Back to selection

Back to selection

“I Never Saw This as a ‘True Crime’ Series”: Nanfu Wang on HBO Docuseries Mind Over Murder

Mind Over Murder

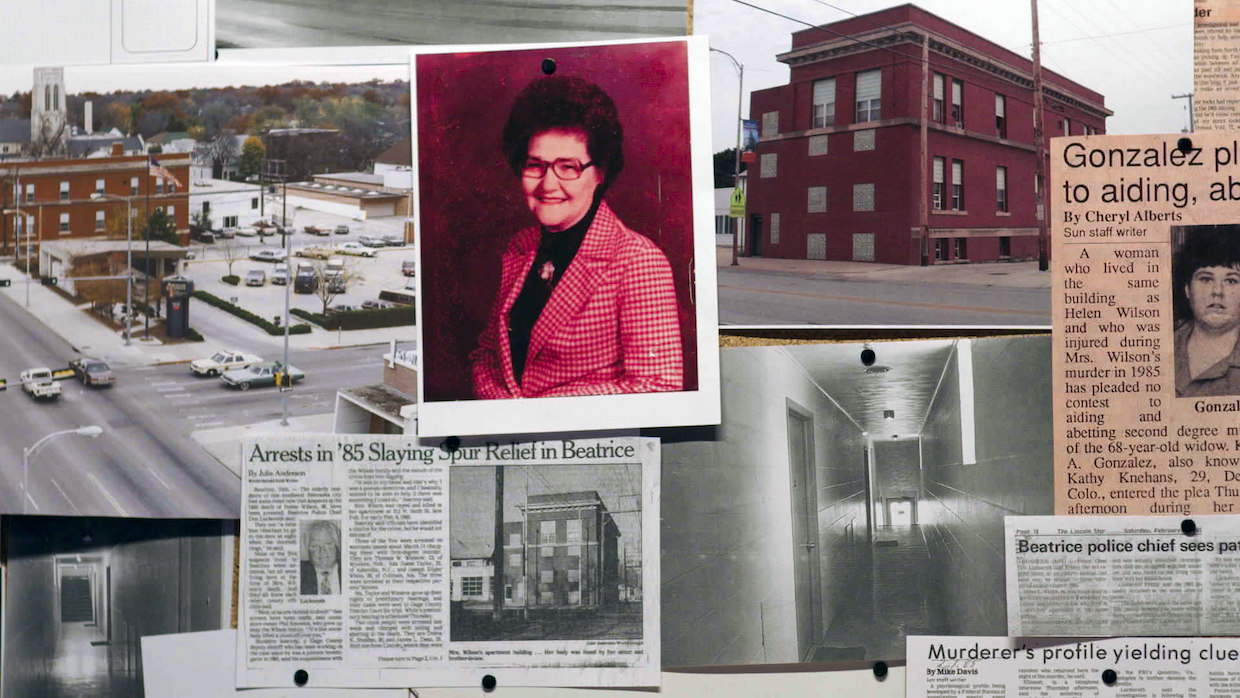

Mind Over Murder One of the more surprising revelations in the provocatively titled six-part docuseries Mind Over Murder has nothing to do with the sad tale presented onscreen of the “Beatrice Six,” as the three men and three women convicted (and ultimately absolved) of killing a beloved grandma in Beatrice, Nebraska back in 1985 came to be known. Instead, the surprise comes when the end credits disclose the story is being revisited by none other than critically-acclaimed director Nanfu Wang (In the Same Breath, One Child Nation), not exactly a usual suspect for the sensationalist true crime genre.

Then again, Wang doesn’t seem much interested in adhering to any tabloidesque playbook, tossing cinematic tropes of both heroes and villains straight off the screen, a choice that ingeniously swings Mind Over Murder in a far more consequential—and ultimately existential—direction. Unlike the current crop of sleuthing journos bent on becoming the next Errol Morris, Wang is not looking to prove or disprove anything. The case has already been exhaustively laid out in numerous, decades-spanning trials and investigations (from which she deftly deploys footage), resulting in a 2009 DNA acquittal for every single member of the Beatrice Six. Rather, Wang’s come to the small-town scene of the crime to conduct contemporary, on-the-ground interviews, patiently probe the minds of all the living players and document the amateur players in a local theater production as they develop, wholly from courtroom transcripts, what they hope will be a source of truth and reconciliation.

The real mystery that Wang has set out to solve is how both a community and a victim’s family can be split on the question of a person’s innocence even in the face of solid exonerating evidence—and whether it’s ever possible to dislodge a false narrative once it’s become insidiously ingrained in an individual’s identity. Denial, after all, is a form of self-preservation, whether you’re a grieving relative desperate for closure, an (in-over-your-head) investigator desperate to provide it for that loved one or a wrongly accused individual prone to manipulation by a desperately self-preserving authority figure.

To try to get at some answers, Filmmaker turned to the empathetic, China-born-and-raised documentarian herself (who happens to know a thing or two about believing in false narratives propagated by self-preserving authority figures). Episodes of Mind Over Murder began dropping on HBO June 20.

Filmmaker: I was pretty surprised to see your name attached to a true crime docuseries. Did Vox Media Studios, which produced the miniseries, pitch the project to you? What drew you to this complicated material?

Wang: I never saw this as a “true crime” story myself and don’t usually watch true crime shows. To me, it has always been a story about the fallibility and malleability of memory. And, speaking of memory, I still vividly remember when and where I encountered this story: June 17th, 2017, while on a plane to Michigan to surprise my mother-in-law for her 60th birthday. I read an article in The New Yorker titled “Remembering a Murder You Didn’t Commit.” I was transfixed. I knew after reading it that I wanted to explore the story as a filmmaker.

My understanding of memory was completely transformed after I made my first documentary, Hooligan Sparrow. I shot that film in 2013, and in 2015 after I’d finished editing I showed the film to the protagonist Ye Haiyan (aka “Hooligan Sparrow”). After watching it we talked together about the story and reminisced about our shared experience of making the film. As we were talking, something happened that shocked me. Ye Haiyan recalled that the film’s timeline was exactly as she remembered it happening in real life—but I knew this wasn’t possible. I’d made some minor changes to the chronology of events in order to make the story clearer. In that moment, I realized that seeing the film had reshaped her memory. My presentation of her reality became her reality. This was my first encounter with the idea that memory is plastic and shapeable. Of course, I knew how fragmented my own memory could be, but I never expected that I could retell someone else’s story to them, then watch them internalize and transform it into a memory that they considered their own.

So, when I read the story of the Beatrice Six in The New Yorker article, and learned that several of the six “remembered” committing a murder that they had nothing to do with, I was immediately intrigued. It put the idea of memory’s plasticity into an urgent context: justice. The story stayed on my mind for a long time. One day I mentioned that I wanted to make a film of it to a person who happened to be friends with Max Heckman, a development executive at Vox Media Studios. She told me that Max had also been fascinated by the same story and had actually traveled to Beatrice to meet some of the people involved. So, Max and I got connected through our mutual friend. Immediately it became clear to us that we shared the same passion and vision for the story. We decided to work together, and I traveled to Beatrice for the first time in May 2019.

Filmmaker: I’m guessing that your status as a “neutral” outsider might have played a role in getting folks to open up to you. How did you gain the trust of so many characters on polar opposite sides of the story?

Wang: The simple answer is time and authenticity. As a Chinese woman visiting Beatrice, Nebraska, a place where the majority of people are white, during my first trip I quickly realized that I stood out. I attracted curiosity and suspicion wherever I went in town. People wanted to know who I was, why I was there and why I was interested in telling their story. Many of the people involved in this story distrust the media, so it took time to build trust with them. I’d communicate with them via email and phone calls and through several in-person meetings without a camera. They could ask me any questions, get to know me, my motivation and my intentions. I tried to explain that I wanted them to share their experience from their perspective, why their perspective was crucial to understanding the full story and that my ultimate goal was to help show the truth and bring clarity and reconciliation to people.

Being in a small community sometimes helps. When one person decided to trust me, they’d introduce me to their friends and family. I could gain access to people and places more quickly because of that personal connection. But because the town is so divided—and people have such polarized opinions towards the Beatrice Six and law enforcement—being in a close-knit community also means that if I hung out and talked to one group of people, the people on the other side would soon find out too, which made it even more important to be honest and transparent about who I talked to and what I had been doing.

Throughout the making of the show I ended up spending more than 100 days in Beatrice. During the rehearsals for the play, I actually moved my family to Beatrice for six weeks and my son attended a day care in Beatrice. I felt very connected to the community. That experience of being immersed in life there helped tremendously in getting people to open up and trust me.

Filmmaker: One thing that truly sets this series apart from the genre is your refusal to create heroes and villains. Even Burt Searcey, the former cop-turned-investigator responsible for “railroading” the Beatrice Six, is presented as yet another flawed human being in the story who got in over his head. Were you consciously aware of upending the “good versus evil” trope—or did that just happen organically?

Wang: It was very important to me throughout the making of the show to not reduce the story to a simple “good versus evil” or “hero versus villain” story. I think it might be easier to tell stories with heroes and villains, but real life is often much, much more complex than that. Human nature can’t be reduced to something that can be put into boxes labeled “good” or “evil.” Even the most “evil” person can be perceived as kind and caring in their loved ones’s eyes, and the “nicest” person also has flaws. Humans are complex. That’s why the story of Helen Wilson’s murder and the Beatrice Six’s wrongful conviction is a tragedy on all fronts, for all the people involved. My goal has always been to help the already divided community find mutual understanding, closure, healing and reconciliation. And to accept the truth. I think if the story was told in a simple, black-and-white way, it would’ve only further divided them.

Filmmaker: Watching the series, I was reminded of hearing you speak (at Hot Docs pre-pandemic) about first learning of the Tianamen Square massacre once you got to America. It struck me that you seem uniquely positioned, having grown up in a country of false narratives, to empathize with folks so invested in a story that they are unwilling to even entertain the idea that their “truth” is possibly a fiction. Did you actually discuss your own experience of being “brainwashed” by authority figures with those you were filming?

Wang: I didn’t talk specifically about Tiananmen Square with them, but they knew my backstory—that I grew up in China and came to the US in my late 20s. Some of them told me that they had researched me, and some had watched my previous film(s), either out of curiosity or when they were weighing whether to trust me to tell their story. From what they told me I think they appreciated the empathy I tried to approach my subjects with, and I think they believed that in my work as a filmmaker I genuinely was searching for the truth. It definitely helped them to open up and trust me.

Filmmaker: How have the characters and community been preparing for the HBO release? Is there a feeling of apprehension or excitement? A mix of both?

Wang: Most of them had a mix of both excitement and anxiety before they had watched it. We managed to show the main participants—including the Wilson family, the civil attorneys representing the Beatrice Six, Burt Searcey, Lois White (wrongfully accused member Joe White’s mom) and more—all six episodes ahead of the premiere. Otherwise it’d be an anxious and long wait for them to see just one episode every week. So, they watched them, and each of them said they liked the show. Many of them are even planning to watch it a second time on HBO and HBO Max. During the making of the series I said to each of the participants that I wanted to tell a story that would truthfully represent their experience, and that I hoped that regardless of which side they were on and what they believed, they’d find the story meaningful and truthful. And they did. Getting that feedback from participants on both sides, hearing them express their approval and appreciation for the storytelling after they’d watched the show, has been the best and most rewarding experience.