Back to selection

Back to selection

“The Consequences of Putin’s Playbook”: Marusya Syroechkovskaya on How to Save a Dead Friend

Marusya Syroechkovskaya's How to Save a Dead Friend

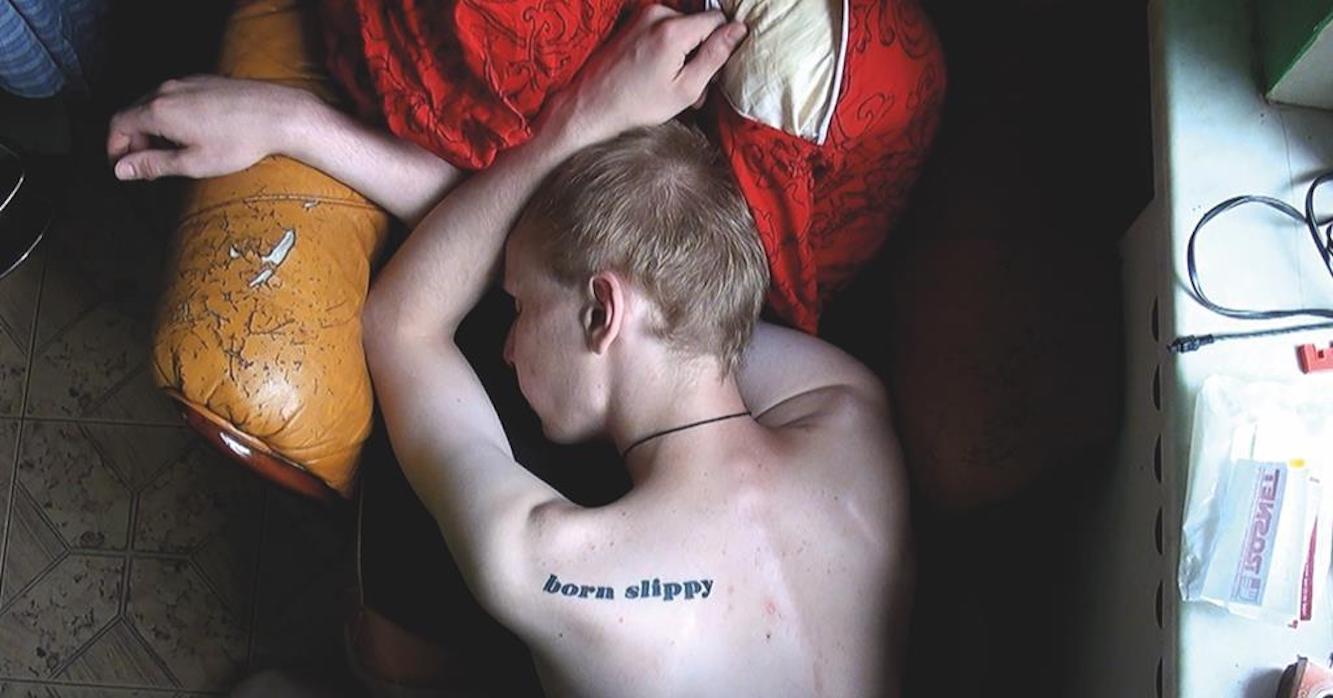

Marusya Syroechkovskaya's How to Save a Dead Friend “Russia is for Russians!” goes the far-right rallying cry. To which Marusya replies, “Bullshit. Russia is for depressed people.” She should know: Moscow-born Marusya Syroechkovskaya spent a dozen years turning her camera (multiple cameras, really) on herself and her co-credited cameraperson and best friend (turned lover, turned husband, turned ex) Kimi Morev. The two met as suicidal teenagers in their nation’s capital in the aughts, both part of the spiraling “silenced generation” under Putin. They shocked one another by deciding to stick around for a spell to see how their—and perhaps their antiauthoritarian compatriots’s—story would end. (That said, the soulmates didn’t actually notice the 2000s come to a close. As the director laments, “It’s just like they morphed into a bad trip.”)

Surprisingly for a film that takes an unflinching look at mental illness and addiction in the “depression Federation”—and is tellingly titled How to Save a Dead Friend—the tale is one of unbridled joie de vivre as much as it is about ultimate self-destruction. Indeed, the doc moves as swiftly and headily as its post-punk and grunge-heavy soundtrack. It’s also thrillingly infused with kaleidoscopic imagery that unexpectedly brings to mind the work of Gregg Araki. (In addition to the New Queer Cinema icon, Syroechkovskaya has also cited Harmony Korine and the artwork of David LaChapelle as touchstones.) Through the drinking and snorting, injecting and cutting, remained an eternal love that would tear them apart. (Naturally, Joy Division also figures prominently in their lives, as evidenced by the cat they decided to name Ian.) This feature-length resurrection also persists, the sweetest of requiems for a futureless generation.

A few days before How to Save a Dead Friend’s DOC NYC and IDFA debuts, Filmmaker reached out to the award-winning filmmaker, visual artist and oppositional voice in exile, who fled her homeland in March as the Russian hammer came down.

Filmmaker: This film is such an intimate journey into the lives of two people, one of whom is not able to have any say in the project. How did you decide what footage to include or edit out in the final cut?

Syroechkovskaya: I made this film out of love for someone I couldn’t save. I tried to save a memory of Kimi; I didn’t want his voice to be lost and gone. I believe that you are not gone as long as people remember you.

I didn’t want to include any footage where Kimi is totally out of it, consumed by drugs or looks defeated. This is not how I want people to remember Kimi. I wanted audiences to see him with my eyes, to see a person I loved very much, who had his strengths and flaws like every other human being.

Filmmaker: Though it’s not common for documentary filmmakers to cite Gregg Araki as an inspiration, his influence on How to Save a Dead Friend is indeed apparent, as is Harmony Korine’s. Were there specific films and bands you looked to as a template? What other forms of media guided your vision?

Syroechkovskaya: I wanted to save the time, space and things that formed Kimi and me as we were growing up. How to Save a Dead Friend is also a tribute to the films of Gregg Araki (the “Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy,” but mostly Nowhere), Harmony Korine (julien donkey-boy) and the artwork of David LaChapelle. It’s also a tribute to lots of music—from post-punk and grunge, to emo and witch house—and to Windows Movie Maker transitions, early web aesthetics and internet forums, when the internet wasn’t yet controlled by corporations and censored by the government, a place where you could freely express yourself and find belonging, occupying your dial-up for hours.

Filmmaker: Having read that there are a whopping 700 cuts in the film, I’m quite curious to hear about the editing process, including working with your Syrian-born director/editor Qutaiba Barhamji, whose work spans multiple languages and genres. How did you two meet, and how did you approach the daunting task of weaving together footage shot with so many different cameras?

Syroechkovskaya: Qutaiba and I met while he was working on a mid-length project I was producing. I knew right away that I would love to work with him on my future film. What I like about his approach is that he always works towards the film the director wants to make. He talks a lot with directors, then it’s about translating the director’s vision during the editing process. I actually approached him before there were any co-producers or financing in place. I was thrilled when Qutaiba told me he fell in love with this project and agreed to work with me.

The main creative challenge was that the material I had wasn’t meant to become a film while it was being shot. There are so many different formats, cameras, mediums and frame rates. In the beginning, we had no idea where to start or how to approach the material. Honestly, that’s what I like about working on creative documentaries, and I find it very exciting. We experimented a lot—with time, rhythm, dramaturgy, and with how to build the distance between me as the director and me as a character.

Another challenge was COVID, of course. It took us six months to edit the film. Qutaiba was in Paris and I was in Moscow, so we edited almost the whole film through Skype. That wasn’t an easy task. You know how you cannot interrupt each other on Skype because then no one hears anything? So, we couldn’t really argue. Luckily, we had our last editing session in person in Norway—and we had enough time to argue, cry and interrupt each other. That last session was so much more productive!

Filmmaker: Since I’m not familiar with the Voice of Sisyphus Image Sonification (VOSIS) app that you used, I’m very curious to hear more about that as well. How did you connect with its developer Dr. Ryan McGee, and how did you employ it throughout the film?

Syroechkovskaya: I had this idea of transforming videos of Kimi into music and sounds. I thought of it as a poetic way of imagining what happens to us when we are gone. I would like to imagine that Kimi turned into music. I also felt that this is a metaphor for filmmaking in general—you touch something from a distance, through a screen, and from this touch something else is being born.

I knew I needed some sonification program, so I started researching online. That’s how I came across VOSIS. I liked the interface and the sound of it, but it was built only for live video and still pictures. So I contacted Ryan, the developer, and told him about my film. I asked if he would be willing to share the source code with me so that I could make some adjustments to the app. Though he wasn’t comfortable with that, he really liked the project and instead offered to help me with it. Together we experimented a lot with how the app looks, how it works and what features it has. You can actually download a free version of VOSIS at the App Store, and there’s also a pro version that you can buy.

Filmmaker: Though you had to flee Russia this past March, I’m guessing that you are still engaged with the opposition movement both there and abroad. Has your activism work increased or perhaps changed in any particular way? Are you using How to Save a Dead Friend as a platform?

Syroechkovskaya: I travel with my film a lot, and I feel it’s my responsibility, especially now, not to stay silent. So, I try to use my film as a platform to create further discussion.

How to Save a Dead Friend shows the consequences of Putin’s playbook to isolate the Russian people. From the very beginning, Putin was working on how to control a huge populace so he could do what he wanted. One of these methods is gaslighting the entire country by isolating them from the rest of the world. What this film can help explain is what such isolation from the global community can do to a populace—and what it can do to new generations. I believe that sometimes a film can be more straightforward than words. Sometimes, all you need is to see what life under a dictatorship feels like to know that there’s no future in any totalitarian state.