Back to selection

Back to selection

From the Archives: Mike Kelley Interviews Harmony Korine

Mike Kelley, who passed away this month, contributed to Filmmaker once, in 1997, when he interviewed Harmony Korine about Korine’s debut feature, Gummo. From our archives, here is that interview.

With a poetic, impressionistic take on film narrative, a visual style incorporating everything from elegantly framed 35mm to the skuzziest of home camcorder footage, and a startling mixture of teen tragedy, vaudeville humor, and sensationalist imagery, Harmony Korine’s first feature Gummo is perhaps the only recent film whose artistic strategies draw as much from visual art as the film world. (A gallery installation of work from Gummo opens at L.A.’s Patrick Painter gallery in late September). We were thus very happy when Mike Kelley – one of today’s most essential and subversive artists – agreed to interview Korine on the eve of a major gallery installation in Copenhagen. Like Korine, Kelley blithely shreds conservative notions of high and low art as he mounts major gallery shows, designs album covers for bands like Sonic Youth, and plays in Destroy All Monsters with Thurston Moore. In fact, one of the band’s songs, “Mom and Dad’s Pussy,” opens Korine’s film.

With a poetic, impressionistic take on film narrative, a visual style incorporating everything from elegantly framed 35mm to the skuzziest of home camcorder footage, and a startling mixture of teen tragedy, vaudeville humor, and sensationalist imagery, Harmony Korine’s first feature Gummo is perhaps the only recent film whose artistic strategies draw as much from visual art as the film world. (A gallery installation of work from Gummo opens at L.A.’s Patrick Painter gallery in late September). We were thus very happy when Mike Kelley – one of today’s most essential and subversive artists – agreed to interview Korine on the eve of a major gallery installation in Copenhagen. Like Korine, Kelley blithely shreds conservative notions of high and low art as he mounts major gallery shows, designs album covers for bands like Sonic Youth, and plays in Destroy All Monsters with Thurston Moore. In fact, one of the band’s songs, “Mom and Dad’s Pussy,” opens Korine’s film.

Korine: So how did you like your song? It starts the movie with that Super-8 image we kept repeating of the girl in the front of the trailer – I just knew that song would fit that image.

Kelley: I guess I couldn’t tell the gender of the kids.

Korine: I think they were little girls. We were just driving around – that’s how I got a lot of that footage, the Super-8 and video stuff. Just walking around neighborhoods, walking up to people.

Kelley: How much footage do you have of that kind of material?

Korine: I could probably make another two movies with the excess footage. In a strange way, I want to get to a point where the next two movies are even more random and more incidental without them being overly arty. I just want things to become a succession of scenes, images and sounds. I was thinking about [the gallery show] – the problem you run into doing multimedia projection is that a lot of the time, the style takes over; it threatens and reduces the content. It becomes almost like a music video – mixing all these forms for no reason.

Kelley: A post-modern pastiche?

Korine: Exactly. It’s so boring, like a Sprite commercial. With Gummo, I wanted to invent a new film. I wanted to make a movie where nothing was done for any purpose other than that I wanted to see it. I wanted to make the first film that would hopefully play in malls in which you would see images with very little justification other than that these were things that I wanted to see. That’s why everyone gets upset with the girl shaving her eyebrows.

Kelly: People don’t like it when you use retarded people.

Korine: Even though I had met her months before, played Donkey Kong with her, and she had no eyebrows then. That was her style. We tried really hard to have images come from all directions. If I had to give this a name, I’d call it a “mistake-ist” art form – like science projects, things blowing up in my face, what comes of that.

Kelley: Something alchemical?

Korine: Exactly. When we switched forms, when the film went to video, Hi-8, or Polaroids – I wanted everything to feel like it was done for a reason. Like they shot it on video because they couldn’t get it onto 35mm, or they shot it on Polaroids because that was the only camera that was there.

Korine: Exactly. When we switched forms, when the film went to video, Hi-8, or Polaroids – I wanted everything to feel like it was done for a reason. Like they shot it on video because they couldn’t get it onto 35mm, or they shot it on Polaroids because that was the only camera that was there.

Kelley: Did you do many effects in post-production? That shot of a cat eating – the image was phasing.

Korine: That’s what I mean by “mistake-ist”. There was a script, but as a screenwriter, I’m so bored with the idea of following a script. I felt like I had the movie in the script, so we shot the script but then shot everything else and made sense of it all in the editing process. That cat tape was a tape that a friend of mine had given me of him doing acid with his sister. They were in a garage band, and there was a shot of their kitten. That [phasing] was an in-camera mistake. The editor, Chris Tellefsen, caught it and said, “That’s kind of interesting.”

Kelley: A lot of the movie is about framing things that are basically performative. Here’s a kind of action, let’s let people go with it. The tap dancing scene, the kids shooting the boy with the bunny ears –

Korine: Or the scene where the brothers beat each other up.

Kelley: But other scenes are more pictorial.

Korine: We go from scenes that are completely thought out, almost formal, scenes that resonate in this classical film sense, and then we go to other scenes where it’s like, total mistakes, stuff shot on video where the kids forget there’s a camera there and say that they “hate niggers.” I felt like shooting each scene on its own terms and then making sense of it afterwards. And I felt that the styles would blend, that there would be a cohesiveness.

Kelley: There’s a cohesiveness for a number of reasons. One is that, o.k., despite the surreal element, the film depicts a milieu that would allow for that. It’s not unusual for people to do odd things in reality, so you can have a realist film and have strange things happening, and it doesn’t seem surreal. In traditional narrative film, where there’s a shift in style, like when the image gets fuzzy, you see it as a shift of point-of-view, like a dream sequence.

Korine: I hate that shit! That’s why I hate Fellini, because it’s all like a cartoon to me. It’s not based in any kind of realism. I don’t care about it if it’s not real.

Kelley: That’s funny. If I had to compare you to anybody, I’d compare you to Fellini.

Korine: And he’s someone whose films I can’t stand. The films of his I like are the more realistic early films.

Kelley: But he uses non-actors, it’s biographical, there’s stylization. It’s just the stylization is really overt.

Korine: But it’s like surrealism, and I was never so interested in surrealism. This odd thing that I do – it’s like surrealistic realism. Everything seems like it’s normal, everything is presented as if it’s 100 percent true, but at the same time, a lot of the stuff that goes on is kind of outrageous, made up.

Kelley: How do you think the realist element comes through with all your playing with style? I think people could mistake this as being like MTV. What would you say to someone who says, “This isn’t realist. This doesn’t follow traditional realist tropes.”

Korine: I’d go after their ass!

Kelley: It seems to me that you could only have a feature film like this post-MTV. Otherwise it would be seen as an avant-garde film.

Korine: I don’t know. Look at Griffith, what he was doing. The commercial movies now, I see so little progress in the narrative form unless you’re talking about Oliver Stone, who to me is making films that are completely empty and all about style. I was talking to my friend Christopher Woole about the difference between style and substance. He said, “You should never worry about that because substance is style.” Most art makes me sick because everything has become like solving math problems. Everyone is working from the wrong direction, from the outside in. Approaching Gummo like a piece of art that entertains, I wanted it to be more from the inside out, more about going with my obsessions. I wanted to create a cinema of obsession, a cinema of passion.

Kelley: The night before I saw your movie, I saw Slingblade.

Korine: Oh, I hate that film.

Kelley: But there’s a whole bunch of white trash movies in the last ten years. There are the pathos ones like Slingblade, and then there are the freak show ones. It’s even found its way into fashion photography. And I saw this Wendy’s commercial with people who live in a trailer. If I’m looking at Gummo and I’m looking at this other stuff, structural questions are important because otherwise your film becomes about “white trash, our new outsiders.”

Korine: In Gummo, I wasn’t interested in any kind of white trash chic. It was about going back to where I grew up, casting kids I grew up with, like the black dwarf – I went to high school with him. I just wanted to show these kids. Kids beating each others brains in. I wanted to show what it was like to do crank or sniff glue. I didn’t want to judge anybody. This is why I have very little interest in working with actors. [Non-actors] can give you what an actor can never give you: pieces of themselves.

Kelley: I really like that about the film. When people were acting in a way that was completely unnatural, they were real people acting unnatural. That reminded me of the best aspects of the Warhol Factory system.

Korine: You know who I love and who no one really knows about? Alan Clarke, the British director. He’s a real influence. He did Scum, Made in Britain, and this film Christine about a girl growing up in council flats with size 14 feet. She walks around with a cookie tin under her arm and hooks her friends up with dope. She’ll go into houses and kids will be there with a box of Ritz crackers on the television. You’d have these really long tracking shots of her walking. The film was just sort of about what her days were like. And he used real people or people who seemed right. He did this other film I like, Elephant, which is just 16 separate executions, one after the other. There are all these steadicam shots. You see a hit man walking through a gymnasium, walking up stairs and corridors –

Kelley: Are these first-person POV shots?

Korine: Exactly. And then [the hit man] would shoot the janitor, and he’d fall on a pile of jockstraps. But the intention wasn’t comedy. After he died in 1988 of cancer, there was a retrospective of Clarke’s work at MOMA. There were only about ten people in the audience. I was watching Elephant, and in the beginning it was a little disturbing. And then I started to find humor in the repetition – watching some Indian carwasher get his hand blown out on a squeegee. I start cracking up, and this British bastard in front of me turns and says, “Don’t you know what this represents? This is the IRA, you son of a bitch!” He wanted to kill me. I liked that idea. He thought it was about the IRA, and I thought it was about Ritz crackers.

Kelley: You talk about inebriation a lot. Are you trying to make a movie that’s a kind of visual inebriant? I wasn’t bored watching the movie, even though you couldn’t say there was a plot. But, afterwards, I didn’t know how much time had passed. I was in a half nod looking at people whose lives are in a half nod.

Kelley: You talk about inebriation a lot. Are you trying to make a movie that’s a kind of visual inebriant? I wasn’t bored watching the movie, even though you couldn’t say there was a plot. But, afterwards, I didn’t know how much time had passed. I was in a half nod looking at people whose lives are in a half nod.

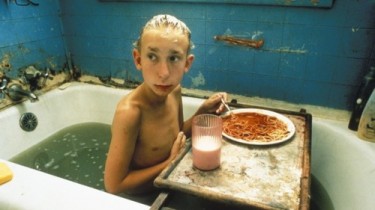

Korine: I wanted it to be more of a tapestry, so if that was the effect of watching this kind of tapestry of people . . . I was as concerned as you looking at the dolls strung up when the kid gets his hair watched.

Kelley: I loved the art direction.

Korine: It was very minimal.

Kelley: A lot of it was found but in certain cases, you must have had to play with it some. I couldn’t believe some of those houses.

Korine: There were a lot of things going on in those neighborhoods, things like underground prostitution. In that house where you see piles of shit everywhere and the bugs run out of the painting – not only was all that stuff there, but we had to take out stuff to be able to put the camera in the room! The [family consisted of] three generations of packrats, and they were really into collecting their pizza boxes, heaping them up. I found a piece of a guy’s shoulder in a pillowcase. A teenage girl was living downstairs and she had wallpapered her room with Teen Beat posters of Jonathan Taylor Thomas. It was incredible – the most amazing shrine of teen sex. But Jonathan’s mother said she didn’t want to be involved in any way with the makers of Kids. We got denied permission to use a lot of stuff. Like, there’s this scene where this guy talks about rumors. The studio said I couldn’t say anything about anyone who’s alive unless the person gives me permission. I wanted to say that Raquel Welch had her bottom ribs surgically removed but we had to redo it saying Marlene Dietrich.

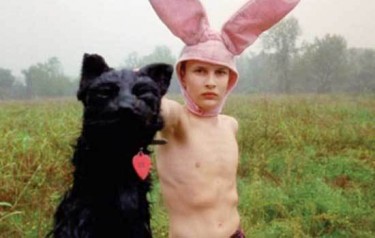

Kelley: There are certain motifs that run throughout the movie, sort of structural loops that hold it together. One of them is the recurring figure of this bunny boy, the other is the cat hunting. Were those elements planned from the beginning?

Korine: Oh yeah, that was in the script. The movie is much more scripted than you would think. It’s about 75% scripted.

Kelley: So the script would have a scene that would be imagistic, and another section would say, “Now there’s going to be a party.”

Korine: No. I wrote those scenes out perfectly. Then we would ask the actors to do them without me imposing my ideas of how they should be blocked. Most of the time, it was a different way than I dreamt it. In some cases, it was worse, and we’d go with my [blocking]. In other cases, it would be really exciting, and I’d change the scene spontaneously.

Kelley: There’s a certain milieu that’s pictured, but [the film’s] not really of that milieu. You’re using black metal [music on the soundtrack] but the kids are wearing Dio t-shirts and are cutting “Slayer” into their arms.

Korine: It goes further than that. There’s a whole vaudeville subtext. Kids in Dio t-shirts doing Jimmy Durante routines. That stand-up comedy routine Tummler does on the glass table after he goes with the whore – that’s like a Henry Youngman monologue.

Kelley: Calling the cat Foot Foot, like the Shags song. That’s a funny inside joke.

Korine: Oh, there’s millions of those.

Kelley: One thing I wanted to ask – are Dot and her sister modeled after Cherie Curie?

Korine: Oh, completely – that was a total theft! I wanted that in there, but I didn’t want it to not make sense. I wanted [the girls] to adapt to their environment. [The film] is a total mix of history and pop, a making sense of pop. To me, that is what is always lacking in film – there’s never a relationship to pop culture. America – and I’m not talking about New York and L.A. – is all about this recycling, this interpretation of pop. I want you to see these kids wearing Bone, Thugs, and Harmony t-shirts and Metallica hats – this almost schizophrenic identification with popular imagery. If you think about it, that’s how people relate to each other these days, through these images.

Kelley: That’s the thing I liked best about the film. It showed how all these Hollywood clichés about middle America are just completely wrong structurally. When you see Hollywood movies that show these white trash milieus, they make them too uniform, not as weird as they are. That’s why I hate all this neo-pop art. It makes too much sense.

Korine: You said it. It lacks this kind of cohesive schizophrenia. I like the idea of seeing kids who still have Ratt tails and a tattoo of Janet Jackson on their forearm.

Kelley: Wearing a shag hairdo. It makes no sense.

Korine: Yeah, but it makes sense to them. It goes to this home-school kind of aesthetic I wanted to run through the film. For me, Dot and Helen – I wanted them to seem like home-school kids. You know, those kids who never had any true interaction with large groups. I love that – kids within their own home sort of guessing and coming up with these hipster things. They almost make a home-school hip language. I wanted this kind of inbred vernacular. I want to avoid any of the easy answers.