Back to selection

Back to selection

“Burnout and Fatigue and a Loss of Sanity”: Matthew Heineman on Making COVID-19 Documentary The First Wave

The First Wave

The First Wave Mass confusion and panic infected much of the world at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic as the deadly virus spread from country to country at an uncontainable rate. As many governments put temporary lockdown and quarantine orders in place (in addition to urging hospitals to boost patient capacity), New York City found itself the epicenter of the pandemic, ambulances constantly roaring as they raced to prevent the next round of deceased patients stored in meat trucks and disposed of in mass graves on Hart Island. With some distance from that horrific spring of 2020, new variants and vaccine hesitancy threaten to again overwhelm local hospitals and healthcare workers.

Set in Queens at Northwell Health’s Long Island Jewish (LIJ) Medical Center, Academy Award-nominated director Matthew Heineman (Cartel Land)’s latest documentary, The First Wave, places us alongside healthcare workers as they race against time to identify the symptoms and prevent the proliferation of the virus from taking hold of patients dying at an alarming rate. As ventilators are brought in to help bed-bound men and women grasp on to dear life, distressed family members FaceTime from home, praying for loved ones to recover. Less the cinematic embodiment of appreciative neighbors banging pots and pans every evening than a horror movie unfolding in real time, The First Wave, in its unprecedented access and unflinching details, showcases one of the darkest moments in recent history.

After a limited theatrical run in November, The First Wave made its streaming premiere on Hulu last week. I caught up with Heineman to discuss the rapid need to make this film, precautions taken and the ways in which the story changed throughout the course of production.

Filmmaker: Dr. Don Berwick—a participant in your earlier documentary, Escape Fire: The Fight to Rescue American Healthcare—connected you to Northwell Health and that’s how you received filming access to their largest hospital. But at what point did you even consider making a film about the pandemic? Had you been reaching out to different hospitals as we entered the early stages of COVID-19?

Heineman: I remember waking up like everyone did in early March of 2020 and feeling terrified by the sense of a tsunami coming towards us. We were inundated with countless stats and headlines and misinformation about the pandemic, and I felt a huge obligation to try to put a human face to it. I wanted to film inside these hospitals to show what was actually happening. At the time (and even now in retrospect), it was really sad to think that something that could’ve brought our country together ultimately divided us further, and a huge part of that was due to us not being allowed to see images from within the hospitals. People kept talking about the pandemic as this “war” we were fighting—but if you survey the wars throughout recent history, there were always journalists on the ground documenting what was taking place. Their journalism then, in turn, informed public opinion. With COVID, we were incredibly shielded from all of that, and that’s what allowed misinformation to spread to the degree that it did. Science and truth really were under attack and that was a big part of why we felt an obligation to tell this story. We set out to contact several hospitals across the country and ultimately received access to LIJ in Queens.

Filmmaker: Given the speed with which the pandemic was intensifying, were you even able to visit the hospital to map out how you wanted to film each ward? Were you perhaps given a floorplan to help with your pre-production phrase (assuming there was any time for pre-production)?

Heineman: Not really. With my documentaries, I generally don’t do a lot of research beforehand and, of course, the prep is much different than on a narrative film. We’re documenting real life as it unfolds, and so, the second we gained access, we began filming and finding the characters we wanted to follow and the subjects we wished to explore. As in my previous documentaries, I wanted to focus on a few individuals who would ultimately tell a larger story. If we can focus on the micro, then hopefully we can tell a story that encompasses the larger themes of how COVID impacted our society. With that in mind, we were looking to follow a few doctors and nurses, but also patients, as well.

Filmmaker: When you dive headfirst into filming, when do those characters become apparent? Do you just film as many relevant people as you can, then find the narrative threads in the edit?

Heineman: No, but I think a younger version of myself would’ve felt less secure and filmed many more people just to make sure. But, from the very beginning, we were deeply invested in the people we ultimately devoted the most [screentime] to, like Dr. Nathalie Dougé and Kellie Wunsch [registered nurse] and Brussels Jabon [nurse practitioner]. There are obviously a few other people that we filmed [that aren’t in the finished cut], but for the most part, who you see in the film is who we invested in the most. They are our storytellers.

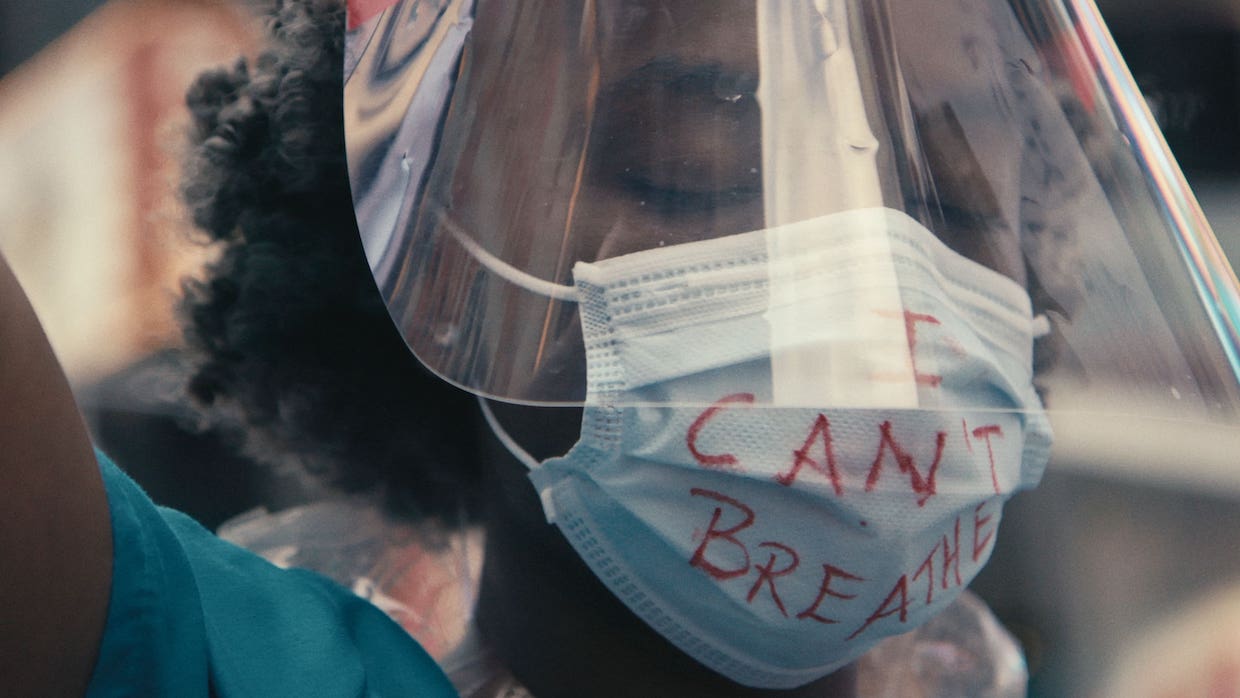

Obviously, there are other “characters” in the film, New York chief among them. Shots of empty streets when the pandemic began [are contrasted with] the filling of streets for the protests that followed the killing of George Floyd. Then there were a chorus of characters that you see within the hospital but don’t really get to know personally like you do our main subjects. It was important that you get a sense of the energy that was coming from within the hospital at all times. And, as it pertained to the world outside of the hospital, we wanted to include affected family members of the patients.

Filmmaker: I wanted to ask about those situations where family members weren’t allowed to visit LIJ to see their loved ones while they suffered from COVID. Early in the film, Dr. Dougés makes the heartbreaking phone call to inform a family member that their loved one could not be revived. You have us hear both sides of that intimate conversation in real time, and I imagine that’s something you have to get pre-approval of to record. How were you able to respectfully work out those logistics with the hospital?

Heineman: The whole process was very complicated on every single level: logistically, physically and emotionally, and yes, navigating the receiving of consent from patients to record was very difficult. However, we always did receive their consent and followed a number of different stories as a result.

Filmmaker: Maneuvering around the emergency room and other small quarters of the hospital must not have been easy. As the director, you want to be as close to the action as possible while remembering that this is a very real operation where lives are literally on the line. What kinds of conversations do you have with your cinematographers regarding camera/cameraman placement?

Heineman: We had a very small team working on this film and there were even times when someone would have to go out and film all by themselves or have to operate filming two stories simultaneously. I really wanted my team to be huddled together and right in the thick of the action, but at the same time, the goal had to be to leave the tiniest of footprints. What that means is, we’d often have people filming by themselves in a hospital room, or occasionally with a field producer or with myself depending on what the situation was. As the director, the look and feel of these scenes were important to me and a sense of immediacy needed to remain at the forefront. However, while there’s a lot of action taking place inside the hospital, it still remained a very stale environment, lighting-wise, and we were often at the mercy of being boxed into very small spaces. It was difficult to navigate, but across our various DPs, we used alternate cameras with different sized lenses to create that sense of place. Hopefully our combined work in the film feels relatively seamless.

Filmmaker: As you coordinated who was going to be at the hospital when, were there certain precautions you each had to take as you arrived or departed the hospital each day? I think we had COVID tests available by this point, maybe even rapid testing available, but it’s a bit of a blur. Were there isolation/quarantine protocols you had to logistically match up with your shooting schedule?

Heineman: There was burnout and fatigue and a loss of sanity. These were all real things, and that’s why we generally didn’t want people to shoot for more than several days a week. The hospital obviously had a rotating “cast” of people coming into the hospital and that made the logistics incredibly difficult. Every aspect of making this film, especially the things we sometimes take for granted as filmmakers, were all potential weapons for transmitting the disease.

Filmmaker: What are some examples of those difficulties?

Heineman: Putting lav mics on each person, placing the camera down on a hospital countertop, the way we removed our clothes at the end of each day—these were all things that could potentially spread the virus, or so we thought. At that point in time, with the limited knowledge we had about COVID, we had to develop our own safety protocols. Any of our crew members who had families they lived with were given temporary apartments and rental cars to isolate away from their families. The whole thing was a logistical puzzle.

There was so much fear and sadness and deeply troubling moments throughout the shoot, but the overall feeling we kept was to appreciate the incredible fortitude and courage and love we witnessed every single day between the staff and the patients we were documenting. That feeling of inspiration pushed us day in and day out.

Filmmaker: One of the patients you document and dive into the backstory is Ahmed Ellis, a NYPD school safety officer who, when the film begins, is a patient at LIJ battling COVID-19 for what amounts to over two months. Given the severity of his illness, you couldn’t possibly have been aware of what the future of his health would look like, and I wanted to ask if that ever affects who you choose to follow as a subject. Of course, we hope that his health will take a turn for the better, but it’s obviously in doubt and could partially rob your film of the uplift it concludes with—

Heineman: Hmm, just to clarify, are you asking if it’s difficult for me, as the director, if a subject we’re following could either live or die over the course of filming?

Filmmaker: Essentially, yes.

Heineman: Well, it was very difficult in that we were constantly documenting the razor thin edge between life and death. That’s what makes the virus so insidious, right? Someone who was healthy and showed no signs of pre-existing conditions could suddenly pass away. Then there were people who had the virus and had everything set against them, yet they somehow survived. People who were getting better could suddenly take a turn for the worse and vice versa.

To answer an earlier question, getting tested for COVID-19 was extremely difficult at this point in time (there certainly weren’t any rapid tests available then). It was difficult filming patients on the edge of life and death and that’s what made it so difficult for doctors and nurses. You train your whole life to understand the human body, only to see all the years you’ve studied and all that you’ve learned suddenly get thrown out the window. The profound mental health implications of that are still felt, even a year-and-a-half later.

Filmmaker: The film is titled The First Wave and takes us through June of 2020 and everything that was happening in America via the country’s Black Lives Matter protests and racial reckoning. But as you were making the film, what was the key moment on which to end? We anticipated an incoming coronavirus “second wave” when the weather would start to cool down and people would be back indoors, but at what point did it become apparent to you that the first wave was going to exclusively be the story you were telling? Did you ever consider continuing to film into the fall and winter of 2020?

Heineman: We actually did continue to film throughout summer and into the fall, not exactly knowing what the goalposts were going to be, editorially at least. It wasn’t until we got into the edit and came up with that title, The First Wave, that we realized the “big story” implications a title like that possesses. It’s rare that a film’s title, in my career, has had such editorial importance, but as we kept trying to edit the film to see how we could continue the story into the fall of 2020, it just never fit the narrative. When we arrived at the title of The First Wave, establishing the goalposts as being from March through June, it gave us the timeframe with which to centralize the story and help us clearly see the story arcs of our main characters. That decision was a big part of establishing where the story began and finally concluded.

Filmmaker: As you were filming, and then editing, The First Wave, you were also doing press for other features you had recently directed. There was Tiger, the documentary two-part series for HBO, and The Boy from Medellin for Amazon. What’s that experience like, where you’re working fervently on one project at night while promoting another film already in the can during the day?

Heineman: It has been a crazy couple years, for sure. But even now, as I’m at work on a number of different projects, there’s no question The First Wave is the film I’m most proud of. It’s the film that I’ve been most focused on and have poured every ounce of my soul into making, alongside an incredible team of filmmakers. We all felt this huge responsibility to the story and were very aware that we were given access that other people didn’t have. We knew that this was a once in a lifetime event and didn’t want to screw it up. I’ve never worked harder on a film, nor have I ever cared as much about one. I hope it can stand that test of time.

Filmmaker: In the press notes for the film, you referenced a quote you once heard from Albert Maysles, that “if you end up with the story you started with, you weren’t listening along the way.” In what ways could that quote apply to The First Wave?

Heineman: When I was 21 years old, I heard the Maysles quote that you mentioned and I think it’s good advice for filmmaking and also life, in general. It’s something I’ve held near and dear to my heart every step of the way, in my career (in a macro sense) and in each film (in a micro sense). If you’re open to the story changing, you won’t risk being dogmatic.

A film that started out as an homage to healthcare workers became so much more—about the trauma, isolation, love, family, birth and death that we cover along the way. It also became about the disproportionate impact this disease had on people of color, as we show via principal participants in the film. We also show the nation’s reckoning with systemic racism via Dr. Dougés, a first generation American from Haiti who protests in the streets following the killing of George Floyd. If you had told me when I started the film in March of 2020 that we’d be filming protests in the streets of New York in May or June, I would’ve said, “Well, that doesn’t make any sense. That’s not the film we’re making.” But of course, that has exactly been the film we were making, and that’s the film we made. That’s what I love about making films, to be open to following where the story leads you.