Back to selection

Back to selection

“Everything Looks Better if You Throw Some Dirt and Blood on It”: Robbie Banfitch on The Outwaters

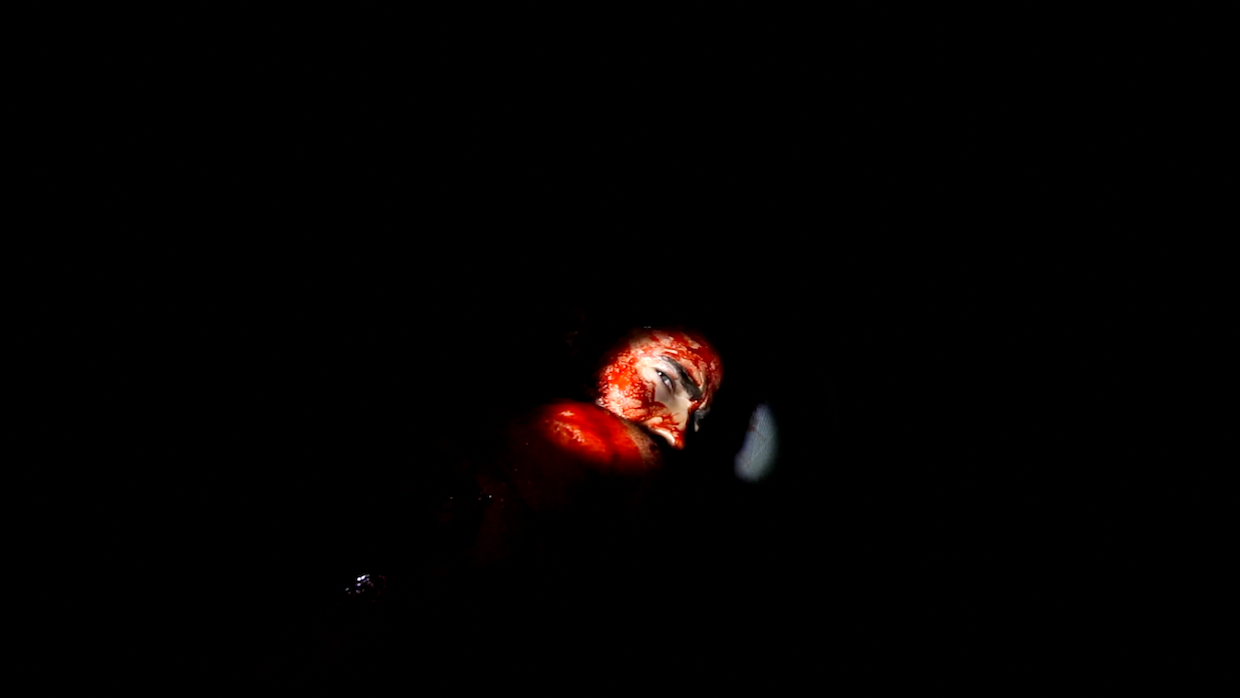

Scott Schamell in The Outwaters.

Scott Schamell in The Outwaters. Microbudget independent horror is certainly having a moment. Kyle Edward Ball’s experimental haunted house flick Skinamarink has grossed $2 million to date on a $15,000 budget, and 17-year-old YouTuber Kane Parsons will turn his lo-fi viral series The Backrooms into a feature film for A24. Similarly reinvigorating a long-reliable medium for first-time horror filmmakers, Robbie Banfitch’s found footage gem The Outwaters defies genre expectations while showing seasoned gore hounds exactly what they want to see (and perhaps a few things they’ll probably wish they hadn’t).

The film’s writer, director, cinematographer, editor and producer, Banfitch also stars as Robbie Zagorac, the camera-wielding member of a friend group that ventures into the remote Mojave desert to shoot a music video for aspiring singer-songwriter Michelle August (Michelle May). As they camp below the stars, the group slowly becomes involved in eerie and otherworldly phenomena. The audience only sees what unfolds via three memory cards retrieved by police after their collective disappearance, allowing viewers to act as speculative detectives for a mystery that becomes increasingly surreal and metaphysically confounding. While the first two memory cards serve as an endearingly aimless chronicle of a low-key roadtrip, this extended hangout allows us to connect with additional travelers Angela (Angela Basolis) and Robbie’s on-screen brother Scott (Scott Schamell) as well as the pair’s mother (Leslie Ann Banfitch, the filmmaker’s actual mother). This makes their inevitable suffering all the more torturous to sit through, particularly when desperate voicemails from Leslie are sprinkled throughout the narrative. Yet Banfitch is clever when it comes to revealing blood and guts on camera, as pitch black darkness and sparse illumination from flashlights obscure much of the group’s initial descent into peril. Depictions of bodily harm and maiming only become overt as the maddening landscape—and whatever resides within it—begins to take over Robbie’s very psyche.

I spoke to Banfitch a week before The Outwater‘s limited theatrical release from Cinedigm and Bloody Disgusting. Our conversation touched upon our shared New Jersey heritage, the tangible creepiness that Banfitch and his crew felt during their Mojave shoot and our mutual adoration for Harmony Korine’s indie opus Gummo. Find where to catch Banfitch’s brutal, cosmically horrifying vision here. Additionally, an exclusive streaming window will be made available via Screambox Films later this year.

Filmmaker: Like yourself, I’m also originally from New Jersey. I think that the characters’ origins, namely Angela who so thoroughly evokes the essence of a “Jersey girl,” make for really interesting parallels here, particularly considering the contrast of Jersey’s bountiful moniker being the “Garden State” with the inhospitable, arid landscape of the Mojave. Can you tell me how you worked to portray their outsider status amid the scorching desert? Also, I know you’re based in LA now, but how many of the cast members, if any, actually came from Jersey to participate?

Banfitch: Ang and I are originally from Jersey, so she’s the only one who traveled for the shoot. There were lots of impromptu moments. I mean, I’ve known Angela for a long time, and we do the Jersey shore thing. [laughs] We actually had a YouTube video where Ang talked about pickles and we had thick Jersey accents years before Jersey Shore came out. I just really thought that character would be great to plop into the Mojave in a movie. But I would say it wasn’t really planned or thought out, it was an instinctual choice. As far as the landscape goes, a lot of it was discovered while filming.

Filmmaker: I want to ask a bit more about the cast, which consists of your real-life friend group and mother. Are any of them trained or aspiring actors?

Banfitch: I don’t know that anyone is trained. I studied acting alongside filmmaking when I was at the School of Visual Arts. I also studied acting at Black Nexxus, which Susan Batson runs. She is wonderful. Other than that, I don’t believe any of us have taken acting classes. Ang has been acting in my stuff for a long time, and we did lots of improv videos more on the comedy side. I also believe Scott’s taken a couple acting classes in the past for fun.

Filmmaker: Your mother’s voicemail is intensely chilling, as are Angela’s anguished wails for her own mother when the bloody phenomena begins. I know the film wasn’t scripted, but how did you direct each actor to give such emotionally intense performances? How many takes were often necessary to yield the perfect result?

Banfitch: Actually, it’s Michelle who’s screaming for her mother, but it’s pitch black and her screams are mixed with Ang’s, so it makes sense to be [confused]. I knew that Ang could give that kind of performance in general, because we’ve done similar things in the past with earlier films. We also just talked as a group about what people in real pain might sound like, because there is a difference between horror movie screams and if you watch videos of bad things actually happening. Because these are my close friends, I knew that they would all be able to reach that [state] and there wasn’t any sense of like, “This is embarrassing.” I would say we usually got it after one to three takes.

Filmmaker: I’m curious if there was ever a lingering uneasiness or spookiness on the shoot. I know you’ve said that you incorporated your cast’s road trip to shoot the film into the fabric of The Outwaters itself, but you have to admit that “a group of friends shooting an independent film in the desert” is an eerie enough premise for a found footage horror film in and of itself.

Banfitch: There were moments where I was totally creeped out and scared while camping in the desert, but it had nothing to do with the movie. I would’ve been just as scared if I had been there not making a movie. One night we were out camping and there were headlights appearing in the distance like Wolf Creek, coming closer and closer, then they would just disappear. Then there was like a procession of cars for an hour just out in the middle of nowhere, then they would disappear, too. I was like, “What is this, a cult like coming to meet in this weird place? Where are they going?” That made it hard to fall asleep. I did find out in the morning that the headlights were disappearing because they were turning behind the hill into a campground, but that was still creepy. One night, Ang made me crawl in her tent at like three in the morning with either a knife or an ax from the movie because she was scared. Just camping in the dark out alone is scary!

Filmmaker: I totally agree. I’ve never really been camping before—I’ve never even been in the desert before—so that’s a totally alien and horrifying experience to me.

Banfitch: I have more fear in forests due to a fear of bears, even though it’s absurd when you look at statistics. In the Mojave, you don’t really have to worry about big predatory animals. You have to worry about small predatory animals that actually kill you a lot more than bears. But because they’re small, I’m not scared of them. Which makes total sense.

Filmmaker: I also wonder if the conditions of the desert itself ever presented you with any challenges?

Banfitch: Wind was the biggest challenge, just for the purpose of recording dialogue. It was very hot a lot of the time, but Ang and I know how to rock out, pour water on ourselves, smoke stogies and pretend that we’re in the Caribbean, so the heat wasn’t really a big problem. Also, I’m naked for a lot of the movie, so I wasn’t wearing warm clothing. Nighttime in the desert is pretty cold, especially naked and covered in blood, so that was not comfortable for Ang or I.

Filmmaker: Were there any desert-specific cold cases or folklore that inspired you in the process of crafting The Outwaters? Particularly because the Mojave is named for the Indigenous people who live there, I wonder if any Indigenous mythology wormed its way into the film. Also, deserts are notoriously reliable dumping grounds for bodies—the remains of those who are buried there are often never found.

Banfitch: You know, not that I can think of. It was all planned out due to the logic that these characters live in LA, and where would they go to try and get a cool shot? Although I did certainly think about the Indigenous land aspect, I thought [that these characters] might not necessarily talk about that on camera. So I knew that [idea] would be present, but didn’t feel like I should have them talk about and make a point of it. It didn’t feel as realistic.

Filmmaker: No, they don’t seem the type to be meditating on Indigenous practices on camera. But I’m curious, what were some touchstones for the cosmic horror visuals of the film?

Banfitch: Terrence Malick’s work. my general appreciation and love for nature—I worked at Greenpeace while making this. Nature can be, obviously, completely beautiful and completely terrifying.

Conceptually, the title came first. One of my favorite words is “outland.” I think it’s a beautifully evocative word, then I thought, “Well, ‘outwaters’ would also be beautifully evocative.” Then visuals would start to come based on the word. I explored the plot and the movie through that initial exploration of what the word “outwaters” could mean. It was all, I would say, instinctual and not very intellectual in terms of writing.

Filmmaker: Tell me about how you achieved the film’s practical effects. I’m not necessarily squeamish, but I literally gagged during the final few minutes of this film because the gore was so nauseatingly effective. I’m assuming you had a shoe-string budget, so I’m wondering how you rendered such…let’s say anatomically accurate appendages.

Banfitch: Most of the practical effects were made just using logic to think, “How could I make something?” Certain effects I had to look up on YouTube, like the intestines. Another part I ordered and was already made, then I added stuff to it to make it look more realistic. It’s pretty simple: if you make something for a horror movie and it doesn’t look real, you just have to make it again. None of it was expensive, you just have to keep working on it until it feels right and looks right on camera.

Filmmaker: It’s so interesting, because I feel like so much of the film’s bloodshed up until the very end takes place in the dark and in these really fractured images. But [SPOILER ALERT] the filmmaker’s demise is in stark, broad daylight. I’m also curious about—and it’s so hard to describe, because you’re not even really sure what you’re seeing when you’re watching the film sometimes—that cosmic dreamscape that your character finds himself in where he’s confronting this beast or entity. How did you achieve that? It’s black and pulsating and just really fragmented.

Banfitch: I made that from different elements that I ordered online. I always knew it was going to be shot in the dark with a flashlight, but had I shone the light on the whole thing, it still would’ve looked real. I have a tip: Everything looks better if you throw some dirt and blood on it. And sand! It adds to the texture. I definitely muddied everything up.

Filmmaker: The film’s original music and score add a sublime narrative layer, and I know that many different parties contributed on this front. Salem Belladonna composed the score, but you also contributed music as a singer-songwriter. Obviously, Michelle May’s vocals and her character being a musician were also integral to the film. I also listened to the Spotify playlists you made for each character, which were wonderfully eclectic but aided in fleshing out their distinct personalities. Can you speak broadly to how music shaped and influenced the project?

Banfitch: It’s not an exciting answer, but a lot of it was just practical since it’s a found footage film. I played the kind of music that I would be listening to or that my friends would be listening to in the background when we’re hanging out. The two pieces that Salem created for the movie—I needed a pop dance song and this completely brilliant, beautiful choir piece—were really just based on, “What would the characters be listening to?” And on the practical side, I didn’t have any money and I was cheap, so I could just give my own songs to the movie. [laughs] Tim Eriksen did a lot of the music for Cold Mountain, and he’s been a favorite artist of mine since high school. I reached out to him and told him about the project and that I didn’t have any money, but I loved his music and really wanted to get a couple of his songs in there. He was gracious enough to let me go through his catalog and pick a couple songs.

Filmmaker: Also, the footage of the “wild” burros is absolutely exquisite, and I know they do in fact reside in the Mojave. How did you coordinate shooting them?

Banfitch: They’re CGI.

Filmmaker: Huh?

Banfitch: Just kidding! We can all thank Scott, my co-star/friend, because they were just there and I was in a bad mood and didn’t feel like filming them. And he was like, “You have to get out of the car and film them!” So thank you, Scott. It’s hard for me to start recording. I have issues with getting going. But once I’m recording, I will just get totally lost in shooting, so I was able to get plentiful shots of the burros. I am also used to shooting animals in nature for my other films. I would camp out in the woods and wait until deer came.

Filmmaker: That’s really wonderful happenstance, because I think that they add such a complex contrast to the lone travelers in the desert that you and your friends play. Like you said, most animals in the Mojave are rather small, and the burros are these big anomalies—almost outsiders, like your characters are.

Banfitch: I can’t imagine the movie without those wild donkeys. I can’t believe not wanting to film them because I was grumpy. What an idiot. [laughs]

Filmmaker: Finally, I know you have two features mostly completed right now. Would you like to share more about the films and when we might expect them?

Banfitch: Tinsman Road is a feature that I shot while editing The Outwaters, and that’s going to premiere at a festival in San Francisco in March. It is a mystery-horror-drama, and it’s nothing like The Outwaters. It is also found footage. I actually shot that on MiniDV 4:3.

Filmmaker: Oh, cool.

Banfitch: Yeah, it was really exciting. I did forget that tapes can be eaten—I’m not used to that. There was no crew, just me with my laptop from 10 years ago that was about to blow up, which still has FireWire on it. I was like, “Oh my God. All of my movie is on these tapes, and I have to get the tapes onto this laptop and then hope the laptop doesn’t blow up.”

My first feature, which I filmed before The Outwaters, is called Exvallis. It’s kind of another word I made up, but it’s a black and white, silent art house drama. That’s not found footage and has very classically composed shots, and I still need a composer for that. I don’t have any money, but that film is done aside from needing an original score, so that’ll probably be the last of the three to be released.

Filmmaker: Did you also act as DP and editor on those films?

Banfitch: Yes.

Filmmaker: Is that something you think you’re going to continue, or is it mostly a circumstance of financing?

Banfitch: Well, I love editing. It’s my favorite part of the process. I can’t imagine not editing. Although I would love to work with different editors for new ideas, I love editing. I love shooting as well, but I’m not as technically apt in it. I hope to be working with my best friend from college, Robert Carnevale, on my future projects because he’s wonderful. We used to go to college at SVA together, so he shot my thesis film White Light, which is available online if you get bored. It was shot on 16mm.

Filmmaker: I also have to ask, and I wasn’t really sure how to craft this as a formal question: watching The Outwaters, there appear to be several loose allusions to the queer experience. Especially the final scene wherein your character ultimately perishes and unravels, I think it hit very hard in terms of destroying or “debasing” the body.

Banfitch: What I would say is that it was just a human thing for me, when it comes to the destruction of the human body. That said, I was aware that people could find layers in one particular moment. [laughs] But everything came from instinct and was not necessarily about me thinking about symbolism in any way. If there was anything stemming from me growing up as a closeted gay person through my early formative years, I’m not aware of it specifically. But the prequel short film, Card Zero, is very gay. It’s a memory card that was found at my [character’s] apartment before we go out to the desert. It focuses on my cringey relationship antics, but it has an omen of doom hanging over it, obviously. Then there’s an epilogue composed of restored footage. I’ll send them to you—the total runtime is about 50 minutes, so you can bang ‘em out. On that note, I love your Gummo hat.

Filmmaker: Hah, thanks. I’m a huge Gummo fan. I was the kid in college who tortured all of my friends by making them watch it with me.

Banfitch: I showed it at a high school party. Actually, that’s where I met Lauren Jacquish, who sings the song over the end credits in The Outwaters.

Filmmaker: Yeah, as a Jersey girl growing up in what felt like a cultural wasteland, I was just trying to rebel against the suburban in any way possible. I guess Gummo was the edgiest thing I could think of being into. [laughs]

Banfitch: It’s such an inspiration. I was getting very overwhelmed, worrying about who I want to be as a filmmaker. Then I saw Gummo—I mean, I’ve seen it a million times, but I haven’t seen it in a while—at the theater a couple weeks ago in the midst of my anxiety about all of this. I was just like, “Oh, I can just do whatever I want in terms of trying to be an artist.” So that film really did help me out years down the line!