Back to selection

Back to selection

THE FOG OF WAR

It was just after 6:30 p.m. in a small village near the Pakistan border when Pat Tillman heard the first explosion. Instincts had always played a big part in his life — at this moment they would take over. Aware that his friends and brother Kevin were back where the explosions and gunfire were coming from, he headed up to a better vantage point, calling on Private Bryan O’Neal to take his side. Secured behind a pair of low boulders, Tillman, O’Neal and an Afghan solider had a clear view of the exit of the narrow gorge their serial had just passed through. Their fellow Army Rangers should emerge through it at any moment.

Minutes later their mates appeared, pumping with adrenaline but little common sense. Seeing three figures above them about 90 yards away, four Rangers in a ground mobility vehicle began to open fire, spraying round after round on the boulder location. The Afghan solider was fatally shot, O’Neal dropped his weapon and began to pray, but Tillman tried to stay in the moment, tossing a smoke grenade toward his fellow Rangers to prove they were shooting at friendlies. Author Jon Krakauer in his book Where Men Win Glory: The Odyssey of Pat Tillman recounts what follows:

O’Neal said he “heard a hissing sound, it was a purple smoke grenade that Pat had set off. The fire then stopped, and Pat and I got up…. We both thought everything was good at the time.” It was however, just a momentary pause in the onslaught. Within moments the Rangers resumed shooting.

Ten or 15 seconds later, O’Neal noticed that Tillman’s voice took on a distinctly different tone — Pat had “a cry in his call” is how O’Neal described it — and O’Neal assumed Tillman had been hit. Tillman, it turned out, had taken one or more shots to the chest plate of his body armor — sharp blows that would have felt like a jackhammer striking his sternum. Astounded that his fellow Rangers would act so recklessly, he began to holler at the top of his lungs, “What are you shooting at? I’m Pat Tillman! I’m Pat fucking TILLMAN!” His angry disbelieving cries, however, had no discernible effect on the gunfire at Tillman from less than 120 feet… the distance from home plate to second base on a baseball diamond.

Seconds after his final words Pat Tillman was dead. The fratricide that occurred on April 22, 2004, would not be known by the public, or more importantly, Tillman’s family for more than a month. What would follow would be a despicable version of military omertà that began with Pat’s fellow Rangers and reached all the way to the White House. As filmmaker Amir Bar-Lev (My Kid Could Paint That) chronicles in his latest documentary, The Tillman Story, it would be Pat’s mother Mary “Dannie” Tillman who would lead her family through pages of redacted documents and military double-talk to find some semblance of the truth. All the while a nation built up the mystique of the battlefield hero it wanted Tillman to be.

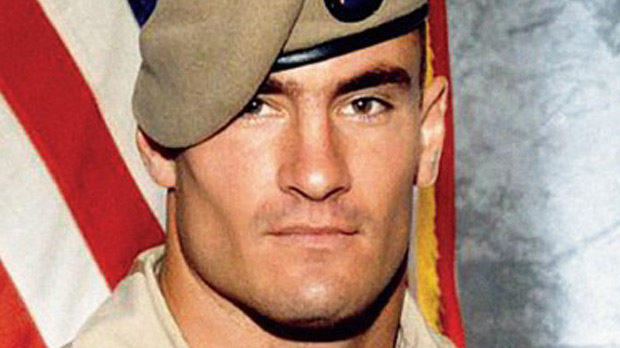

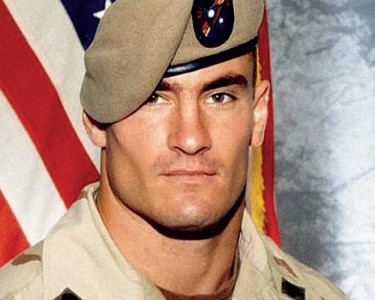

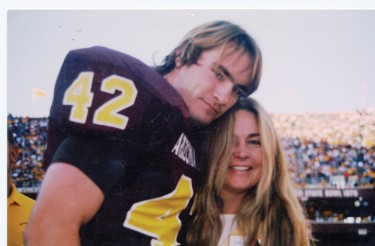

To sports fans Pat Tillman was an overachieving football star who, with Arizona State and then for four seasons with the Arizona Cardinals, played with a drive that amazed his coaches and fellow teammates. At only 5’11” and 202 pounds, Tillman was undersized for the NFL, but his tenacious approach to the game and hard-hitting tackles as a strong safety in the backfield quickly made him a fan favorite. However Tillman was not your typical jock. He read poetry, climbed trees and ran marathons in the off-season, and he didn’t even have a flashy car. (He would ride to practice on a bicycle.)

After the attacks of 9/11, Tillman began to rethink his priorities. He decided to pass on a $3.6 million contract with the Cardinals and enlist in the elite Army Rangers unit with his brother Kevin in 2002. Aware that his notoriety could be abused by the military’s public relations department, Tillman did not grant any interviews and even wrote in a military document that he did not want the military involved in his burial if he were to be killed in action. But Tillman would ultimately have no control over how he would be memorialized. Original reports on Tillman’s death were that he was killed saving his platoon from insurgents. Based on that narrative he was awarded the Silver Star. Soon, songs were being written about Tillman, and a bronze statue of him was erected outside Sun Devil Stadium. There were even conspiracy theories about his death. The Bush administration had finally gotten a poster boy for the war.

Bar-Lev spent three years filming the Tillman family, beginning shortly after the seventh unfruitful investigation by the military but before a scheduled Congressional hearing. Mixing archival footage with beautiful cinematography from d.p.s Igor Martinovic (Man on Wire) and Sean Kirby (Zoo), the film deconstructs Tillman’s heroic military aura and tells the tale of a mother searching for her own sense of closure.

The Weinstein Company will release The Tillman Story August 20.

Why did you change the film’s original title, I’m Pat Fucking Tillman? We wanted to originally call it I’m Pat Fucking Tillman but there were a couple of problems with that, not the least of which was that people kept thinking the film was [titled] I’m Fucking Pat Tillman. [laughs]

Not many know that those were his last words before being killed. No one knew and it’s really powerful when you get to that point in the film, but people don’t get it leading up. It also limits the audience if you’re being realistic about it, and there’s an opportunity with this film to reach audiences that normally don’t watch documentaries.

Was the family okay with the original title? They liked that title. [laughs] What’s most powerful about that old title, and it holds true as the line in the film, is there’s a very supernatural foreshadowing on the part of Pat Tillman. One of the projects involved in the film is taking him down off the mythological pedestal, but at the same time he has a couple of moments that in hindsight read as uncannily prescient. One of them is that his last words, “I’m Pat fucking Tillman,” work on a couple of levels. The most obvious level is he was trying to tell his platoonmates who were shooting at him from 40 meters away that he was a friendly. And then the second level is he’s swearing [which all the Tillmans do often]. But the third level, the prescient level, is it functions as a call from the dead to the future where he would have to insist on who he actually was. It’s almost a call from beyond to say, I’m not this person, I’m just Pat Tillman. That’s why I liked it as a title because immediately, less than a minute after he said those words, that mythology and the lying began. And not just from the soldiers on the ground or the higher ups back at base, but all of us, the media, the culture, everybody. But The Tillman Story I’ve come to like more. I think it’s the right title because it’s a film more about a story than it is about Pat.

What interested you about Pat? Did you follow him in his football days? No. I just knew the bare facts that everybody knows, about the cover-up and the friendly fire. What hooked us, including my partner John [Battsek], is when we started to get to know the family we understood the family was more committed to demythologizing Pat than even we were at that point. There were all of these Paul Bunyan-esque ideas about Pat out there, and the family had felt they lost him twice, once in death and the second time to myth. They were very interested in the film rectifying that.

There were seven investigations done into the death of Pat by the military. At what number did you come into their lives? We came in just before the congressional hearing.

How did you get in with the family? Painstakingly. [laughs]

Does it start with an e-mail, or through someone who knows the family? Both of those things and a lot more hectoring on our part. One of the most likable things about this family is that they have a very healthy sense of what’s public and what’s private in a time where that sense is sorely lacking. They had been turning down people left and right who want to tell this story.

But Dannie [Tillman] had written a book, and Jon Krakauer was writing his book while you were making the film. Were there conversations around why a movie even had to be made? It was sort of like that. They had been sorely disappointed in the media so far and they wanted to make sure we weren’t carrying on in the same superficial vein. The main thing we had to do was convince them that we were going to be something different. And you know, My Kid Could Paint That is a funny calling card, right? I had to sheepishly hand over that DVD and say, “Ah, unless the dad was secretly playing football you have nothing to worry about from me.” But in the end they put their trust in us and we’re extremely honored by that. We felt a tremendous obligation to get the story right and Dannie’s book did a lot of the work for us. Her book is kind of the script for the film in some ways. So we worked really close with them. Pat’s brother Kevin isn’t in the film but he helped at key points, made introductions. Having the stamp of approval from this family was essential to making the film. Anybody we called they would say, “I have to get back to you.” And we knew they were calling the Tillmans to check us out.

Did you ever ask Kevin if he would go on camera? Of course. But he’s a very private guy and I totally respect that. This family isn’t compelled to get on camera and talk about how much they love Pat, and that’s extraordinarily admirable. I mean, I asked them about the moment [Pat was killed] and invariably each one of them said, “I’m not going to go into that.” And Kevin has been asked to do everything from interviews in every magazine you can imagine to fucking American Gladiators — really disrespectful stuff, and he turned them all down. But he went to Congress and then decided to go public with his thoughts, and it went absolutely nowhere. He concluded, “I’m not going to do it anymore, I put myself out there, nothing came of it.” So by the time we came around he was resolute, and I admire that.

Talk about the look of the film. You had Igor Martinovic and Sean Kirby as your d.p.s. Were you thinking of a certain look for the film early on? I was reacting in part to the grittiness of my last two films. I wanted to do something different, and I knew there would be very little vérité in this film and so the visual element had to be found in a different storytelling device. We were very lucky to have the film financed up front by A&E Indie so we got indulgent. [laughs] I had this idea of lugging this dolly around everywhere we go so the indulgent part was a dolly and two cameras everywhere we went, the video camera and the film camera, because I wanted to shoot the B roll on Super 16. With the B roll we tried to create these tracking B roll shots; at one point we thought they would fit together and for a long time in the edit they did, kind of like The Wire style — a tracking shot with two cut points on either end and you’re just wiping off things. Late in the edit we backed off [of this device], but you see it in the credit sequence.

What sort of research did you do for the film? One of the more interesting elements of the research was this conceptual scavenger hunt that we went on that involved pulling a lot of archival and responding to what we found. It broadened the film and then contracted it. The film was two and a half hours at one point. The first thing we did was collect every piece of news in any media about Pat Tillman — every book about him and all the songs about him. We gathered all of that and then we thought about what the recurring themes were, and one of the most prevalent was “The Greatest Generation.” Everybody associates Pat Tillman with The Greatest Generation, so then that lead us on this scavenger hunt. People saw 9/11 as a Pearl Harbor moment and after it happened there was this recurring theme in the American discourse about returning to a time of moral servitude, finally getting over the baby boomer years or the moral relativism years and returning to a time of collective purpose, and Pat Tillman seemed to embody that. Then we would come across something like the family being told on their first briefing that [Pat’s battle] was like the first scene in Saving Private Ryan. So again you have this World War II theme. We originally started the film with the first scene in Saving Private Ryan and that film became a motif. It was fun to do but it didn’t work — it was too far afield. I also did this in My Kid Could Paint That. Just pulling in all this stuff to get different ideas [on how to tell the story]. You spend a ton of money and you worry the hell out of your producer. He would ask, “Why do you want the red carpet to Band of Brothers?” That scared the shit out of him. But he understands that’s part of my process.

And then there’s the redacted documents given to the Tillmans and the reenactment video of the firefight the military made for them. I’m assuming you got all of that from the Tillmans? Yeah. But it’s kind of shocking because anyone can get that. You can actually buy [the video made by the military] on Amazon. Just search for Pat Tillman. This is the thing — a lot of what’s in our film anybody could have gotten. It shows how thinly stretched today’s journalists are. They don’t have the time and resources to do good journalism anymore. I mean the 3,500 pages of documents on Pat Tillman’s death you can download off a website. It’s public domain. And it’s amazing to read stuff that you’ve just downloaded that never made it to the press, shocking stuff. You feel like you’re along with Dannie in how maddening it must have been for the family to be staring at this stuff in black and white and to have it not reported. But the military has been adroit in getting their message picked up and repeated by the press.

This kind of parallels what went on with Jessica Lynch. There was a false story given to the public of what happened to her convoy and her rescue. And as you show, it so happens that Tillman was involved in her rescue. That was one of those unbelievable coincidences. That’s from that scavenger hunt I was talking about, the fact that Pat was present at the “rescue” of Jessica Lynch. He was stationed on the periphery of the operation, and he sensed that if he died they would do the same thing to him and he could be used the same way. This is the downfall of going from a two-and-a-half hour movie to 90 minutes. There’s so much that ended up on the cutting room floor that I hope to put into DVD extras. One example is they wrote on Pat’s autopsy report — and this is one of the things that drives Dannie Tillman crazy — “CPR administered,” and in the congressional hearings, they ask her, “Is there anything else you want us to look into?” And she says, “Yeah, it says on the field medical report that CPR was administered. My son wasn’t brought to the field hospital until 45 minutes after he was declared KOA and he didn’t have a head.” To hear her say her son didn’t have a head was so striking, and we shot her saying that, but it’s too complicated to put into a 90-minute movie. You have to explain why they put in that they administered CPR. Because if a person comes into the hospital alive you’re allowed by regulations to burn their uniform, if they’re dead it becomes evidence, but they did burn everything Pat wore and had on him that day.

Did you try to interview the guys in the platoon who shot at Tillman? Yeah, but they wouldn’t speak.

Have they ever spoken about that day outside of the interviews with the military? No.

In your research, did you explore the conspiracy theories that are out there, like that Tillman was assassinated? Absolutely. The myths about Pat Tillman are shared on the right and left. The biggest, this idea that he was in contact with Noam Chomsky, of course, we ran that down and we interviewed the woman who was his go-between to Chomsky and she told us flat out, “No, there was no contact between Noam Chomsky and Pat Tillman.” She said, “The extent of the contact was that I happened to take a class with Noam Chomsky and I knew my friend Pat was a fan and so when he got out of the service I tried to broker a conversation between them.” And Chomsky had written one very quick e-mail at 4:00 in the morning saying something like, “I might be open to it, have him call me.” That’s it. And that has become Paul Bunyan-ized into this idea that they were in cahoots. It’s all part of our inability to separate our movies from our reality.

And this kind of goes on what I get asked a lot at Q&As, which is, “Has the military tried to silence you? Or are you worried?” And I say, “The military doesn’t have to put a bullet in my mailbox; the reality is all the military needs to do to dominate this debate is what they’re great at, which is having a team of PR people. This is not as nefarious as the Hollywood version of how the government works. What I’ve come to learn while making this movie is what the military has that’s a stronger part of their arsenal than special ops is a team of publicists. All that matters is CBS, NBC and the rest getting the right sound bite into their mix, and they do that very readily.”

Do you think the film will help the family get the answers they are looking for? I don’t know if I can answer that. The Tillmans have a lot more questions than answers, and they still to this day don’t really know what happened. Nobody really understands what happened that day, and there’s been no culpability on the second half of this tragedy, which is the higher ups trying to cover it up. Something that the family said early on was they were focused on the film helping ensure that this doesn’t happen again to others. I think that’s probably more their focus. I think, to borrow a football metaphor, they ran the ball 99 yards over four years time, they handed it off at the one-yard line to Congress and they fumbled it. I think you see in the film that [the family has] a sense of resignation. They’ve spent years with this and they’ve moving forward in a different way.

Do you think the film will help the family get the answers they are looking for? I don’t know if I can answer that. The Tillmans have a lot more questions than answers, and they still to this day don’t really know what happened. Nobody really understands what happened that day, and there’s been no culpability on the second half of this tragedy, which is the higher ups trying to cover it up. Something that the family said early on was they were focused on the film helping ensure that this doesn’t happen again to others. I think that’s probably more their focus. I think, to borrow a football metaphor, they ran the ball 99 yards over four years time, they handed it off at the one-yard line to Congress and they fumbled it. I think you see in the film that [the family has] a sense of resignation. They’ve spent years with this and they’ve moving forward in a different way.

In your eyes is Pat Tillman a hero? Absolutely. Without a doubt. But being involved in this story for three years I learned a lot about heroism and that “hero” has different definitions. It usually says more about the people calling someone else a hero than about the supposed hero, so I hope that’s in the film. We as a society have taken Pat Tillman’s heroism out of the story of Pat Tillman. It started with the military turning him into this John Wayne hero and pretending he had saved his platoon from the Taliban. But in fact what he did was by being an agnostic leaning toward atheist he saved Bryan O’Neal’s life — he told [O’Neal] to quit praying and get back into reality. That had to be taken out of the story, so his actual heroism was stripped from the story. But as a society at large we did the same thing the military did. We took his actual qualities and replaced them with the opposite, this square-jawed paragon of moral servitude who had an idea and stuck to it no matter what. This sort of Bush-era fantasy, but in fact he was the opposite. He always took something and looked at it from every direction. He would take a conviction that he would have and challenge it. That was a quality of his that we couldn’t accept as heroic so we had to replace it. He was absolutely a hero, but in none of the ways that he was made out to be.