Back to selection

Back to selection

“The Film is One Big Conversation. I Could’ve Cut it Ten Different Ways and It Would Still Be the Same Conversation”: Sterlin Harjo on His Netflix Doc Love and Fury

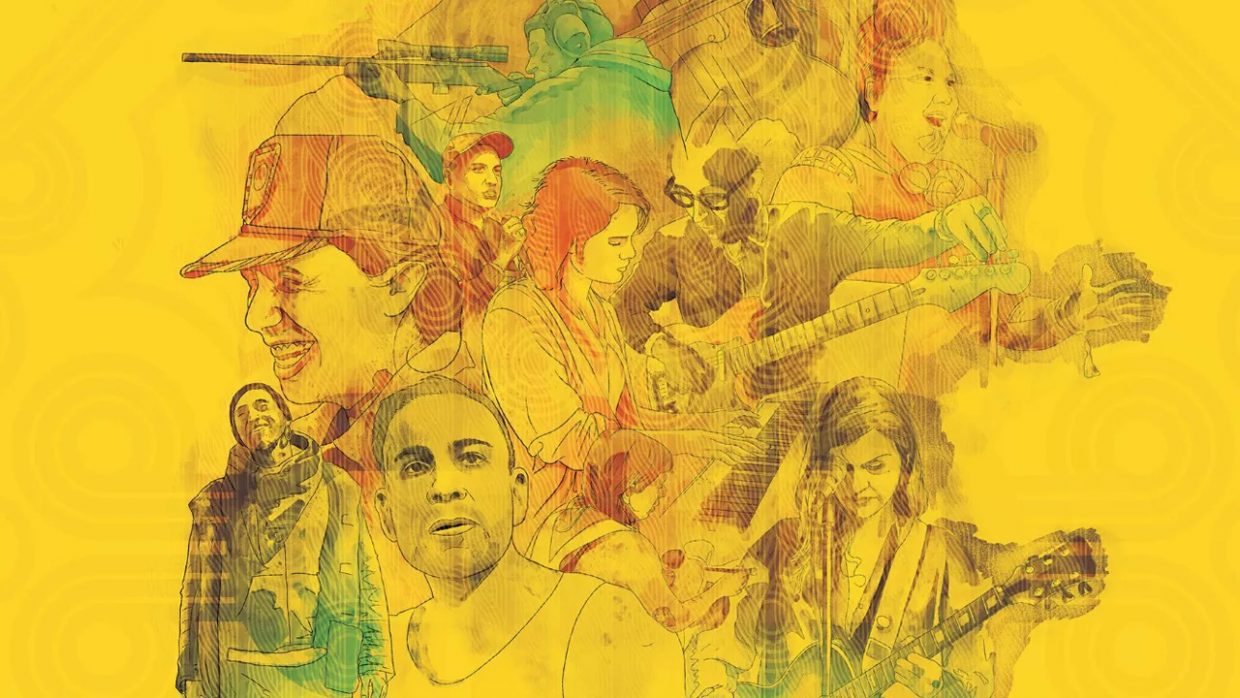

Love and Fury (Photo: ARRAY)

Love and Fury (Photo: ARRAY) Sterlin Harjo is a longtime Sundance alum who’s directed two docs, three dramatic features and a slew of shorts. He’s also a founding member of Native American comedy quintet The 1491s, and his first comedy series (for FX and streaming on Hulu), the terrifically titled Reservation Dogs, boasts a team exclusively made up of Indigenous writers, directors and series regulars (including EP Taika Waititi who co-wrote the first episode).

In other words, Harjo’s identity is solidly Native American (Muscogee Creek/Seminole) and solidly creative artist. Which may make Love and Fury the veteran director’s most personal film yet. (Not to mention his most far-reaching as Harjo, who shoots almost exclusively in his home state of Oklahoma, spent a year-plus, pre-pandemic, traveling across the country and overseas.) The film, which I caught at last year’s Hot Docs, and subsequently got picked up by Ava DuVernay’s ARRAY, follows a fascinating slew of insightful Indigenous creatives working in a variety of mediums: from musicians and composers, to visual artists, to poets and writers (including our current US Poet Laureate Joy Harjo).

We meet an installation artist whose bead-based project serves as an ode to missing and murdered Indigenous women. (He explains that it “weighs one ton,” but is even heavier to put up every time.) A dancer speaks of her choreography as being all about love, but that doesn’t mean her pieces are “nice.” Another artist notes that her nephew is both “conscious and unconscious” of his heritage: proud to wear his Native dress at ceremonies, yet also bent on being a “Navajo man” for Halloween. A poet reads that, “every american flag is a warning sign even the one my grandfather was given as a code talker.” Or as the bead artist bluntly puts it, the idea that Native Americans are even still here is mind-blowing. And it’s precisely what gives him hope.

To find out what gives Harjo hope – and more pessimistically, whether he views “inclusion” as the new whitewash – Filmmaker reached out to the busy director the week before the doc’s Netflix release on December 3 (just in time for National American Indian Heritage Month, naturally).

Filmmaker: All your projects feel personal, but this one especially so. How exactly did this film come about?

Harjo: I have a lot of friends that are Native artists and musicians. I had noticed that the same conversations were coming up over and over all around Indian country. Artists have a great way of expressing things, so what better way to express how you feel than a collage of like-minded artists and performers?

Filmmaker: Part of the power of Love and Fury really comes from its intersectionality — it’s equally an Indigenous film and an artists’ film, without one identity diluting the other. Was the focus on interconnectedness a conscious effort on your part? A result of something more organic?

Harjo: It was both. I started with four subjects. I wanted to make a documentary on Canuppa Luger, Micah P. Hinson, Penny Pitchlynn (LABRYS), and Haley Greenfeather. Penny’s tour didn’t happen, so Emily Johnson became more of a main character of the documentary.

Then I just let everything else unfold organically. I met Demian (Dinéyazhi’) through Canuppa and his wife Ginger. We filmed Demian and Canuppa getting their hair cut by the great Laura Ortman, so I ended up breaking off and filming with both Demian and Laura. That’s how the whole production went. The band Black Belt Eagle Scout are friends, and sometimes they stay at my place when they come through Oklahoma on tour. I turned the cameras on and then filmed their show. It felt very Indigenous to just let it expand organically like that.

Filmmaker: The title — which refers to the Native capacity to “convert fury into love,” as one of your characters puts it – also really captures the maddening contradictions inherent in the Indigenous experience. An Indian child who wants to dress up as a “Navajo man” for Halloween. Every American flag being a “warning sign” – even for those who’ve served in the US military. Are dark absurdities like this what fuel your own comedic endeavors? Is something like Reservation Dogs a conduit for turning your own fury into love?

Harjo: I’ve never thought of it like that, but I believe it is. I think Indigenous humor is always a close neighbor to fury and the tragedy of the past. It’s survival. It’s making sense of the senseless. There’s humor in that.

Filmmaker: The cross country aspect of the doc seems rather unusual for you, given that you’ve managed to build an entire career in film without ever much leaving home. So why was it important for you to physically travel for this project (especially considering that Oklahoma has so many tribes that I’m guessing you could have found many talented artists in state)?

Harjo: I was trying to express how this conversation was happening everywhere. It expanded past Oklahoma. It expanded past what white people think Native artists are. It expands past any box anyone tries to put us in. It was about shedding the restraints and showing us for what we are. The film is one big conversation. I could’ve cut it ten different ways and it would still be the same conversation.

Filmmaker: Though this is an Indigenous production, and all the writers, directors and series regulars you’re recently collaborated with on Reservation Dogs are likewise Indigenous, the execs at the top that ultimately call the shots at FX and Netflix are obviously not. So I’m quite curious to hear your thoughts on the film industry’s – and America’s for that matter – laser focus on expanding (and selling) diversity at the expense of equality. Is “inclusion” just another word for whitewash?

Harjo: I’m not sure what “inclusion” means. I know there was a time when I got treated a lot different in the industry. There were times when I was told that Native projects didn’t sell. That I needed a white lead to make any money. You always have to be a little suspicious when money’s involved.

In the end, all I can do is continue to make my work. There were a lot of years of being a filmmaker when I was struggling to keep the lights on, so I’m gonna enjoy this and not analyze it too much.