Back to selection

Back to selection

Magic, Misdirection and the Amazing Kreskin: Michael Bilandic and Owen Kline on Funny Pages

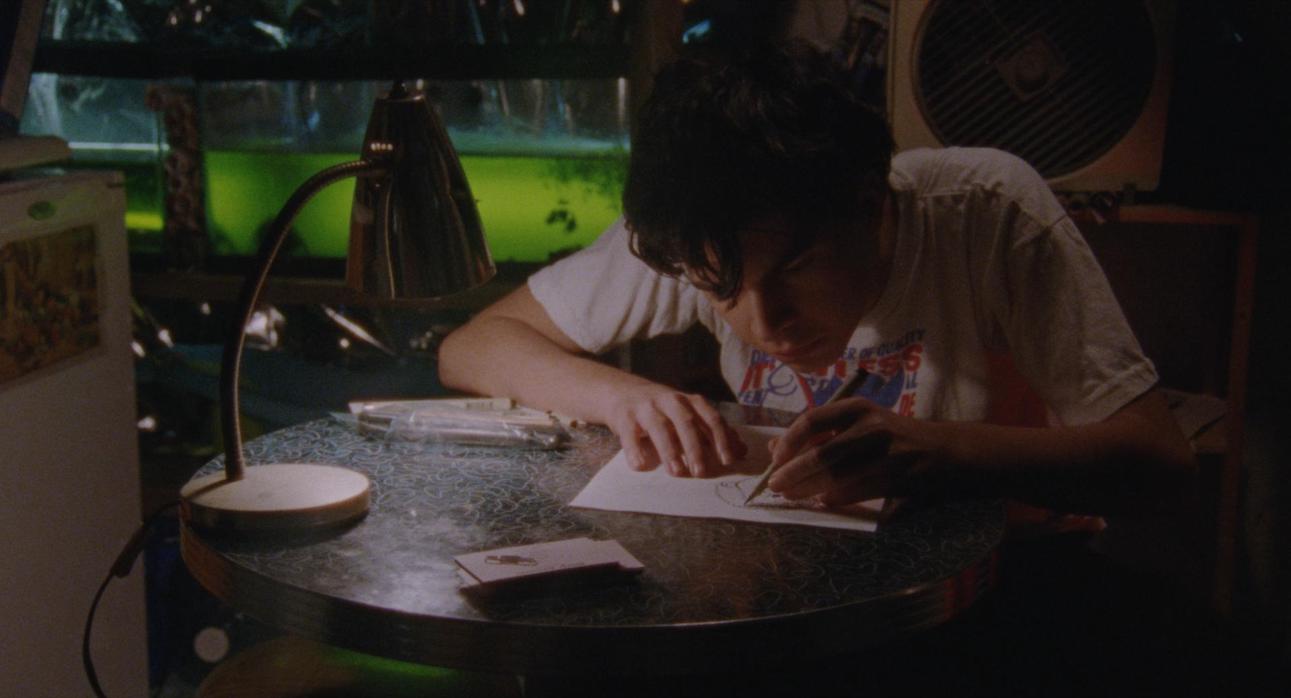

Daniel Zolghadri in Funny Pages

Daniel Zolghadri in Funny Pages Director Owen Kline texted me recently to let me know he was in my neighborhood, so we linked up in Washington Square Park to see what was good. He’d just gotten back from Cannes where his debut feature, Funny Pages, was a smash hit. I was excited to hear some glamorous, and hopefully debaucherous, tales from the Croisette. Instead, the very first words out of his mouth were, “Pick a number between between one and a thousand. And don’t tell me what it is!” He looked me dead in the eyes, on some mentalist shit, scribbled furiously on a clipboard for a bit, abruptly stopped and asked what the number was. Right as I blurted it out he flipped the clipboard around to dramatically reveal the correct number along with a goofy caricature of me. I was shocked, amused and impressed. These are common feelings elicited by the man and his work, and Funny Pages serves then all up in abundance.

While many people know Kline from his role as the youngest sibling in The Squid and the Whale, he’s been toiling away in the underbelly of NYC’s indie film and repertory scenes for over a decade now; interning at Anthology Film Archives while still in high school, making short films about cockfighting and Joe Franklin, crewing for and acting in various early Safdie Brothers projects, DJ’ing around the city and making comics. I’m still not sure how he attended my 2011 Happy Life premiere as a teen, but we’ve been friends ever since—he even graciously played bit roles in my own films Hellaware and Jobe’z World. Watching the evolution of Funny Pages from an idea for a microbudget, potentially mumblecore-esque exercise to a bigtime arthouse release, produced by Elara Pictures and A24, has been one of the great sagas of recent memory. On the eve of its release, Kline has also programmed two film series, full of rarities, oddities and lesser known masterpieces: Animating Funny Pages at Lincoln Center and Monomania at The Roxy in Tribeca.

Out this Friday from A24, Funny Pages is a brutally hilarious coming of age story about Robert (Daniel Zolghadri), a young cartoonist who becomes obsessed with Wallace (Matthew Maher), an obscure, out of work and volatile “assistant colorist.” Framed around the world of a suburban New Jersey comic book shop and its die hard denizens, it also features one of the most ludicrous boiler room flophouses of all time. I trekked over to Kline’s equally eccentric apartment to discuss magic, Burger King, the Astor Place Cube, Frownland bonus features and much more.

Mike: I haven’t interviewed anyone for a publication since 2005, when I profiled the bodybuilder-turned-heavy-metal-singer Thor for the Village Voice. Didn’t think I could ever chat with anyone bigger than that, so I quit the game. Yet here we are.

Owen: Just Thor and me. Just us Gods.

Mike: So, we’re deep in Queens at your home office. Every square inch is stacked with comic books, DVDs, 45s, Felix the Cat memorabilia, Baby Huey glassware and god knows what else. I feel like we’re literally in your movie. There’s a poster over your desk of a guy in a turban and it says “Chandu The Magician” which reminds me: you saw the Amazing Kreskin recently, right? How was that?

Owen: Pretty spectacular. I did the schlep to Atlantic City with Tony Hassini, my childhood magician hero, and Robin Channing—his right-hand mindbender—to see him. We show up and all that’s there is a giant big top, but no one seems to be going in and we’re just waiting for it to open. Turns out, he’s not performing in the big top. The show’s been moved to The Kiss Kiss Room at the Tropicana, a smaller venue. That’s a comedy club, strip club, bottle service place in an Atlantic City mall, and in the middle of it all there’s Kreskin in his coke-bottle glasses—mister zillion-plus performances on Johnny Carson, Letterman, Carson’s inspiration for Carnac the Magnificent and all that. The finale is a funny-seeming audience member, who has never met Kreskin in his life, gets to hide his check for the show in the venue while he isn’t looking, and you get to watch Kreskin find it. Kreskin drags the guy by the arm all around the venue like a dog. I think it used to be genuine muscle reading, but it’s not anymore. It’s like a lie detector test—he’s psychologically able to tell where it is based on the muscle tension in the audience member’s arm. Very weird skill to master, but it was just amazing. I go out there with these magicians, mainly because it’s billed as his last show before he is retiring. But man, at the end of the show he goes, “As I like to say, to be continued!” What a trickster.

Mike: Who’s the guy you went with, Tony Hassini?

Owen: When I was a kid, seven or eight, I became really interested in magic and got this video set by him from my late grandfather. He has a thick accent, he’s from Cyprus: ”Hello. My name is Tony Hassini and this is balloon magic.” He’s the guy who plays the pharmacist that Robert throws the ball at in the movie. He directed over 200 Burger King commercials featuring the “Marvelous Magical Burger King.” They had all these practical effects: the burger blows up with smoke, then the king appears. He figured out all those tricks, in-camera. I think about that stuff all the time.

Mike: That’s incredible, being the in-house Burger King magician and scheming up a thousand ways to blow up a Whopper.

Owen: Yeah, and he helped with the last crash in the movie and was around on set, working on illusions. Not kidding! Figuring out practical things requires the assistance of a magician sometimes. Ricky Jay used his services towards filmmaking, too—he was for hire in that way and would create illusions for the camera. Anyway, Tony is a wild character. I thought, for some reason, he seemed like the right guy for Robert to K.O. in the pharmacy. I don’t think he blew up a Whopper, but we should try that.

Mike: Your own magic’s leveled up since paling around with these elite icons. That “pick a number between one and a thousand trick” was too sick.

Owen: I thought it would be funny to just focus on that again in my life. It started as research for something and just became me torturing everyone with tricks, like I’m fucking eight again. I was never a good magician as a kid, but I was a good showman. I was very performative, so I liked these stage magic tricks. I’d see someone do a trick with two wooden rabbits or something, and I loved it. One’s red, one’s blue or whatever and they reverse. Really easy switcheroo stage tricks like that, I still can’t get enough of it. Stage magic as opposed to close-up magic, which is coin tricks and cards and stuff. The simplest principle you learn, once you start studying a couple tricks, is misdirection. It’s the principle of magic, basically. You’re showing something over here and tricking them into thinking that’s where the answer could be when, in reality, it’s way over there. That’s a helpful device to understand the principles of and can be directly applied to narrative storytelling. There’s a reason why they call magic the second oldest profession in the world, because all these techniques have been written about and recycled for hundreds of years. The “French drop” and all these things date back a zillion lightyears ago. But they just call that misdirection. It’s kind of the same thing when you cut away in a film. Usually you’re patching or hiding some shit that doesn’t work. You’re cutting something out that you can’t cut out any other way than by cutting to the baby or the dog in the corner going “Hm?” and perking up its ear. Because one of your actors is stinking up the joint and you have no other way of cutting the scene down.

Mike: Editing is almost entirely misdirection.

Owen: It’s all misdirection. I’m not super good at card tricks, but I know a couple of devices. If you’re crafty enough and you can palm a card in your hand and hide that from someone while you’re shuffling a deck, you’re halfway there.

Mike: It’s powerful stuff and can be used nefariously in the wrong hands. Pick-up artistry is the same thing. It’s no surprise these Hollywood freaks that are all full-time pervs, using the same techniques as—

Owen: It’s the same technique as acting, yeah. All these mofos are freaks.

Mike: Acting, pick-up artistry, magic. These are all—

Owen: Magic is all acting, in a way. To misdirect, you can learn the technique. But then, to truly be great, you have to know misdirection and be able to manipulate people, in a way, through an art form. That’s the same as film to me. It’s like pulling off a great magic trick.

Mike: Also, not being afraid to look like a dumbass.

Owen: Yeah, that I’m not afraid of.

Mike: To pull up with the top hat and rabbit and do the whole thing, that takes ultimate bravery. Acting’s the same thing: you really have to put yourself out there, and embarrass yourself while also using the craft of manipulation and showmanship.

Owen: Say you’re just some guy, Jimmy Schmo or whatever—you’re some nerd, and you know a couple of basic little tricks you picked up off of a toilet seat, and you learn to palm a card. That’s tough. That’s technique. But if you want to apply artistry when you make their card appear, instead of pulling it from behind their ear, next time just throw the fucking deck of cards high in the air and watch them all do 52 pickup, then pretend to catch their card in mid-ass air—because it’s already in your fucking hand and they’ll never know. Easiest trick ever. I’ve done this a million times. It’s great. Even the smartest of motherfuckers will go, “How did you grab that?” Motherfucker, I didn’t. It was in my hand. That’s showmanship, baby. You know what I mean?

Mike: 100%.

Owen: What’s that Hitchcock quote where he says something like—I’m gonna sound like a dumbass mofo if I fuck this up, which I will, inevitably, but it’s something like, suspense is not two people having dinner and then a bomb goes off. It’s when the audience knows there’s a bomb planted underneath the two people and they don’t know when it’s going to go off. In a way, that’s kind of a magic trick too, because we know something that the characters don’t know. There’s a wind-up, like Touch of Evil at the beginning, where so much is going in this crazy elaborate shot you forget about the bomb planted in the car. Misdirection. Then you have to do some acting as a writer and write the dialogue in a convincing way that isn’t corny: “My, isn’t this steak scrumptious, Colonel? Hey, what’s that ticking sound?!” That’s a very hard kind of suspense to pull off in a way that’s original. And then that bomb has to go off at the exact right moment, narratively. Anyway: suspense.

Mike: It’s so bizarre that Houdini, the most famous magician of all time, couldn’t successfully transition to acting and filmmaking.

Owen: There’s one where he gets thawed out of the Arctic that’s kind of cool, but they all suck as movies. He totally flopped. It’s in the Ken Silverman book. I think he paid for them himself, because he was independently wealthy at that point. Maybe that’s not true.

Mike: You’d think this total king could pull off the seemingly doable trick of making a beloved hit movie.

Owen: You’d also think the Jerky Boys, these great prank callers, would make a great comedy, but it doesn’t work out that way, does it? Medium is the message. McLuhan would’ve slapped those Jerky Boys on the wrist. Whack!

Mike: It’s a baffling thing when someone truly hilarious makes a movie and it’s not hilarious.

Owen: I know. Or someone so funny in real life that makes you piss yourself laughing at a bar makes a movie and it’s self-serious. The fuck?!

Mike: It’s the most heartbreaking thing to see.

Owen: An angel dies every time that happens.

Mike: One of the things I love most about your movie is the hyper-specificity of the comedy. Even if you don’t know Fethry Duck, Owly or Tales From the Beanworld, you know it’s something outrageously obscure, and the seriousness with which the characters address these things makes it all the more absurd.

Owen: I haven’t really given a comic book like Tales from the Beanworld a fair shake, I need to buckle down and read the thing, because people now keep asking me about Tales From The Beanworld and I’m not a Beanworld-versed at all. But you get a sense from the name the kind of itch it’s scratching for Miles [Emanuel] and Andy [Milonakis].

Mike: Totally! Even if you have no idea what the hell any of that stuff is, there’s something very recognizable and relatable in seeing Miles and Andy passionately delve into that wormhole. A lot of those scenes in the comic book store reminded me of Kim’s Video, especially in how much of the dynamic is about finding the most bonkers rarities.

Owen: I named The Roxy series Illyse Singer and I put together “Monomania,” because that was actually the diagnosis for that in the 19th century. If you had A.D.D. or O.C.D. you’d would get slapped with monomania back then. It was the blanket term they had in psychiatry. it’s just neurotic, obsessive thinking. Freud was a total monomaniac. So was Hitler. Brian Wilson. You and I definitely have it, but maybe we just have A.D.D. and love dumbass shit.

Mike: Back to magic for a second. I’ve had an idea for a big David Copperfield style trick percolating for a while. I want to skateboard through the Astor Place Cube somehow. I don’t know how to skateboard or do magic, so I’ll need your help.

Owen: We’ve joked for years about doing a Cube movie. We have to do it. The Cube’s great, because it’s a tactile thing and it’s embarrassing to spin it. It’s like Ronnie Bronstein’s Doo-Doo Dollar thing he did as a Frownland intro for a film festival, they just put it on the Frownland Criterion disc too. I bought this fake coin when I was a kid at this store, Abracadabra, which still exists. They had magic tricks and cheapo kind of novelties and rubber Halloween masks of scary stuff, as well as very funny, rude cartoon characters as masks. Beavis, Bart—you can even get a rubber Kenny mask, from South Park.

Mike: Great store.

Owen: Yes. So I bought this coin there, just this stupid, giant plastic coin. It’s like a giant fake dime that’s one of those things that’s impossible to lift up. But who’s gonna pick this thing up? It’s clearly not real money, it’s just stupid. The Cube somehow attracts the same type of person that would struggle with that gigantic idiotic dime or chase Ronnie’s dollar smeared in someone’s makings. Straight-up fools.

Mike: Totally. The Cube rules because a bunch of freaks are attracted to it. They touch it, they fuck around with it…

Owen: It’s a great interactive and extraordinarily dumbass piece of art in that way.

Mike: Speaking of the Doo-Doo Dollar trick, how did you link up with the whole Elara crew? I feel like this is the first feature Josh and Benny have produced that’s not their own.

Owen: It is. I knew those guys when they were coming out of BU and they were doing all the Red Bucket Films stuff. I got involved in that. I remember running around with a boom mic with Josh when he moved back here and was doing a short. We were filming in a Chinese restaurant and didn’t have permission to film there. We were outside, shooting through glass. The two actors were having a meal and paying up. We had this wide shot set up outside the window where nobody knew they were an extra. The restaurant people eventually kicked us out and I immediately understood how movies were made in a way that I had not understood before. Of course, we could’ve asked permission, but a shot-reverse shot of the two actors at the table wouldn’t have been as interesting.

Mike: Yeah. I suspect people think these movies are so giant, but it’s funny when you’re on set and see Benny boom operating and stuff.

Owen: Yeah, yeah. It seems like that’s another way he can pay attention to what’s going on and be engaged. He’s listening in like a CIA op. The way the Safdies would orchestrate chaos within a scene was really interesting. It was fun doing John’s Gone with them back when I was 18. That’s [animator] Charlie [Judkins] across from me in that movie. They put a monkey on his back.

Mike: Nice.

Owen: We were seniors in high school then. I’d crewed on their stuff a little bit and we did an animated trailer for Daddy Longlegs—me, Charlie, Josh and our friend, Sean Donnelly. That’s still up. You ever seen that?

Mike: Shit, I don’t think so.

Owen: I’ve been working creatively with them for a long time and we know each other’s styles. They’ve seen me struggle with a lot of rejection and things over the years trying to make this movie. They stepped in and made it happen, in a way, because no one would give me the money to do it.

Mike: And now, over ten years later, you’re still working together. You love to see it.

Owen: One thing about them is, they’re usually right. If you’re split about something and it could go two ways, they’ll point you in the right direction, because they’ll always choose the more adventurous thing. They’ll encourage that and egg it on and guide you to push things to the limit. We all like to embrace a “certain wrongness,” Ronnie [Bronstein] likes to call it. The more wrong something feels a lot of the time, the better it feels. You know it will burn a little bit.

Mike: It’s like when Harmony Korine was pushing “mistakism” early on. The idea was, there’s a righteousness in working toward mistakes and accidents and you should be striving to fuck everything up at all times. He would describe filmmaking as a mad science rather than a hard science. I love the idea of Hassini developing a thousand ways to blow up Whoppers—that grey area between craft and chaos.

Owen: It’s a great ideology. So, there was this one detail on the shoot where I was right and it was just funny. We looked at all these basement apartments and nothing was really scratching. Nothing’s really feeling like the right thing and I’m looking at what we can get. We find this scary looking basement, but it’s not a basement apartment. It looks like a boiler room. We had to check for asbestos and all this shit, because it was so scary down there. When Ronnie and Josh saw pictures of it, they rightly went, “It’s a little loud,” and they were right. They were like, “We thought you were going to get a basement apartment.” And I was like, “No, no. They live in a boiler room.” And they’re like, “But how are you going to make it look like people actually live here?” That was the fun part. To actually make this fucking nightmare space livable, I mean Jesus. The art department just nailed it: we got to put this together like someone lives here and make it seem lived in and even cozy in some ways, so it’s even more fucked. They built these rooms out of slats that more resemble a horse stable or something. We put in a fridge, a sink, all this stuff.

Mike: A fish tank with no fish.

Owen: This disgusting fucking fish tank was [DP] Sean [Price Williams’s] idea. There’s nothing sadder than someone not taking care of an animal. Anyway, we made it look like people lived there, and we made it look like Joe Franklin’s office. That was the inspiration.

Mike: It’s honestly my favorite part of the movie. And Michael [Townsend Wright], who plays the landlord of the boiler room, actually knew Joe Franklin, right?

Owen: Yeah, since he was 11. He’d visit that office and can do a killer imitation of him, much better than Billy Crystal’s. He does Stan Laurel too. He’d do it at Joe Franklin’s comedy club, county fairs, revival burlesque shows—that kind of thing—and he’s brilliant at it. Michael’s just an incredible actor. He was in a hysterical movie called Charlie Putz that we’re playing the predecessor short to at the Roxy [Putz, 1988, dir. Robert Rothbard].

Mike: Maybe he can do this Stan Laurel impersonation at the Putz screening.

Owen: Oh my God. He’s got to. He can come dressed as Stan.

Mike: Also, if you’ve been cheffing up any new magic tricks, it could also be the perfect venue to bust out the hat and debut something major with a captive audience.

Owen: You know what’s the best magic trick though? Making someone pay attention and care for 80-plus minutes. It’s harder than Houdini’s famous Chinese water torture trick. So, if we can pull that off, I’ll be one happy fellow.