Back to selection

Back to selection

“This Sometimes Happens, That Cameras Fall in Love”: Alexandre Koberidze on What Do We See When We Look At The Sky?

What Do We See When We Look at the Sky?

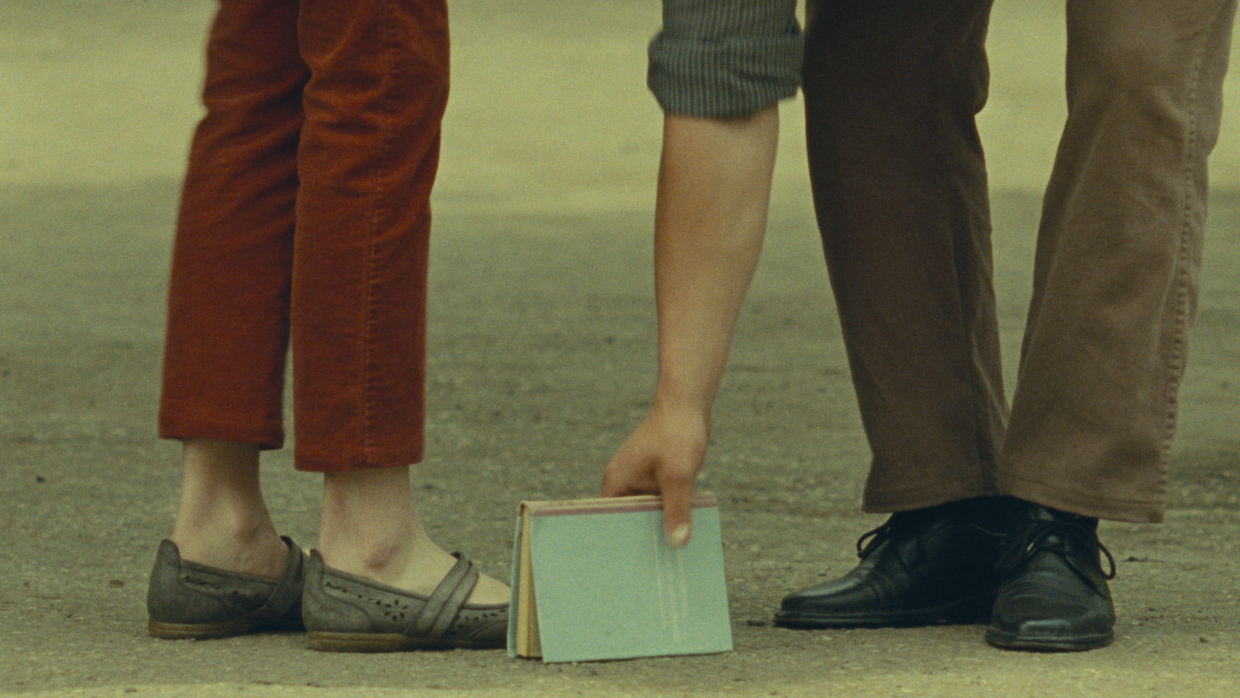

What Do We See When We Look at the Sky? Alexandre Koberidze’s camera is caught up in the day-to-day of the locals of Kutaisi, Georgia, before the meet-cute of main characters Giorgi (Georgi Bochorishvili) and Lisa (Ani Karseladze) draws its attention. The camera watches their shoes as they first stumble into each other, recollect their fallen books and dart off in the wrong directions before realizing the mistake, turning around and bumping into each other all over again. When the camera finally pans up to reveal their faces, it places the curse of the “evil eye” on the would-be lovers, who just scheduled their first date together. As a personified seedling, rain gutter, and security camera explain the curse to Lisa, Georgi can no longer recognize her. The wind is supposed to tell her that she can also no longer recognize him, but a large truck intercepts the gale carrying the message. So, they both show up to their first date, and, unable to recognize each other, leave thinking the other never showed up. Koberidze’s camera then re-concerns itself with the non-actor locals and anonymous actors mingling among them, unaware of the anti-romantic/romantic narrative they vacillate between being a part of and not. In What Do We See When We Look at the Sky?, Koberidze blends fiction and nonfiction, narrative and meta-narrative, film and digital, visual storytelling and exposition, into a surprising clarity, for his version of a fairy tale.

In Koberdize’s Kutaisi fairy tale, wild dogs follow soccer statistics, Argentina wins the World Cup and curses are cast, broken or protected by rings and amulets. But at the same time, his fairy tale is filled with reality: real-life people, friends, situations and voice-over interjections of Koberidze’s actual thoughts beyond the scope of the film. Experiencing this bizarre combination, I struggled to imagine Koberidze’s process. So, at a cafe on his last day at the New York Film Festival, I talked with him to demystify it. But in revealing some of his creative procedures, What Do We See When We Look at the Sky? loses none of its magic. For Koberidze, we experience this magic in our day-to-day. It is not apart from our reality, only a challenge to see, show and explain it to others—as his personified camera so wonderfully captures. What Do We See When We Look at the Sky? opens tomorrow in the US from MUBI.

Filmmaker: What does the opening quote [“‘These morons have never seen a raven,’ Guia A. thought, but you couldn’t notice anything on his face.”] reflect of the mood of What Do We See When We Look at the Sky?

Koberidze: There is no visible drama, at least in the acting, no dramatizations of the situations that happen. Another reason I picked this quote is that on one hand, it’s a writer from Kutaisi who was writing quite a lot about this town, and the moods he was creating were quite inspiring. But also this very quote is about experiencing very dramatic things but not showing [them] to others. That’s very much part of the film, although the reason for it is quite unknown. For me, it was that these characters didn’t want their personal or intimate problems, which are smaller than the problems we really have, they didn’t want to make them seem bigger, so they don’t show it.

Filmmaker: At the Q&A on Sunday, you mentioned that you wrote the film in novel form and only wrote it as a script to help raise funds. When shooting the film, did you refer back mostly to the novel then?

Koberidze: My idea was to write the script, then somehow forget it and get back to this novel. But it’s hard to work this way, because you write the script and it also becomes something precious even though it has no form and shape, which is interesting to me. I realized when we were almost shooting that I was stuck with this script, which I thought I had made just to make money but changed the film a lot. You share it with the cinematographer, the producer, then everybody has it and at some point it becomes too late to say, “No, no, no. This is not the film.” There is no huge difference between them, just little details.

Filmmaker: Despite having all these precious, pre-existing materials, you seem excited by any opportunity to throw them out or change them.

Koberidze: On the one hand, it’s really hard for me. There are certain things I want a particular way, and I try to follow my wish or desire to the very end. But on the other hand, I try to be open, to have blank spaces. Maybe I write a scene and another scene, but not a scene that connects them, I leave it open. Or maybe sometimes I don’t shoot a scene, presenting difficulty in the editing. This difficulty creates the necessity for creative decisions. When you don’t have a scene that you need, that’s when you start to think. Otherwise, you could just give the film to someone to edit. That’s why I edit by myself. I love editing, and I also love these difficulties, because that’s when I can start to play.

Filmmaker: I appreciate how much time you spend in a single day or night. You really feel the day and night cycles in the film.

Koberidze: It’s very interesting when you really start to think about it. We shot for ten days before the actual shooting with a small team, kind of like a documentary. Then I saw how things looked on that [16mm] camera in the night and in the day. I started to bring some scenes that were written for the day into the night and vice versa, because of the camera or material I shot on. I really liked how the 16mm looked at night when there’s not so much light in the darkness, because then it starts to have difficulties. It becomes somehow alive.

Filmmaker: About 20 minutes in, you ask the audience to close their eyes for 3 seconds, after which you switch to digital. The first time I saw the film, I didn’t realize that this is when you make the switch between formats, I thought it was just a switch from night to day and that you were queuing the curse of the “evil eye.” Why do you ask the audience to close their eyes for this transition?

Koberidze: I’m saying, now the magic will happen. How do we show it? It’s hard. It’s also a very personal thing—magical things are maybe private, so it’s hard to experience them with a group. Sometimes in the cinema, it’s good to close your eyes and be by yourself. Of course, I could have made some special effects, but I didn’t want to use these tools to make a change in the mind of the viewer. When you close your eyes you’re more concentrated, and I like the idea because then it starts again. Maybe you feel a little bit like a kid who starts a game with someone. You can join this game, this fairy tale.

Filmmaker: What if a viewer keeps their eyes open?

Koberidze: I think in the end it doesn’t matter. I don’t know what percentage of people are doing it. It’s like a virus: if you see people do it you do it too, and if nobody’s doing it you don’t. I think it depends on the screening.

Filmmaker: The couple at the center of the film are cursed by the “evil eye,” in other words by your camera observing them, which results in them becoming unrecognizable to each other. It takes for them being filmed by another camera, the film within the film, to break the curse. What does this say about how you feel about what film is capable of?

Koberidze: Generally, we know how much impact cinema has had on history, how it changed it, and how many good and bad things have happened. It’s easier to follow and discover bad things like propaganda and its impact. If we use this language of good and bad, which is probably not the right language to describe it, it’s really hard to follow the positive impacts—you don’t have anything to touch. But I strongly believe in the good because I have experienced it. Cinema has changed me very much. How I see, how I see people, how I treat people, how I think, is very much related to the films I’ve seen. There are films that I think, if I hadn’t seen them, I would be a very different person. So, when I think about myself, I think this definitely must have happened for other people. But it’s not only bad and good, film changes so many things.

Maybe ten years ago, I was in Finland in Helsinki. I’m a big fan of Aki Kaurismäki, that’s why I went, I went alone for New Year’s Eve, just to spend some time there. It was strange being there, because I was not sure if Aki Kaurismäki was showing me how Finland is, or if this place had become what he did to it. You don’t know when you’re there. I think it’s both, and I think that says a lot about the power of cinema.

Filmmaker: You’ve suggested that you fill your films with situations or relationships you wish you had in your real life.

Koberidze: For example, football. I’m not a football player, that would have been a dream, so I think this is one thing I compensate for, and I think I will continue to do more of that. But also, the general way of communicating, how people talk with each other, how they deal with problems, how and which decisions they make and the general rhythm, is sometimes, in this film, like I would desire to have around me, and that I don’t have. I don’t know how to create this in my real surroundings, or it’s impossible to—at least now, for me. But when you’re creating the world in a film, then you have this possibility, to have these moments that are like a dream.

Filmmaker: Did you used to play soccer, or dream of playing professionally?

Koberidze: I never played but I was dreaming of it always.

Filmmaker: But you watched?

Koberidze: I watched and played, but with friends. My dream would be to play big football in front of an audience. But when we play, nobody’s watching, and I can understand why, because it’s not beautiful.

Filmmaker: Why do you start the film with children leaving school and a series of greetings and goodbyes?

Koberidze: I was looking for a situation where the two people could meet coincidentally, but more than that it’s just a great joy to film children. I really enjoy it. I also wanted to introduce that this film is sometimes like a silent film. When I saw the school with this gate, I thought that would be the code: the kids were leaving school, and we would set it up almost like repeating one of the first films, Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory—but it’s not workers, it’s kids who are leaving the space where they have to be day to day. So, on one hand the kids, and on the other, an opportunity to say this is a silent film.

Filmmaker: Are you ever filming strangers guerilla-style, incognito around the city?

Koberidze: It’s different. When I made my previous film, Let the Summer Never Come Again, which I shot on a Sony Ericsson cell phone, I was sometimes hiding because I knew that it was impossible to recognize these people, because it was such low resolution. But on this film, everybody knew we were filming them. Some kids didn’t know at that very moment, but the school knew, the parents knew, and afterward we spoke with everybody. When we were shooting, for example, people watching football, we were telling people we were filming here, but had a rule that we don’t film the faces of people we don’t know, because it’s too private and serious for me. I have to have some understanding, or relation, or some reason to film someone’s face. It’s too much, it’s too big, it’s too much past and things that already have happened. If we film someone, either it’s part of the film and we know, or it’s kids. With kids, it’s easier because they don’t have this past. And if they’re ok and their parents are ok, I don’t have a bad feeling about filming them. But with grown-ups, it’s harder.

Filmmaker: Did you have any trouble filming in Kusaiti? I’m thinking of trying to film something like this in LA, and every location knowing they can charge you a certain amount of money to do so.

Koberidze: No we had big freedom. We had one bad story, but it was a one in a million thing. Normally there are almost no films made in Kusaiti, and this part of Georgia is also known for people who are very welcoming and easygoing, so it was quite comfortable to shoot. The only question we were getting was, “Do you need some help?” [laughs]

Filmmaker: When Giorgi realizes he can no longer see his reflection, the audience learns about this and his reaction through the voiceover narration, not through the visuals. We do see him pick up the mirror on the piano, as reported by the narration, but we don’t see anything else as it is described. Can you talk about the relationship between narration and image, and what you decide not to not show?

Koberidze: It was deliberate that I did not show his reaction, because I also don’t know how someone would react to not being able to see their reflection. [laughs] Also, when I have seen how people react to things like this in films, I go, “Oh, come on!” Nobody can say how somebody would react. I don’t believe that somebody would shout, or jump one step back. Maybe, yes, but I want to believe that it would be something else. But also, I just want to leave it to fantasy.

Filmmaker: When you first dreamt of being a filmmaker, did you ever imagine your films would look like they do now?

Koberidze: Not at all. Even this film, when I was starting, I couldn’t imagine it. It was quite a surprise for me, even though it follows a script and stuff like this. This was the same case with the previous film. Every time! If I speak about how I was thinking 15 years ago, I didn’t have the fantasy of this kind of film yet. Anyways, it’s hard for me to understand what kind of film this is because I just see the work. I can’t understand it, I can’t watch it as a film. But still, I think 10 or 15 years ago, if you would have asked me, I would have answered something quite wrong. [laughs]

Filmmaker: 10 or 15 years ago, what did your dream film look like?

Koberidze: 15 years ago I was thinking about a film where a camera falls in love with an actress and starts to zoom on her, making her sharp or out of focus, stuff like this. Because this is quite annoying for the camera operators, they bring it to someone who repairs cameras, and he says, “This sometimes happens, that cameras fall in love.” That was the film I was thinking to make, and maybe, luckily, I did not. [laughs]