Back to selection

Back to selection

“Extremity in All Forms of Human Experience”: Director David Bruckner on Hellraiser

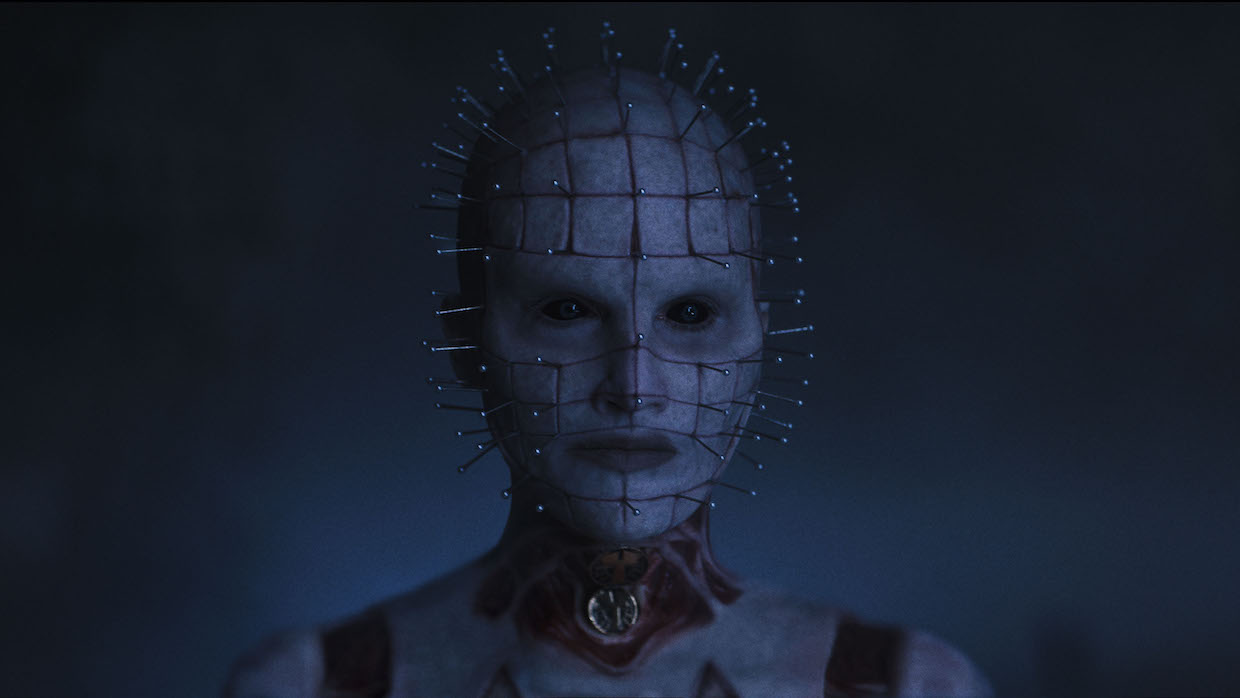

Jamie Clayton as The Priest in Hellraiser

Jamie Clayton as The Priest in Hellraiser In director David Bruckner’s Hellraiser reboot, it’s clear that co-writers Ben Collins and Luke Piotrowski were committed to representing a more faithful version of Clive Barker’s original Hellraiser text, The Hellbound Heart, than continuing any storyline already explored within the long-spanning cinematic franchise. This is for good reason: While Barker’s 1987 Hellraiser (which he helmed due to frustrations with other filmmakers failing to capture his work’s essence) is a renegade horror classic, the subsequent nine sequels are widely considered to be tepid, half-baked follow-ups.

In this version of the story, a young woman named Riley (Odessa A’zion) struggles with drug addiction while mooching rent money and other necessities off of her brother Matt (Brandon Flynn), his live-in boyfriend Colin (Adam Faison) and their roommate Nora (Aoife Hinds). They’re all wary of Riley’s new boyfriend Trevor (Drew Starkey), who she met at a twelve-step program meeting. It’s not long before Riley and Trevor team up to commit a heist for some quick cash, but when they break open a safe stored in a random shipping container, all that they find is a mysterious puzzle box. Unbeknownst to Riley and the rest of her crew, the relic houses unfathomable horrors, awakening demonic creatures called Cenobites that serve The Priest (Jamie Clayton). Re-casting The Priest/Pinhead character as a woman serves a two-pronged purpose: dissuading Bruckner and his team from over-emulating the 1987 film and adhering more closely to the original novel’s description of the entity’s feminine voice.

As the latest filmic installation in a cinematic series that’s lost its luster, Bruckner’s Hellraiser film was largely greenlit due to the success of David Gordon Green’s Halloween reboot, a trend that similarly led to the warm reception of Radio Silence’s latest Scream “requel.” Bruckner follows in the footsteps of these recent efforts, creating a fresh, modern narrative that is tremendously aided by the involvement of the talent behind the originals. In this case, Clive Barker himself signed on as a producer, the first Hellraiser project he’s been involved with over 30 years.

Filmmaker spoke to Bruckner via Zoom ahead of the film’s October 7 Hulu debut, a conversation that offered insights into working with horror auteur Clive Barker, redesigning the iconic Cenobites and the film’s warm reception at this year’s Fantastic Fest.

Filmmaker: So, you directed the film from a script by Ben Collins and Luke Piotrowski, who you’ve collaborated with in the past. They also co-wrote The Night House, and adapted your V/H/S segment into a script for the film Siren, which you executive produced. Can you speak about how this extended collaboration came about, and why you work well together?

Bruckner: Well, we became friends initially. We had the same manager, Nate Madison. So when I first moved to LA, I met Ben and Luke, who are fellow Atlantans like myself. We just started to talk story, and there was an opportunity to take my V/H/S short and turn it into a feature film, and they had a really great idea for how to do that. I was originally going to direct, but then I had this other thing that was going on—a Friday the 13th movie, which didn’t happen—but Gregg Bishop brought [Siren] across the line, and he did a lovely job.

After I finished a feature that I shot in Romania and posted in London, I’d been gone for a year. When I came back, Ben and Luke had a script that they had run by me a couple years previously, and that was The Night House. I read it and just completely fell in love with it. There was a period where I ran around town and anybody I would meet, they would say, “What are you into?” And I’d say, “Well, there’s this movie that no one has the guts to make.” I was very fortunate that [producers] David Goyer and Keith Levine really took to it and fought to make that happen. So we had a great experience with The Night House, and the entire team transitioned into Hellraiser right around the end of 2019.

David Goyer wrote a treatment for Spyglass [Media Group], who had recently acquired the rights to Hellraiser. Naturally, they went to Ben and Luke, partially because The Night House had some Hellraiser-esque themes. It was loosely based on a Hellraiser pitch that they had from about a decade prior. They brought the script to life while I was in post on The Night House. When we got done with that movie and settled into April 2020, early pandemic, I finally got to read the [Hellraiser] script and thought that they had pulled off the impossible. They found a way to bring Hellraiser into being at a time where people might have been pretty risk averse to the franchise.

Filmmaker: As I’m sure you’re aware, the original Hellraiser is a queer horror staple: The leather, the BDSM, the sensual investigation of pain and pleasure. Obviously, your film features LGBT characters and cast members, but I’m curious how Hellraiser’s queer legacy impacted the overall vibe of the film?

Bruckner: It was something that we really wanted to get right. The casting was something that felt very obvious to us, but we also had to modulate it for this particular story. Not every story in the Hellraiser universe is going to be the story of Frank and Julia, necessarily. So one of the things that I thought that was really smart that David, Ben and Luke had done was expand the mythological possibilities of what the box could provide. It really was about extremity in all forms of human experience, it wasn’t just the pleasure-pain threshold. I thought that opened up a lot of different doorways to interpret what the film could be about. I felt that there were fragments of those pursuits throughout the other films in many different ways. It’s about the extent of knowledge, but it’s also about love—about the ability to coalesce with another human being to an absurd extremity.

There’s the idea, of course, of sensation and pleasure pursuits. But there’s also the idea of resurrection, which is about permanence. It’s about existing internally, and then about power, which felt appropriate for the domination instincts of the Cenobites. We had to be true to this story first and foremost. That said, there’s a lot in the original films on offer where the kink community is concerned, and we tried to encode that as best we could. While we’ve lost the black leather, some of that was simply because of what we thought the conversation was about these days. [Kink] has found its way into popular fashion in a lot of ways. You’ve seen those images replicated over and over again, and we just thought that we could find a different approach that might feel, on some level, as transgressive as the original.

Out of that came the idea of the Cenobites being body modified to such an extent that they kind of become their own leather. They’re still fashionable, there’s still a glamorous aspect of them, but it’s quite repulsive that they are fully nude and they’re completely committed to the same pursuits. So we tried to get those visual ideas into the designs, just in a different way. I’d say the Cenobite torture scenes, to me, have a very sexual component in the way they’re employed. I don’t want to give anything away about the sequences, but there’s a lot of play involved.

Filmmaker: Expanding on how the film approaches pain, pleasure and sensuality, I think it’s interesting that when Riley first sees the Cenobites, she’s relapsing and has her high interrupted by their visage. How did you want to communicate the extremes of physical sensation, how we’re constantly oscillating between so many polarizing feelings and sensations?

Bruckner: I think the original movie is very much about possession, and a lot of people have mentioned that there’s an aspect of self-discovery. Certainly that’s the metaphor of opening Pandora’s box, discovering something that’s inside you that you were afraid of in some way or another. The addiction subplot, and the themes inherent in that, are for me an adjacent conversation to that experience. It’s about someone who doesn’t have a healthy relationship with their desires. They’re using them to cope, to escape. Riley is someone who I think feels very anxious in her life and has developed an unhealthy way—as most of us do with addiction—to relieve herself of the burden of being by getting carried away by all of those delights, whatever they may be.

And we like to say that Riley was drawn to anything shiny, whether that be this guy Trevor, or a bottle of pills or a mysterious puzzle box. Anything that allows her to lose herself. But there’s consequence in that action. That’s what drives the movie, is her paying a debt for that, trying to undo what has been done. It felt like a relevant conversation to have in the world of Hellraiser. It allowed us to take the perspective of her experience in that state of mind. So when she’s playing with the puzzle box, when she’s being tempted by the Cenobites, there’s a holy sensibility to it. There’s a magic to it. She’s being lost. It’s not all played for frights, sometimes it’s played for allure, and that felt appropriate to us.

Filmmaker: Hellraiser is one of a few recent re-imaginations of Clive Barker’s work. There was an adaptation of Books of Blood, which was similarly made for Hulu, as well as Nia DaCosta’s recent Candyman reboot, with the original film having been inspired by his short story The Forbidden, which is funnily enough featured in the Books of Blood anthology collection. What did it feel like to have Clive’s seal of approval on this project, and how did his producer status help shape the film?

Bruckner: When we started the project, Clive wasn’t yet on board. So it meant a lot to us, obviously, when he decided to get behind this—when he saw what we were doing and recognized the effort that was going into it. I was actually in Belgrade getting the movie going when he first came on board. He called me and from the jump we just leapt into what was a really marvelous conversation about this film and about where it could go. I think he recognized from the beginning that we were going to have to do our own thing. I mean, the original film, to me, is a masterpiece of horror. There’s nothing like it. Part of the way we showed our regard for that was to not try and emulate it beat for beat. To agree, hopefully, with the audience and horror fans that it can’t be done and it ought not be done. For us to forge a new path is really the only respectable way for us to continue to have Hellraiser in our lives in new forms. Clive was very supportive of that. He played a role, like any good creative producer, which was to push, prod, encourage and seek to understand. I spent many, many long nights on the phone sharing artwork and discussing the script [with him]. He was fascinated by the differences, supportive but at times quite challenging. He played that role in post as well. I’m really, really grateful for his time. He was very generous.

Filmmaker: The reaction out of Fantastic Fest was generally really positive, which must have been exciting for the latest entry in a franchise that’s been plagued by bad sequels and spin-offs. Can you speak about the experience of having the film resonate with the broader horror community, particularly in an in-person festival environment? Though The Night House was really well received, it must have feet bittersweet to not have that extended, tangible indicator of audience reaction.

Bruckner: Well I didn’t get to experience The Night House as released because we were making Hellraiser. I only get to see The Night House once with an audience, which was the first night it premiered at Sundance. As a filmmaker, those are always terrifying, humbling experiences, because you have no idea where you’re going to land. When you spend the amount of time and energy that you do with a film, you get to a place where it’s very difficult to see. So you go from being in a very dark room with something that you’re far too close to have perspective on, then you get pushed out on stage in front of a large audience. If it works, their often audible reactions—especially in this genre—are delight to hear. [These reactions], I find, remind me of what we sought to do in the first place. I’m reminded that, “Oh yeah, this works.” Or, “Oh yeah, that’s funny.” That this is a moment when you could hear a pin drop in the room. So that level of engagement is really thrilling to be present for when it works.

Hellraiser‘s a streaming movie, so everybody’s going to experience this at home, hopefully in the dark with the volume cranked. But we knew that we wanted to premiere it in public at a genre festival, especially because Hellraiser is so complex, nuanced and niche in many different ways. We wanted it to be revealed to an audience that understands what Hellraizer is and loves it. I’ll say that at both Fantastic Fest and at Beyond Fest, those were really fantastic, energetic screenings. The audience gets it. They get the humor, they understand the in-jokes, they know when we’re having fun, they know when we’re being serious. It was really exciting to bring it home with a group of people that loves Hellraiser as much as we do.

Filmmaker: Now that you’ve had your hand in helming original horror concepts and re-imaginings of established IP, what were the distinct challenges and benefits of working within both realms?

Bruckner: I firmly believe that filmmaking has to be personal, or else you have nothing to offer. Whether it’s an original story or IP, you’re always looking to dig into something that you understand on a gut level. The difference is that with IP, you do have to double-back quite a bit [in order to gain] a broader understanding of what something is. We tried to follow our passions where this story was concerned, but also pay homage to what had come before us. That can be tricky, because I think you can spin too many plates. In Hellraiser, there’s a lot of different things, and we can’t get it all into one movie necessarily. We know there’ll be different attitudes about what it ought to be or what we could have done. At the end of the day, we just had to be true to what we were doing and what we felt was right and lose ourselves in that. I will say there is some apprehension in taking on IP where that’s concerned, because you really want to get it right. So it’s been great to hear the responses and feel like people are getting it.

Filmmaker: May I ask if there are any future or upcoming projects on the docket for you?

Bruckner: At the moment, not really. I went straight from The Night House into Hellraiser, so it’s been a very busy few years. I’m very much looking forward to a little bit of time to read, watch movies, experience life a bit and hopefully come back to this with some new experiences myself. I’m gonna take a little time off.

Filmmaker: Do you think that when you do come back, you’ll find yourself in the horror genre again?

Bruckner: I don’t think I’ll ever bore of horror. I mean, it’s the only place where we’re permitted to be surreal and a bit weird. There are other things that fascinate me—you know, science fiction was one of my first loves—and I wouldn’t mind trying my hand at long-form and television. But we’ll see what happens.