Back to selection

Back to selection

“They Live and Breathe Video, So We Just Completely Fit in with the Fixtures”: Hrafnhildur Gunnarsdóttir on her DOC NYC-debuting The Vasulka Effect

The Vasulka Effect

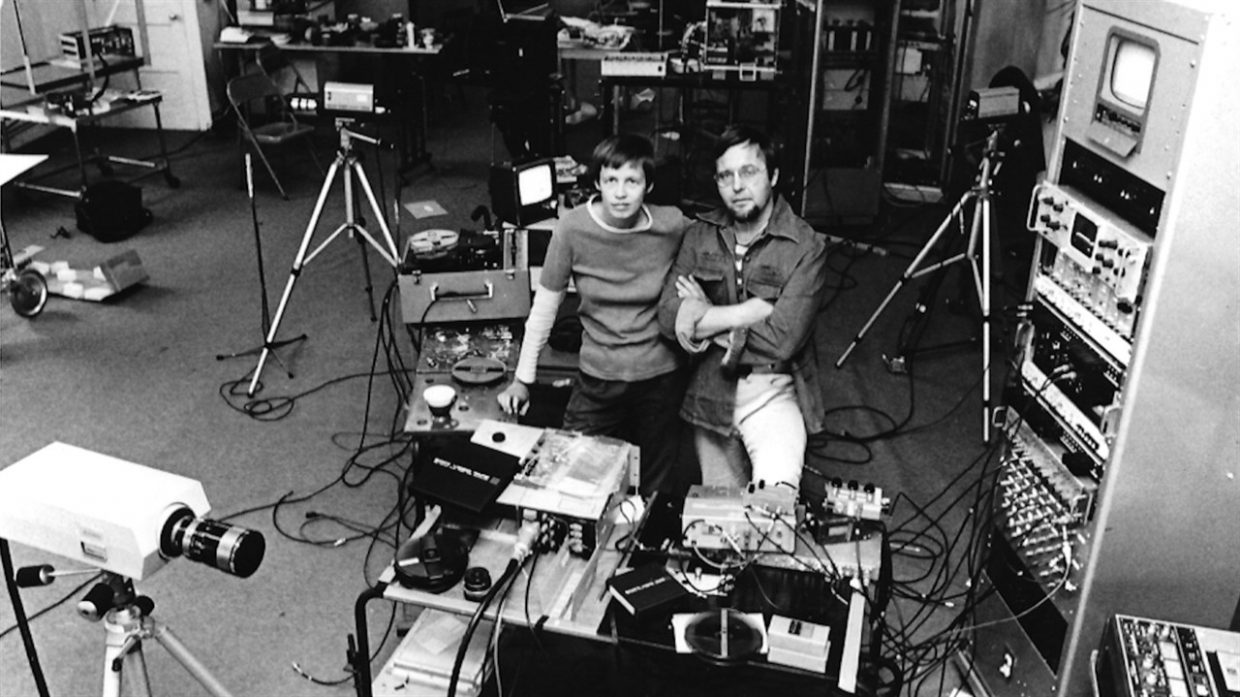

The Vasulka Effect As a New Yorker who has long prided my ability to namecheck most of the experimental art pioneers of the 1960s, I’m embarrassed to say I’d never heard of Steina and Woody Vasulka before watching Hrafnhildur Gunnarsdóttir’s The Vasulka Effect. Sure, I knew of The Kitchen, the legendary performance space the couple founded in 1971. And of course I was familiar with the work of the sound and visual visionaries that the Soho (now West Chelsea) institution provided a platform for — from Philip Glass and Laurie Anderson to Nam June Paik and Bill Viola. I’d just never connected a classically-trained Icelandic violinist and a Czech with a background in engineering — refugees from the Soviet takeover of Czechoslovakia — to the birth of it all.

Fortunately, The Vasulka Effect, virtually premiering at DOC NYC (November 11-19), remedied this knowledge gap for me. The film not only showcases a wealth of archival materials, including Woody’s video of Jimi Hendrix performing at Fillmore East and footage of their raucous parties with the Factory family, but also dives into their later creations. (Woody passed away in December 2019, and Steina has since turned to interactive installations. She’s also been a force behind The Vasulka Chamber in Iceland and The Vasulka Archive in the Czech Republic, founded in 2014 and 2016, respectively.) The result is an exhaustive portrait of two fearless boundary-busters forever obsessed with melding abstract imagination with concrete technology. And, in their retirement in Santa Fe, with the grind of meeting financial obligations and securing their rightful place in art history.

Filmmaker managed to catch up with the film’s Icelandic director, who likewise hadn’t heard of her iconic countrywoman until arriving on the West Coast to study, a week before the doc’s US debut.

Filmmaker: So how did you first meet the Vasulkas and ultimately decide to do a documentary about them?

Gunnarsdóttir: It’s actually a funny story. I studied in California, both at CCAC (now CCA) and later at the San Francisco Art Institute. It came up two or three times that my teachers assumed I was there to study video art, and that I was surely on track to become a video artist. Usually it was after them finding out I was from Iceland.

When I asked why they’d thought so, they told me they assumed I had been inspired by this great video artist, Steina Vasulka. I had no idea who she was. I was studying photography and some film, and eventually I did a few courses in video art. Then I worked for Video Free America, and Skip and Joanne Kelly also ran New American Makers, which was a video art screening series. The West Coast answer to The Kitchen, if you will. It was there that I met Steina, and we became acquainted. I started following her and got to know their art. I soon realized how important she was in the American art scene — and also Woody, of course. As I was unhappy that Icelanders did not know her, I did a small piece for television in 1992 about her and her art. After that we got to know each other better.

So I would call her and meet her if she was in San Francisco, where I lived until 2001, and then in Iceland. On a road trip in 2013 I decided to visit them in Santa Fe. At the time they were busy with figuring out what to do with their huge archive. And they were also in not so great financial shape. I was surprised that such important artists would be having such serious financial problems. That gave me the idea to film them over the next few years to see how everything would pan out.

For one thing, I was interested in seeing if they would manage to secure a safe place for their archive. Also, if they would die unknown and in poverty, or not able to continue doing their work. I pitched the project to the Icelandic Film Fund and then asked my colleague, producer Margrét Jónasdóttir, to co-produce. Eventually I got a yes from both. The next year I received a scriptwriting grant and started filming.

Filmmaker: I’m guessing that Steina might now be better known in Iceland than here in the States, so was it just easier to get Icelandic financing? Did you even try for US funding?

Gunnarsdóttir: Steina is actually better known in the art circles in the US — at least in the East and West Coast circles. But people here do know her a little better than they did before. We didn’t end up trying for US funding. The finance situation is quite a bit different than it is in Europe, and we managed to fully finance from here.

Filmmaker: What was it like filming subjects who had spent their entire careers exploring the camera’s potential? Did they attempt to participate in the production or editing, or were they strictly hands off?

Gunnarsdóttir: Both of them were interested in my cameras, and of course the sound recording. Woody was in more of a performance mode, ready to dance with the camera whenever we had it on. Steina was quite shocked that we were filming sound and video separately and told us they had invented equipment in the ’60s that recorded audio and sound in the same place!

Steina also made me make her two promises. One, that she would get all the footage we filmed; and two, that I would also make her a clean version without any music. Which I did promise. She will get all the footage, but she has not asked again about the clean version, which means that she likes the composition. Steina´s biggest issue is only about the length. She is not interested in TV or feature-length running times.

Filmmaker: How much archival footage did you have to sift through, and how long did that process take?

Gunnarsdóttir: Oh, that was the most difficult part. Our editor Jakob Halldórsson did a great job finding the archival bits once I let him loose with the material. We had ten discs, eight terabytes each, so it was a lot. I called it Pandora’s Box! I had no idea what I would find. We could have made several films out of the archival material. The film took about a year to edit. Which was unusually long (at least by Icelandic standards. I like to take a long time, though my producer does not!)

Filmmaker: I’m curious about the parameters the couple set with regards to filming. You shot almost exclusively at their house in Santa Fe, and even capture a naked Woody in the shower, but what particular aspects of their insular life were still off limits?

Gunnarsdóttir: Nothing was really off limits. The house is like a workshop studio, with no normal household stuff — not even a couch. They live and breathe video, so we just completely fit in with the fixtures. Woody was not very controlling, but his mental capacity was changing, declining slowly during the filming process. Steina is not codependent, so she was not about to restrict our filming. We also totally crossed the line, as she wanted us to help them numerous times. I have washed the floors of their house in Agua Fria and cleaned the kitchen cabinets. And we have helped them with applications and video editing. So, yeah, nothing was off limits.

Of course, that had to do with her trusting me and the sound guy Árni Benediktsson, who is the former manager of The Sugarcubes. When I first showed up with him at Steina’s family house in Iceland she looked at him with these stinging eyes and asked, “Hverra manna ertu?” It’s a very Icelandic question, meaning, “Of what people are you?” As he told her who his father and mother had been I could see her face changing. When he was done she said, “Aha! So the last time I saw you I held you in my arms and you were wearing diapers.” Her parents had been drinking buddies with his parents. It was real camaraderie working on this film.