Back to selection

Back to selection

“You Can’t DM People on 4chan”: Arthur Jones and Giorgio Angelini on Pepe the Frog Documentary Feels Good Man

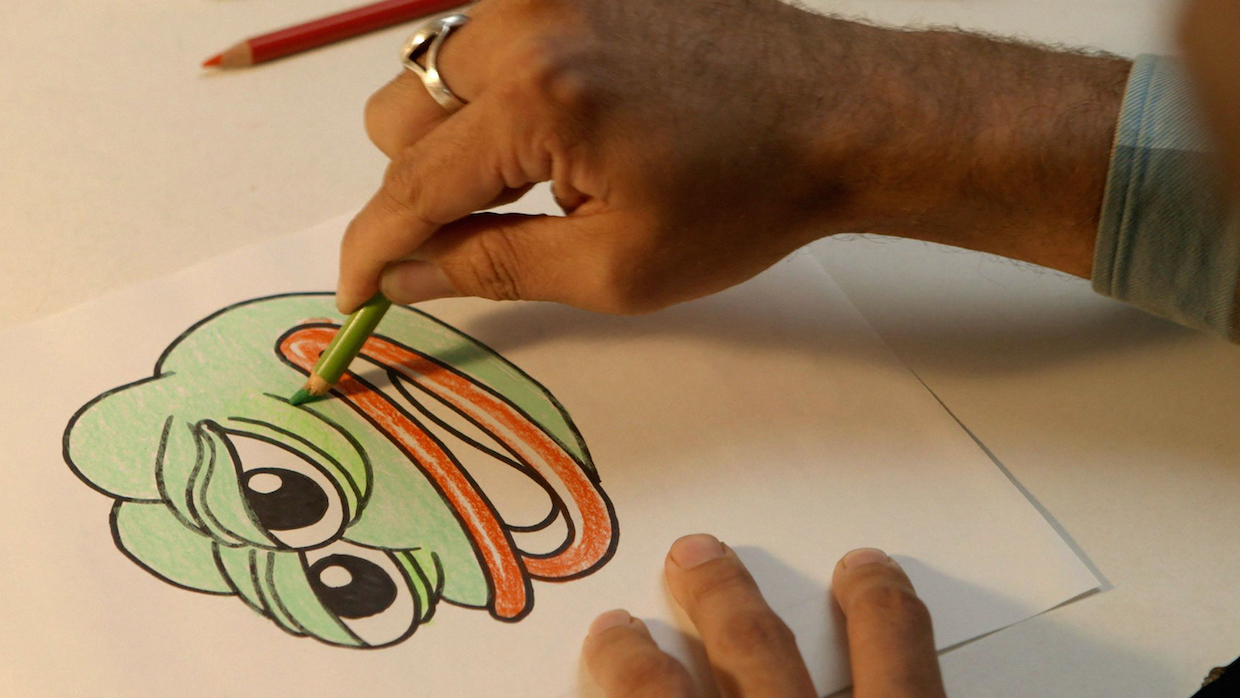

Feels Good Man (photo by Kurt Keppeler)

Feels Good Man (photo by Kurt Keppeler) “Pepe the Frog,” an anthropomorphized stoner, originated in the 2006 comic book, Boy’s Club, by artist Matt Furie. Like most amphibious beings who take an interest in cannabis accoutrements, Pepe is innocent enough, hanging out with his roommates and being an all around chill dude. Who could ever mistake Pepe for being something malicious? And how in the world could he ever be associated with (and co-opted by) the rising Alt-Right movement?

Pepe’s unfortunate journey from kid-friendly, zen bro to sinister symbol of hatred and domestic terrorism—jointly Google “Pepe the Frog” and “9/11” if you dare—is the basis for Arthur Jones’s debut feature, Feels Good Man, a documentary that follows Furie’s journey to reclaiming his creation. Showing us in uncomfortable detail just how the hell we got to this point, Feels Good Man chronicles the descent Pepe unwillingly took from the world of 4chan message boards to being the inspiration troubled youths needed to carry out violent acts of murder.

It’s not all doom and gloom, however. While you might still unwillingly come across memes of Pepe in various forms of evil dictatorship (sometimes being shared by evil demagogues themselves) on social media, various campaigns to make Pepe “good again” have proven successful, leading Furie to acknowledge and embrace his creation once more. At its heart, Feels Good Man is about an artist’s coming-to-terms with his symbol of hatred and being driven to reverse-engineer the madness.

After having its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival (where it received the U.S. Documentary Special Jury Award for Emerging Filmmaker), Feels Good Man premiered on digital platforms last week. I spoke with Jones and producer Giorgio Angelini about working with Matt Furie, their relationship to social media since marketing the film widely, and how the rise of conspiracy theorist groups like QAnon have frighteningly entered into the mainstream.

Filmmaker: Given that Feels Good Man is centered by and grounded in animation (both pre-existing and original), I wanted to ask if you both come from a background in the fine arts yourselves.

Jones: We come to filmmaking through different disciplines, with Giorgio being an architect, a restaurateur and a musician, and I being a graphic designer and animator. Before making Feels Good Man (my first feature), I had previously worked on a few friends’ documentaries (Michael Stabile’s Seed Money: The Chuck Holmes Story and Amy Scott’s Hal) and that’s how I caught the “documentary bug.” Around this time, Giorgio was directing a feature documentary, Owned: A Tale of Two Americas, about housing policy in a post-war America, and I was hired to craft some animation on the project. That’s how Giorgio and I met.

Angelini: We come from a multidisciplinary background within the creative arts, and Feels Good Man struck us as an opportunity to create something that serves as both journalism and an opportunity to move the documentary form forward.

Filmmaker: Had you been looking to make a film about the toxicity found in internet culture and, subsequently, Pepe the Frog became the central focus? Or did you already know Matt Furie and thought he would make for a fascinating subject?

Jones: A combination of both. I was a fan of Pepe before he became an internet meme. I had bought Boy’s Club comics back in the day and was more generally a fan of indie comics, and that’s how I initially befriended Matt. I enjoyed his artwork and thought he was a sweet, thoughtful, funny dude. I wasn’t necessarily looking to make a film about him, but I was looking to collaborate in some way, initially on a cartoon project. We were kicking around a bunch of ideas, but it kept [getting stalled], in part because the negative baggage associated with Pepe was too much for us to overcome. We pitched ideas to a variety of places and everyone was like, “I don’t know, Pepe has a lot of negative baggage to him.” All the while, I kept working in motion graphics and documentary films.

One day it occurred to me to try making a documentary about the issue. This really became clear post-Charlottesville’s Unite the Right rally in 2017, as I then felt a real sense of purpose to make something that would cut through the cultural static. From previously working with Giorgio, I knew that he had the same intention. The events at Charlottesville affected us in a pretty visceral way, and the “story of Pepe” subsequently became an important story to tell as it was, yes, about this “stoned cartoon frog,” while also speaking to the cultural moment in a relatable way. This angle felt like it could prove more effective than the making of a general “survey film” about the Alt-Right.

Angelini: We love any opportunity to tell an incredibly specific and eccentric story while simultaneously telling a much broader one about the culture-at-large. That’s the best way to get people to understand. Sure, you could do a “Ken Burns style” survey project (which are special in their own right) but this film offered a unique opportunity to tell an important story in a relevant way. There’s something about Matt, as a character, that feels very relatable. I think one of his friends in the film, Skinner, even says something like, “of all of our friends this could happen to, of course it happens to you.”

Jones: “This could only happen to you.”

Angelini: That’s right. And it’s true! Matt is a lovable guy, he’s innocent and naive in a way, and because of that, he offers the audience an incredible lens through which to experience these trials and tribulations. It’s been rewarding seeing how people have connected with Matt through the film. Certainly, film is subjective, and some audiences have been rather “take it or leave it” with Matt, but that’s the case with any project.

Filmmaker: Upon agreeing to participate, did Matt have any demands for you? Or was he hands-off and trusting in how you would tell his story?

Jones: He only had one demand and that was that the animation we were creating didn’t fucking suck. He didn’t want the animation to be the “standard documentary animation” that’s used to fill in a story gap or fill in the narrative; he wanted it to stand on its own. He also wanted Pepe to be represented in the way that the character initially was in the Boy’s Club comics. But other than that, Matt wanted us to make the decisions we felt were right for the film.

I think it was an uncomfortable process for him, as he’s a very private person and most comfortable in his studio, drawing. And obviously, making a film about him was not going to be that. I think Matt had a number of bad experiences over the years with journalists telling his story and felt that if someone else was going to tell it, it needed to be someone he was close to. That’s why he trusted us. That being said, he has a complicated relationship with the movie and deserves to have a complicated relationship with it. He likes the movie, but there are parts of it that make him feel uncomfortable, and that’s understandable.

Filmmaker: Several of those animated sequences mimic the animated style of Matt (and, in effect, the likeness of Pepe the Frog). Did you work with him on storyboarding those out? Or did he give you his blessing to run wild with it?

Angelini: That was one of the earliest conversations Arthur and I had, of first figuring out what percentage of the film would consist of animation. From the very beginning the idea was that the film had to canonize Pepe within these animations, because there are so many other memed cartoon characters (like SpongeBob SquarePants!) or even historically, growing up, I’m sure you saw those Calvin and Hobbes stickers where they’re pissing on a Ford or Chevy or whatever else?

Filmmaker: Yes.

Angelini: Everyone knew upon seeing those animations that they were bootlegs, that those weren’t actually from cartoonist Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes. But each of these cartoon characters have machinery behind them that reinforce the artist’s intention. Matt, and by extension Boy’s Club, didn’t have that luxury of audience familiarity. And so our film needed to canonize Pepe so that, once and for all, we could reverse-engineer the collective consciousness of Pepe and say, “No, this is Pepe’s origin story and this is where he’s from. Any derivation of that just is what it is.”

Jones: The storyboard process was pretty unique. Sometimes they would be taken from Matt’s comics and I would trace them and elaborate on certain scenes. And then sometimes (if we were really trying to underline some sort of cultural point) we would craft a storyboard and then kick it over to Matt to draw Pepe into it. He can obviously draw Pepe like no one else. It’s his character!

Filmmaker: Pepe originated in an era of slow dial-up internet, annoying pop-up ads and the proliferation of MySpace. Your film tries to capture that digital oasis we might have once described as the “wild, wild west.” There’s an analog feel to much of the first half of the film and I’m curious how you came up with getting that across to the viewer.

Angelini: Navigating the cultural moment of the film (and how we now talk about and promote it) has been interesting, especially when it comes to getting the word out via social media. We launched a TikTok account recently and, having never been on TikTok before, it was all very new to me. Almost instantaneously, the younger Gen-Z kids (having not even seen the film yet) checked out the trailer and the entire comment thread was about how the film portrays a more innocent moment in the lifespan of the internet. There has already been an interesting generational divide where the younger generation understands that there was this prior moment in the internet’s history and I think they see the film as a harbinger of that experience.

Jones: It’s a good question for a few different reasons. When we were structuring the film, we definitely thought in terms of how to give the film “analog parts,” as that’s Matt’s world and his living in his studio (our composers, Ari Balouzian and Ryan Hope, even used organic instruments for the film’s score to further illustrate the analog identity). And then in thinking about how we would portray the internet, it was more about a world of digital crunchiness and of data breaking up.

In order to understand the rejection of “normies” that happened online in 2014 and 2015, we had to acknowledge the fracturing that was taking place amongst people who were extremely online. If you were interested in the internet back then, that was completely your identity. You were someone who was on 4chan all the time, but your mom and dad weren’t on the internet much. The internet was your place. In the same way someone might consider themselves a punk rocker, these people were on/of the internet. The “Normies Out” movement were these people rejecting all kinds of “non-internet” people.

The founder of 4chan, Christopher Poole, eventually left the site because he felt it was no longer a place of innocent creativity, and when I say “innocent,” I mean “naive.” A lot of the early stuff on 4chan was pretty terrible, but it represented somewhat of a cultural shift.

Filmmaker: The film features one of those 4chan frequenters, a young man by the name of Mills, living in a basement and spending his days very much “online.” Even though you blur out the faces of his family (whom he lives with), I was surprised by the access you were allowed. How did you find willing participants of the “Normies Out” crowd for the film? Did you search for them on 4chan/8chan and announce that you were making a documentary?

Jones: While we did search 4chan looking for someone to be featured in the film, it’s a difficult place to start a conversation because it’s anonymous and completely public. For example, you can’t DM people on 4chan. You have to essentially write them a public note, opening yourself up to communication that way. As it turns out, Mills was himself a meme within 4chan (you can find photographs of Mills being used as shared memes on particular 4chan message boards). I recognized him from those memes and discovered that he had his own YouTube channel where a number of videos had been archived. One of those videos (that had very few hits) was of Mills talking directly to his cell phone and the first line he says is, “what does Pepe mean to me?” That’s when I knew that he was going to be our guy.

From the very beginning of production, we wanted this story to be told from a primary perspective. We didn’t want to lazily cut to a journalist explaining 4chan to you. In order to understand 4chan, you needed to hear it from someone who really cared about Pepe as a character and felt that the role/connection to the character was a part of them, representing a personal symbol of their culture. That was important to us, and from there, we reached out to Mills in earnest and began a dialogue.

Filmmaker: You interview several academic scholars who have studied meme culture and other unsettling aspects regarding the darker side of the internet. These men and women offer additional context, of course, but as filmmakers, you essentially bring these memes to a broader, more relevant light.

Angelini: The concept of memes was created by Richard Dawkins in the 1970s as a very academic concept for how to explain culture through a biological and evolutionary lens. A British professor by the name of Susan Blackmore then literally wrote the book on memes, The Meme Machine, in 2000, and now, of course, we have this internet version of what we consider memes. And just by accident, our inclusion of author John Michael Greer came to us through someone who had listened to an interview of mine when I was promoting Owned. I had mentioned that we were working on this film about Pepe and the listener recommended that we reach out to this occultist, John Michael Greer. It took a real wizard and archbishop of the druid order to be able to explain our story in the most salient way!

Jones: The study of memetics or, as John Michael Greer discusses in the film, the study of meme magic are really about people making an effort to talk about how people’s personal imaginations subsequently move out into culture, affecting the mass mind that any society projects onto itself. In every single interview we did for the film, we would bluntly ask, “why Pepe?” No one could really answer that question because there’s something about it that’s completely baffling. We wanted to have a way to talk about that in the film. John and Susan gave us the ability to navigate these bigger ideas in a way where the viewer can decide for themselves whether they agree with each.

Filmmaker: Once the film was announced for Sundance and you had a website created for the film, were you following any online chatter surrounding it? In a strange way, any online discussion of your film adds an additional layer to the power and allure of Pepe.

Jones: We’ve been pleasantly surprised by how positive the reaction to the film has been. Everyone asks us about worrying about the negative possibilities of it all, but, personally, I’ve “closed the laptop” on 4chan. I have not looked at 4chan since we’ve finished the film. As we’ve migrated promotion of the film onto social media, it’s been interesting to see how the undercurrents in social media have changed even since we finished the film back in December. Pepe is used on Twitch now in a totally different way! He’s being used as he originally was, as a reaction image. People use it in Twitch threads as a reaction image in a way that (for the most part) is baggage-free. He’s used on TikTok in a pretty baggage free-way too. We could not have predicted that when we made the film several months prior. The internet continues to shift and change and that’s just the way it is.

Angelini: It’s been both terrifying and rewarding to put this film out in the world, at least based on seeing viewers’ responses to the trailer. There was a very predictable response from the 4chan contingency (which you can read via the comments of our trailer on YouTube). But it’s also been interesting to see how each social media platform has its own contingency, like Facebook…

Jones: It’s the worst. Facebook is the worst.

Angelini: Yeah, but Instagram has an interesting mix of Gen-X and millennials who are very internet savvy, who may be into comics and understand what this film could mean to them on a personal level. It’s a film about their generation that’s being spoken about in a way it hasn’t before. The really rewarding aspect has been observing the TikTok kids and Gen-Z kids instantaneously “get” (from just the trailer) what this film is and isn’t about. As you might imagine, some see the image of Pepe and immediately recoil. It’s been heartening to see that kind of response being very minimal, that people are giving the film the benefit of the doubt.

Filmmaker: It’s true that the world has definitely changed since you finished the film last December. QAnon has crossed over into the mainstream, infiltrating “normies’” Facebook newsfeeds with hashtags like #SaveTheChildren and #Plandemic. Even the Wachowskis had to recently come out and say “please stop using the term ‘red pill’ from our Matrix franchise to describe your strange movement.” Has it been weird following our further decline into this online world of vitriol as you await the wider release of your movie?

Angelini: So, we’re actually going to be doing the QAnon Anonymous podcast soon, as (fortunately and unfortunately) the film’s relevancy has only grown. The meme magic behind Pepe has only intensified with the rise of QAnon. QAnon started off as a joke on 4chan and it’s now basically become the body politic of the Republican Party.

Filmmaker: Some QAnon followers may even be headed to Congress soon.

Angelini: Yeah, Laura Loomer just won her primary in Florida and Marjorie Taylor Greene won her own in Georgia. And then you have Trump’s former Director of National Intelligence, John Ratcliffe, who is also an avowed QAnon dude.

Jones: While it’s considered niche message board stuff, it’s now trickling out into the mainstream and the Republican Party isn’t doing anything to fight against the insanity. In fact, they’re actually emboldening it. Our movie is ultimately about media literacy. It’s about recognizing a troll when there’s a troll in front of you, and then also just understanding that the troll is not going away. This is a story about a stoned cartoon frog, yes, but it tells a much larger truth about what’s currently happening in America.

Angelini: What QAnon and the co-opting of Pepe represent is this pernicious trend that the commoditized internet experience has brought upon the culture-at-large. It’s infiltrated the culture and placed its realities onto our collective understanding of what is real and what is not. In this moment of dissonance, the real predators get to succeed. You have the Alex Joneses of the world (and whoever the heck Q is) succeeding in this particular moment, where being nihilistic and cynical and trolly used to exist and flourish online but is now flourishing in real life.

Our film is a rejection of that notion. We cannot build a society on these impulses. It doesn’t work. COVID-19 is a perfect, unfortunate example of how it doesn’t work. I hope that people who watch the film come away with an understanding that you shouldn’t let the internet shame you out of your capacity for empathy and understanding. Never let it control you in that way. You have to remember to, as Matt might say, “go outside, take a walk, be with nature for a minute.”