sonic landscape and at times breathtaking interpolation of Fox Rich’s home video archive footage cohere to form a singularly powerful experience. Time received rapturous reviews across the board and sparked a bidding war among major studios, which was eventually won by Amazon, who acquired it for $5 million.

In the middle of June 2020—an eerie and disturbing yet guardedly galvanizing moment of protest and pandemic—I spoke with Garrett Bradley by phone to go in depth on the roots and multiple realities of Time.

Filmmaker: How did you and Fox Rich meet in the first place?

Bradley: We met in 2016. I was in the process of making a short documentary with New York Times Op Docs, which became Alone. I had initially thought about that film being a series of intergenerational conversations between Aloné and other women who had found themselves in similar situations and had few people to consult because of the stigmas associated with incarceration.

I had worked with Aloné’s partner Desmond on my first film, Below Dreams. I cast that film entirely through Craigslist, and I got to know Desmond and Aloné very well. So, when he was arrested for a nonviolent offense (and ended up being one of thousands of men awaiting trial in a private prison for more than a year), Lon meanwhile had become a single mother overnight and was tasked with the very real responsibility of making major life choices, by herself, without the support of family or friends. Today, there are roughly 2.3 million people incarcerated in America (37 percent of whom are African American men). By default, this means there is double if not triple that number also currently serving time on the outside. So, the irony is that Lon in her isolation was by no means alone. Because of slavery and America’s systematic separation of Black families, millions of women are managing their heartache, their pain and loneliness on their own.

A way to address all of this was to facilitate conversations. Gina Womack, the cofounder and now executive director of Friends and Families of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children (FFLIC), helped hugely in my pursuit to build somewhat of a network for these talks. The first person that she said I needed to talk to was Fox Rich. Fox is actually in Alone, briefly, at the end of the film and makes a vivid connection between slavery and today’s prison system. So, I got to know her in the process of making that film, and she, I think, got to know me and my own process as a filmmaker. I think that experience put in place a level of trust and shared language for us in working through her own story for Time. I had felt, having made Alone, that there was a real urgency to address our unjust prison system from a Black feminist point of view because it is from that perspective that it is most abundantly experienced. Aloné was my age and had never been in this situation before—she was at the very beginning of understanding the system. Whereas Fox had, at that point, been through it for 19 years. It was really important for me to not let the conversation around incarceration from this point of view end with Alone. There are many, many, many stories that could (and hopefully will) be told, beyond Time, from this perspective.

Filmmaker: At what point did it become clear to you that Fox had an extraordinary archive of home movie footage that would go on to become such an essential part of the film?

Bradley: I think we had shot off and on for about a year. It was a relatively short production altogether, maybe no more than two and a half years from start to finish. I had always considered it to be a sister film to Alone, thematically but also with the intention of it being another short Op Doc. And I do still see it as a sister film, regardless of running time. On the last day of shooting, I remember saying to Fox, “OK, I’ll be back in a few months to show you what I have. Thank you for your time and for trusting me.” She said, “Hold on a second. I have something for you.” It was this black bag filled with Hi8 tape. She just said, “This may be useful to you in some capacity.” And I remember driving in my car with it and being so nervous to have something of irreplaceable value in my possession. Fox had given me her family archive, her life archive, and trusted me to not only see the right things, but even just to not fucking lose it, you know? To not fuck it up. Once we started watching it, it became really clear that this was not going to be a short film. And there were so many exciting challenges as a result of that because I’d been shooting it in such a specific way the whole time, with a specific idea of what the outcome was going to be.

I’m not interested in entering somebody’s life and following every moment of their day, then taking that into the editing room and finding a story. I try actually to spend enough time with the person that I can anticipate what their days look like. I can even anticipate, to a certain extent, their lifestyle and physical movement in the room so that my camera just has to be in one place, and everything can unfold in front of it. There’s a certain static stillness and understanding in what’s to be anticipated in our current-day footage. All of that was completely thwarted going through the archives. It was texturally different, tonally different. So, trying to find a way to bring them together became the beginning of Fox and [me] really, truly collaborating with each other across space and time.

It also, for me, became a challenge of what it means to understand authorship and what mixed media is in the context of documentary filmmaking. It really feels spiritual, to be honest with you, because there were also these moments that were actually exactly the same—where the camera would be in a particular position with her sitting at her desk. She spent a lot of time in her office working on the phone; 19 years before that, if not even longer, Fox was putting the camera in exactly the same place in her office in Shreveport. So, there was this incredible synchronicity that existed with the footage. Remington, her eldest son, was often tasked with holding the camera and shooting her hosted events. She was a director, and she had a vision that he would both execute but also use for his own curiosity. Great moments of him zooming in on people’s hands writing and women in the audience listening intently; sometimes, the houses passing by on the side of a highway. In those moments where you could make the formal connections, I tried as much as possible with [Gabriel] Rhodes, who cut the film, to really lean into that. In terms of emotionality, the archive offered a level of vulnerability that was less visible 19 years later, when we met. Fox remains the loving, free spirit that we see, but I think the system also demands a version of exceptionalism that she seemed a bit free from as a younger woman. The system to a degree had shifted her into the woman that I met, not the woman that she was.

Filmmaker: That follows on to the idea of performance with Fox. She’s a real performer, a larger than life character, and we see her delivering multiple powerful speeches to rapt audiences, whether at church or in support groups. I’m so interested to hear you talk about how you navigated those qualities in making the film.

Bradley: We’re in the moment of revolution in our country. The strength of Black women and the acknowledgment of how Black women hold this country together is just now starting to be a part of the conversation, thankfully. But even six months ago, a year ago, when we were cutting it, the question of audience response relative to Fox’s strengths came up quite a bit. Is she too strong to be likeable? Does her passion get in the way of our loving her? How do we keep the door open? I think the world is ready for those concerns to be moot points, and the film is speaking to those who already know that. But coming back to those concerns as they relate to “performance,” the archive unveils in my mind a powerful account of how her matriarchal, political and personal strength evolved over the course of 21 years. We see revolutions within her, which are then reflected out in her pursuit to reunite her family. Without the archive, we would have leaned too heavily in the current moment and would have missed an opportunity to show why, and to what extent, that strength is required. That desire of an audience to witness or understand that arc is a human need—it’s what I think makes us human.

Filmmaker: Can you speak more about the nature of your and Fox’s collaboration, especially with her voiceover?

Bradley: I did a lot of audio recordings with Fox, just as I did with Aloné for Alone. I think every project that I’ve done has started off with a series of recorded interviews and conversations. From that, I usually will pull pieces of information that seem crucial, write them and share them with the person. It helps both of us to get a sense of linearity because I think even if a film is about you, it can be hard to see your own story in linear terms. When it came down to distilling information into clear, distinct sound bites, we would write and rewrite together. It would be a matter of me saying, “OK, we need to address the robbery. Here’s some suggestions for how to do that in a concise way, at the pacing of the film.” She has an incredible voice and talent for speaking. It would have been naive of me to expect her story to fit into my words or process alone. I really see myself in some ways as a facilitator or somebody who creates prompts that then can be owned by the people whose story it’s about.

Filmmaker: I wanted to ask specifically about the opening montage. I was struck by how much, and how economically, you are able to convey about the story and character of Fox and her family with the edit of the archival footage.

Bradley: I have so much respect for how Fox took the reins of her life and the world around her. People are magnetized by her, and yet she is the one who will pull the focus away from herself to her larger family. I’ll never forget when she saw the film before we officially locked picture, and she said, “I didn’t expect to have so much of me in it!” I think anybody who watches the film would be like, “How could it not be so much about you, you are the sun!” So, when we talk about the beginning of the film, how to introduce the story and to create clear parameters for how we are quantifying value throughout, it was important to, I think, incorporate her value system equal to my own. It was a huge part of the conversation of how to open the film. Do we open it with Fox just introducing herself and talking about her own journey? Or do we try to find a way to understand this woman on her own terms, which is that she is a part of a collective and can’t be separated from it?

Filmmaker: Could you tell me what you shot on, and talk about the choice to shoot in black and white? It’s a striking textural choice.

Bradley: We shot on a little Sony FS7 and Canon 70–200mm zoom. As for the black and white, there’re three ways to answer that question. The first is that, with the exception of one recent film, AKA, I’ve been working in black and white for several years. I think, truly, my eye was only seeing in black and white. I’d always seen this film in black and white, and that was also partially true of Alone, which was black and white because I was making America at the same time. I didn’t consider it on a nonformal level until Lon’s oldest son saw the film before picture lock and made the observation that, “It’s like we’re always in present time. There is no past, there is no future.” I wish I could take credit for being that smart. I really just liked the way it looked.

Once we started getting into the archive—I think that’s the second part of answering this question—there were real formal and aesthetic challenges that were easily resolved by using black and white. It was really important to me that the film felt like a river, that it felt fluid and consistent, because we’re going back and forth between times, shifting through space. The textures and the materiality of the archive up against the slick clean zooms of the present day footage felt to me like they really worked against one another. I also thought that the music—which was Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou’s piano album that she recorded in 1964 to raise money for an orphanage in Ethiopia—was going to hold the film so much better if the visual element felt tight. Also, I think it is important to remember that black and white film used to be our only option. Then, color film became not an alternative but a standard. I guess, in my opinion, film is still too young for standards.

Filmmaker: Can you talk about the editing process?

Bradley: Gabe and I were editing remotely the entire time. I was living in Italy, and he was in New York. We started really talking about what was important to me. I wanted to know what he saw, and he wanted to know what I saw. It was, I think, crucial that we first created some groundwork for the way in which we saw things, to put it simply. He’s a White man, I’m a Black woman, we’re dealing with a Black woman’s story and a Black family story about love and incarceration. It was crucial that when he looked at a piece of archive, or when someone said something, that we were both in constant communication about what was being translated, how things were being translated. That never stopped; we had to check in with each other every step of the way. There is a whole other conversation about the real anemia that exists in the industry, the lack of editors of color and that was something we needed to address from the beginning and not shy away from.

I learned a lot from Gabe in working with him, particularly on structure. I think that is important to mention because I’m somebody who can live in images and sound for days and days and days. One example would be in my initial refusal, for instance, to address why Fox’s husband had been arrested. A lot of people wanted to know that, and I didn’t feel that it was important information. “Facts,” I think, are really interesting things, particularly when it comes to when we’re talking about justice because there are emotional truths that can’t be proven in an unjust system. So, how do you deal with that in a filmic space? Gabe basically worked really hard on building out the backbone of the film, what he and I both agreed to be facts, you know? From there, we built the poetry, and every step of the way that poetry was always tied to something that was structural to a certain extent. But the structure never overrode these less implicit forms of truth and storytelling, if that makes sense.

Filmmaker: I noticed some aesthetic resonances with Time, in particular some low Dutch angle shots of Fox orating, which rhyme with some of the most memorable shots in America, like the baptism scene. It’s beautiful to watch you developing a style that’s so you. Were you thinking about this consciously while making Time?

Bradley: I don’t separate style or form from story or subject matter. Both, I think, need to be inseparable—unless of course you are intentionally interested in separating them, which is cool, too. So, when you are working with an archive, [material] you have not conceived, it becomes for me about mining the moments where the two elements do come together. With America, for instance, Bert Williams is wearing black face. But he also happened to be the director and one of the producers on the film. The role he played in that production was a reflection of his own personal power and the social progress of the picture. What moments could I pull from that film [Lime Kiln Club Field Day] that unequivocally illustrated that? The angle of the camera, the choreography of performance and the interactions between he and his collaborators need to all be in sync to tell that story—in a single frame. So, in the 1913 footage we see him in this playfulness, in this placement within a larger body of actors who are not in black face, and we see him giving direction to a White producer (in 1913). These moments tell us something using every element that film at that time could be composed of. Time was an interesting twist to this approach in that it being a family archive meant it was in sync with itself already. The style and the subject matter could not be separated. The challenge was how to create a meaningful and equal dialogue with the footage I had shot.

I think, honestly, part of being a director (especially working in documentary) is transparency around your agenda. The fact is that I have one. My agenda in America was to show that there was joy and there was power and there was control and there was real direction, even in 1913, with Bert Williams. There was creative innovation. With Fox, the agenda was to show how a woman holds a family together over the course of two decades and doesn’t lose herself in the midst of it. That there is a valid purpose to her strength. The choice of how to work with the archive was based on those beliefs. Another interesting issue raised in working specifically with a news archive is that you are then sifting through an often one-sided viewpoint that you don’t always agree with, and you have the challenge of trying to flip that on its head in a contemporary context and with the benefit of a future perspective. With the Amadou Diallo episode [of Netflix’s Trial By Media, which Bradley directed], it was critical that when we hear Jeffrey Toobin talk about crime in New York that we focus our gaze on the police—not potentially innocent people standing on street corners. Images stay with us and, as I mentioned earlier, the facts can become abstract. If we don’t turn our

perspective to be more precise, we end up perpetuating an implication, and what is implied buries itself in your mind, over time, as the truth. So, the way the camera is used, and the way the archive is reused, is a power that should not be underestimated. Straight up.

Filmmaker: I love that. I love that you’re drawing a connection between the intentionality of the depiction of authorship between Bert Williams over a hundred years ago and Fox today. I think it’s really beautiful. Moving on from that, I wanted to ask about one especially striking scene in Time. It’s the second time we see Fox on the phone awaiting an appeal ruling, and there’s this clanking construction noise outside. The way that you structure the scene is extraordinary because you zoom in slowly on the machinery that is making that noise to begin with, before moving inside to be with Fox. It provides a soundtrack to the scene, and it sounds like a heartbeat, but it also gives the scene even more tension. It struck me as an incredible marriage of form, theme, emotion, where every single choice seems to count in some way.

Bradley: I think there’s a tendency when making films about living people to kind of recap their lives. Just by way of the fact that we are making a film, we have a camera and we’re shooting somebody’s life, it somehow seems intuitive to then take that footage and have it feel as if it’s an overview of important things that have happened. I’m actually more interested in trying to create an environment for people that feels as though you are living with a person, that you are living life as it feels, alongside them. Memory and our thoughts are what take over most of our minds throughout the day. Any traffic that’s outside, any construction, they’re happening simultaneously with us being on the phone, grocery shopping, to any series of obligations that we have. How can I make films that honor the reality of that experience? I think that’s always been an intention. It’s why I shoot the way that I shoot, as well. I don’t want to be behind somebody every moment, I want to be with them.

That day, there was construction outside, and it was shitty. We actually shot that early in the morning before going up to film inside, and we were lucky to be able to pick up a bit of the audio that was clean, and we put that underneath. So, it was a creative choice based on what was actually happening and what she actually was experiencing. There are these questions I think particularly young people should keep in mind when they’re making films: What is the purpose of clean audio? Why do we need that? What is that supposed to make us feel, to not hear any other things? We get to choose what people want to hear, and we can also include reality in that and it doesn’t actually distract us. It doesn’t distract us in real life. It might actually add to our understanding of it. That’s where I think things get really interesting, when we try to work through simultaneity in the confines of a two-dimensional medium. I feel in every one of Robert Altman’s films you see an excellent obsession [with] that possibility.

Filmmaker: Speaking of surroundings, I feel that the key shot of the Time is the drone shot of the Louisiana State Penitentiary (nicknamed “Angola” after the former plantation that occupied the territory) with the church smack dab in the middle of it, then behind it these acres of space with such a charged, upsetting history, all in one place. It brings everything together in a psychogeographic way. I’d love you to talk about that image.

Bradley: Angola prison is 18,000 acres. It occupies 28 square miles. That shot was really important. And to be honest with you, every time I look at it, I’m actually disappointed by how little it shows in terms of the magnitude of that prison. We literally had to drive to Mississippi and fly a drone over the water to try to get that shot. And even then, we only got one fraction of it. I think it’s 12 plantations that have been amassed into one prison facility. So, seeing that was crucial. I think that part of the power of incarceration is its apparent invisibleness and not having any kind of evidence for what it looks like and what its magnitude is. When we think back on the Vietnam War, part of what inspired so much action was the ability to see the actual coverage of what was happening. We have since then lived in an era of the green screen, where we are completely detached from the atrocities that exist behind it. So, despite not being able to get as much, frankly, as I wanted of the prison, it felt to me crucial to at least have some evidence of the landscape, of the magnitude of it.

Filmmaker: I have to ask you about the scene that everybody was talking about at Sundance in terms of awestruck wonderment: the love scene between Fox and Robert in the car, following his release. How did it happen? How on earth did you build up enough trust to make that viable? It feels miraculous in a way, like, “I can’t believe I’m even watching this.” Can we talk about that?

Bradley: This is again related to knowing the people that you’re making films with, and not treating them as subjects. I asked Fox over the course of filming, “What’s the first thing you’re going to do when he gets out?” And when I say, “When he gets out,” that’s because I also understood that Fox exists on a plane of manifestation so strongly, to the point where sometimes I would even be confused: “Wait, is this happening tomorrow? Oh, wait, we’re manifesting. OK, cool.” That was a learning process. I knew what was going to happen when he got out, so it was just a matter of talking with her about that in advance and saying, “What are your thoughts on having a camera in the car?” She agreed to do it. I remember, I was driving in my Honda behind them, and Nisa East [a cinematographer on Time] was with them, in the passenger seat up front. They were in the back of the car, and I said to her, “Make eye contact with Fox. She will let you know if it’s cool or not, and just shoot that shit in slow motion, cause there’s no other fucking way you’re going to get it on the road.” And, you know, I think any filmmaker knows that this is a job about communication, you know? First and foremost.

Filmmaker: Your film made me feel very hopeful about the state of nonfiction filmmaking. It’s a broad question, but how do you feel about the current landscape?

Bradley: Every revolution introduces a new set of symbols, new iconography, a modification of genre. This happens both within the movement and its aftermath. WWI inspired [Kurt] Schwitters and [Robert] Rauschenberg and [Marcel] Duchamp to take trash off of the ground and turn it into art. WWII introduced neorealism. We saw it also in the 1960s with Charles Burnett, Billy Woodberry, Julie Dash and the L.A. Rebellion filmmakers, and I think we’re there again now, you know? The protests in Watts proved a major turning point for Noah Purifoy, who I’ve been thinking a lot about, being out here in the desert, and who went from designing high-end modern furniture to taking rubble from those protests and introducing a new value system around capitalism and form. We’re there again—new perspectives and their ability to be seen and heard will introduce new symbols, new forms.

Filmmaker: Amazon purchased Time for $5 million. Whatever way you look at it, that’s a huge deal, right?

Bradley: Cinetic did the deal for us, and I had no reference point for what selling films at Sundance looked like. The Wolf of Wall Street, maybe? I remember being asked at the beginning of the process, “Garrett, what is most important to you with this sale?” I think a lot of filmmakers are asked that question at every stage of the process: What is it that you want? Artists are never really asked that question, which is interesting because it implies more freedom to not know. But what ended up being important for me was understanding the market I was working in. When we talk about acquisitions, we’re also talking about value that is both concrete and symbolic. It was important for me that the film sold at a level that indicated to the industry that films by, about and for Black people are equally as valuable. So, I was less interested in how somebody made me feel on a personal level than I was about the potential of a message. The bigger picture is always more valuable than the moment. And the moment, if you’re paying attention, is what gives you the ability to affect and inform the bigger picture. So, every big decision I make is coming from that point of view. We are a part of a larger system, and if you aren’t in tune with what it’s doing and how it works, I can’t imagine you’d be able to push it in any meaningful way.

Filmmaker: And this industry has not traditionally been a very welcoming, forthcoming place for Black women. So, there is absolutely something very powerful about you navigating that and having real agency in that process. Do you see yourself in terms of being a role model or an inspiration?

Bradley: I think what everybody’s starting to understand is that every individual, the moment you walk out the door, is a role model for somebody. We all affect each other, our actions and the things we stand for and the things that we say (and don’t say), the things that we feel about ourselves that inform our action; they all add up to what is and what can be.

Filmmaker: Right now, we’re in a kind of limbo period. We’re recording this in June, and people are pretending like the pandemic [has] finished, when in fact it hasn’t, and much is up in the air. But I think this is going to go on and be such a significant film. Are you a manifester like Fox? From the moment you conceptualized this film, did you see this having the impact that it’s already had, and that it’s clearly going to have when it’s seen by lots of people?

Bradley: It’s a good question. When I really think about it, everything that I do is being pulled from my heart and my mind and my eyes—I’m always looking from the side of my brain, from the side of my eye. Somehow, it allows me to see the full picture and to not get too narrow in my focus. So, I never anticipated this because I didn’t anticipate a revolution happening (honestly) or COVID, but I know that my gut and my heart was in alignment with Fox’s, and I know that our guts and our hearts were in alignment with millions of other people in the country. That was our guide, and it seems that that guide is leading us to the right place. I hope.