Back to selection

Back to selection

Texts and Contexts: On Rethinking the Teaching of Cinema Studies in 2022

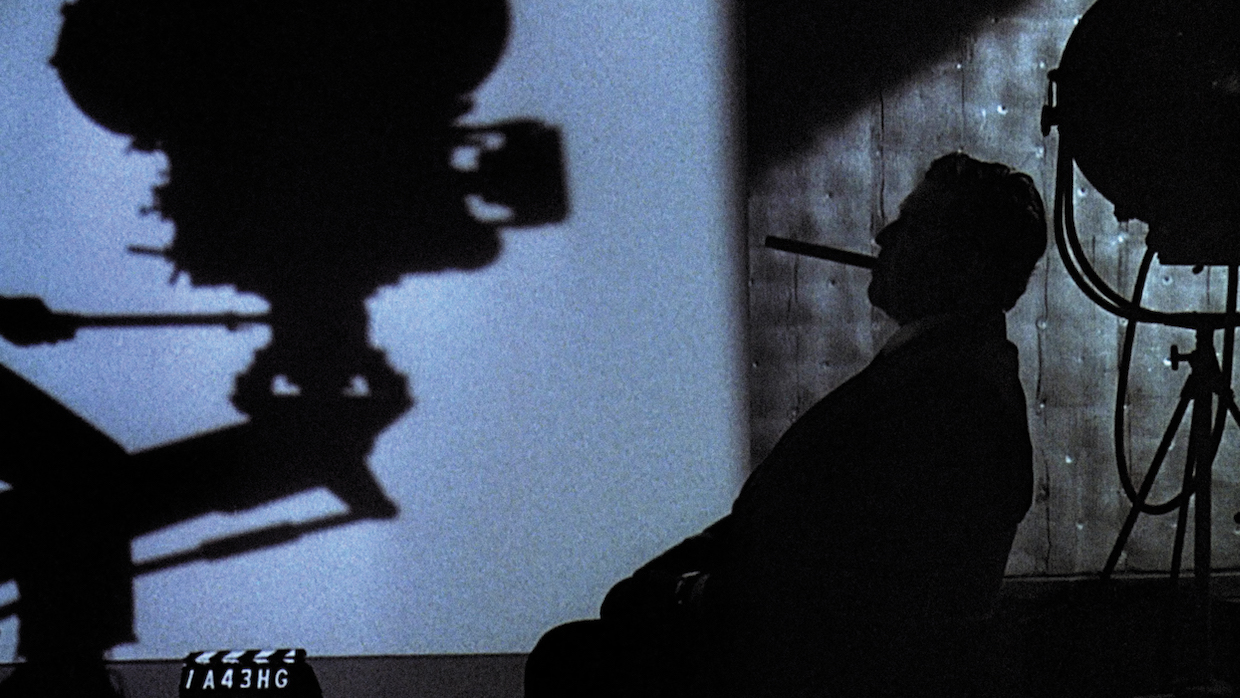

Matinee (courtesy of Shout! Factory)

Matinee (courtesy of Shout! Factory) My students know how to edit footage and use a zoom lens; they’re experts on lighting and composing a shot. But because they learned those techniques through their phones to upload to social media platforms, they use them in a completely different manner than what usually gets taught in a filmmaking class. It might be easy to dismiss these skills, developed mostly to impress their friends, but more and more jobs are looking for university graduates who can create, use and distribute video content (or just light themselves for Zoom). In that model, appreciating a movie is not exactly a requirement.

How does one approach understanding filmmaking when the traditional narrative feature is hardly the dominant form of media? Smartphone filmmaking has given introductory cinema classes like my own, “The Art of Film,” a unique challenge. I began teaching my class—essentially Film 101—in 2021 at San José State University, a state school where many students work part- or full-time and often come from first-generation backgrounds. Living in the shadow of Silicon Valley, many students focus on STEM and business majors but end up in my class when looking to fill a general education requirement with something a little more fun than Shakespeare.

However, the idea of the 90-to- 120-minute feature is in some ways closer to Shakespeare, a historical form of art. I noticed this when students watched our first film of the semester, Joe Dante’s Matinee. Its very traditional narrative construction is right out of the classical Hollywood playbook and would hardly surprise most viewers of a certain age. Yet, a number of students considered the numerous subplots and characters to be as complicated as those of any Christopher Nolan film.

Given these changing dynamics, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how to keep the core of these kinds of intro classes by merging the basics of film aesthetics with new approaches that might correspond more closely to issues students faced in their educational and working lives. I was not about to leave mise-en-scène or deep focus by the wayside but wanted to think of additional tracks that matched the conditions and anxieties expressed by workers, critics and artists in the industry today. I am hardly the first person to try to rethink the introduction to film class. My fellow members of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies, particularly in their Teaching Media dossiers, have written wonderfully about innovations they have developed in the classroom. But some of my whims took me in different directions that could not only help young filmmakers but could also alter the mindset of an expanding market landscape of media workers.

Introduction to Film usually features standard components no matter where it is taught. Instructors often begin with a discussion of aesthetics you will likely recognize from your old Bordwell/Thompson Film Art textbook: narrative, mise-en-scène, cinematography, editing, sound. The general idea is to teach film language so students can grasp how films make meaning, whether by examining why the camera puts some details in the frame in focus over others or more complex ideas around how a film develops a message separate from the main character. My own lectures use scenes from recent works like Moonlight, Parasite, The Book of Eli and Marie Antoinette, with a few historical examples thrown in (I cannot resist showing that opening long take from Touch of Evil). Given that these are often terminology heavy, I frame lectures as learning a new language students see all the time but have never had to articulate before.

But these terms are partially what students find confusing: “Editing” for them isn’t arranging shots but actually doing color correction, while eyeline matches hardly seem critical for designing a scene. Ironically, in my experimental film seminar—where we ignored film terminology all together— students found it easier to engage with the images when not having to consider how traditional films are put together. In the age of the smartphone, that Touch of Evil long take has lost its appeal; what students desired were ways to think about film beyond the text itself.

Covering the basic principles of moviemaking rarely takes a semester, so professors usually follow a few different paths from there—looking over colleagues’ syllabi, I found most included a mix of genre studies, film theory, alternative forms like animation and documentary or issues in representation or globalization. Having sat through these lectures as a teaching assistant, I know they can be effective. However, I also found they could require intensive historical frameworks that felt anachronistic in today’s media landscape. Genre studies emphasizes the differences between horror and noir, but students more commonly now examine the differences between YouTube tutorials and longform television. Another example: documentary studies often emphasizes the differences between filmmaker and subject, but most nonfiction that students watch has entirely blurred that line without the political connotations once associated with doing so.

In my first attempt at the class, I decided to emphasize the route I had taken as an undergraduate with film theory, thinking about the nature of cinema and its role in society. Students read André Bazin, Sergei Eisenstein, Laura Mulvey, Stuart Hall and bell hooks, among others. My hope was to give students an introduction to college-level reading through “difficult texts” while also engaging with the properties that make the moving image unique. I was not entirely surprised that my students found the language in these articles challenging, but they actually had much more trouble grasping the ideas when I laid them out in my lecture. Questions about realism, the apparatus and the spectator felt entirely out of place with the present moment. Eisenstein’s theories about montage and creating political ideas felt old hat given the amount of election ads they see every year. And how did the apparatus control and influence spectators if they were just watching a phone on the subway? There was some value in these essential texts, but I had to spend more time explaining the politics of mid-century Europe than how they related to today.

I realized that while I enjoyed film theory, these were not the questions I had in my research, either. The best scholars I know today are using different strategies and tools that were not around when these foundational texts were written. They are rethinking how audiences react and relate to film, analyzing labor dynamics, calculating environmental damage caused by DCPs and finding the hidden contributions of BIPOC workers in every nook and cranny of history. If this class was to introduce students to why they might study film, I realized I should teach it in a way that better reflected what scholars today think is important in the field. I kept the films the same—canonical works like His Girl Friday and The Watermelon Woman along with newer indies like The Fits and Mary Jane’s Not a Virgin Anymore—but reoriented my lectures toward why film studies still mattered.

In my third go-round, I broke the semester into two parts: text and context. We would try first to understand “what is a film,” then open up to see how films interacted in society. I tried to lean into what made me most excited about thinking about film and, in turn, what might excite students. My second half of the class thus took up five core topics: industry, representation, audiences, technology and labor. Rather than focus on canonical articles, I turned my focus toward contemporary research and issues that students knew and experienced: how is Netflix changing how movies were made? Why do all Marvel films look the same? How is it possible there is simultaneously more and less diversity in the industry? I wanted to make the course feel specific and give students the tools to see how filmmaking works today by moving beyond what the industry made to who made and received it.

I thought students would enjoy the less textbook-heavy material but was still surprised how much more it mattered. Their discussion posts became lively with personal experience and argumentation that was missing in the more straightforward first half. Students were still somewhat lost with Laura Mulvey but latched onto Kristen Warner’s ideas of analyzing casting decisions and forcing actors into what she calls “plastic representation.” My week on audiences focused on how different screening experiences could transform the meaning of a film; students fondly recalled the differences between watching films on their laptops compared to roaring crowds for films like Spider-Man. During my week on technology, I explained the differences between celluloid and digital projection by centering how it transformed the labor specialization of projectionists. Most notably, students found surprising resonances while reading Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s famed essay on mass culture, connecting it not just to the Marvel Cinematic Universe but also their TikTok and Instagram feeds.

More importantly, I centered workers rather than artists. Given the pitfalls and misunderstandings that come with auteurism, I tried to situate filmmaking as a creative endeavor negotiated by dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals, both before and after they step onto a film set. Rather than a perfunctory acknowledgment of labor, I wanted them to examine how collaboration and control at any level—from corporate shareholders to gaffers—could ultimately change the meaning of a film in the ways we analyzed in the first half of the class. It’s one thing to teach why a creator might choose a Steadicam rig over a dolly shot for creative purposes, but I wanted students to understand that it often was a question of budget or scheduling. When it came to censorship, we looked at documents from the Department of Defense regarding Ang Lee’s Hulk and compared them to reports on China’s import program and demands made of studio films. Only after a semester discussing how choices came down to creativity and studio control did a clip from Business Insider promoting TechViz—where studio animators can essentially decide every shot far in advance of working on a set, leaving very little for the director to decide—cause my students to see how and why I emphasized industry and labor and why it matters who makes these decisions.

By orienting the class toward the work of cinema rather than the art, I hoped for them to engage with cultural objects in a way that could eliminate bad habits. If it is easy to be annoyed by criticism that combines analysis and theory with questionable poor-faith tactics for clickbait, I wanted my students to engage with the issues that are at the center of the industry today, like safety, financialization and accessibility. Rather than focus on the realism of a shot, I focused on the reality of Georgia’s tax breaks. I ended the class by discussing the unions that dominate Hollywood and noted how, decades before gig workers became a central part of our economy, these unions negotiated issues for freelance workers jumping from studio to studio. These were the kind of things I never learned as an undergraduate that could have entirely transformed how I thought about film. In our last class, I had students look up behind-the-scenes materials on their favorite movies to understand what processes affected their production and learn the names of those workers who made them happen.

For our final screening, I showed Kirsten Johnson’s Cameraperson. I explained to my students that in a day and age where we see so much of the world through our screens, here was a film that not only valued the idea of a cinema worker, but also asked us to think about how the world changes when we see it through a camera. For my students, understanding who was holding a camera, and why, was just as important as what the camera shows.