Back to selection

Back to selection

“A Call to Action for Everybody To Preserve Their History Before It’s Gone”: Kristen Lovell and Zackary Drucker on The Stroll

The Stroll

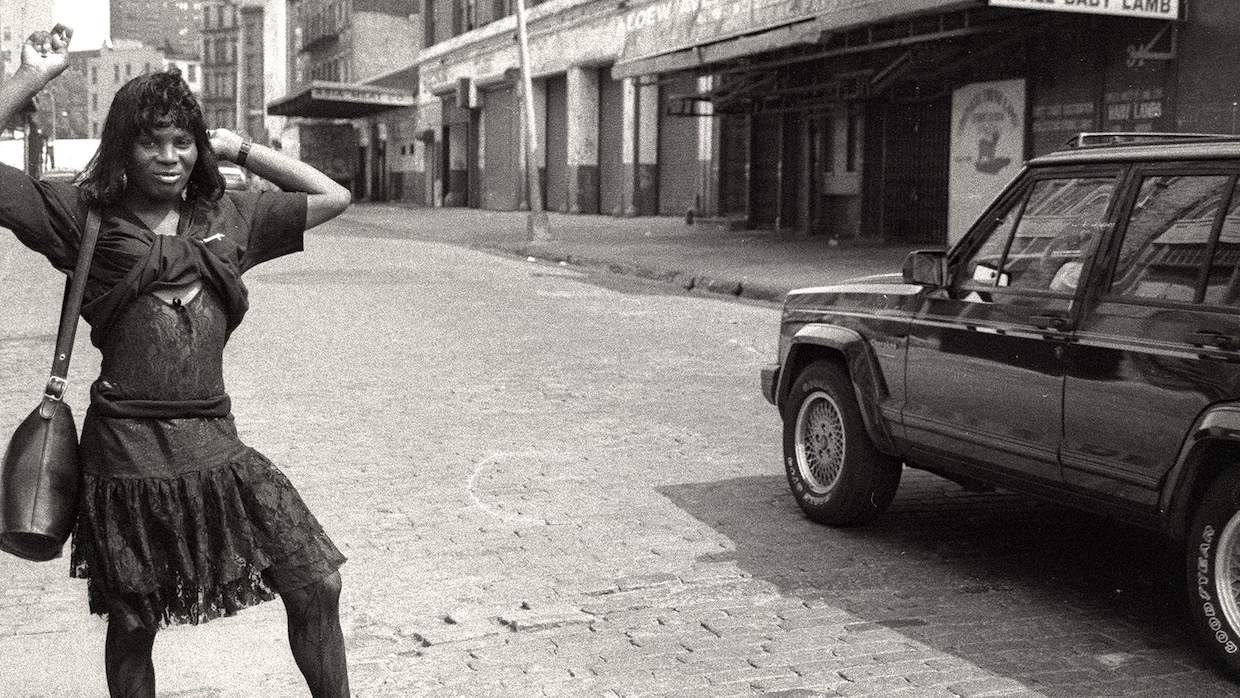

The Stroll Kristen Lovell and Zackary Drucker’s Sundance-premiering The Stroll is a beautifully and lovingly crafted time capsule of NYC’s Meatpacking District that mostly spans from Giuliani’s infamous “broken windows” reign of terror through Bloomberg’s post-9/11 “gentrification on steroids,” as one knowledgeable interviewee ruefully reflects (seconds after I coincidentally yelled those same words at my screener). Unsurprisingly, our billionaire mayor did indeed view unrestrained capitalism as the solution to every problem, including that of the “undesirable” communities—starving artists and sex workers—that called the neighborhood home.

For me, the most revelatory aspect of this heartfelt walk down memory lane isn’t that it’s offered from the POV of the mostly Black trans sex workers (including director Lovell) who made their money working the area nicknamed “The Stroll,” but that the filmmakers were able to track down so many that both survived and thrived (at least a dozen, with some whose time went all the way back to the early ’80s, remarkably enough). Clear-eyed and unapologetic, this band of sisters somehow managed to avoid the fate of famous activist contemporaries like Marsha P. Johnson (whose body was found floating in the Hudson River in ‘92) and Sylvia Rivera (who died of complications from liver cancer in 2002 at age 51).

Just prior to the film’s June 21 release on HBO, Filmmaker reached out to the co-directors to learn all about the process of using cinema to set the record on queer sex work history straight.

Filmmaker: I read in the press notes that you initially got connected through the film’s producer Matt Wolf, and that Zackary was “immediately eager to join Kristen in her mission: to tell the story of trans women surviving and creating sisterhood in the streets of New York City,” which made me wonder what specific role each of you played in crafting the doc. Did Kristen handle tracking down the characters and archival material, while Zackary shaped the aesthetic? Did you both conduct interviews? How exactly did you divide up directing duties?

Lovell and Drucker: The three of us worked together as a creative team and the roles and responsibilities were fluid, but we were a unit—drawing off each other’s experiences with a foundation informed by Kristen’s own life experience and the longterm relationships with our subjects.

We pre-interviewed folks and also drafted questions together. Kristen interviewed our main subjects on camera, and Zackary interviewed our secondary characters. While interviewing, we were all on a live Google document on an iPad so we could “mind meld” while interviews were conducted.

The creation of this film was a massive undertaking with a small core nucleus of five people, including our editor Mel Mel Sukekawa-Mooring, archival producer Olivia Streisand, and our associate editor Johanna Cameron. We were in the trenches every day on Zoom for many months, crafting this as a bicoastal team.

Filmmaker: I last interviewed Zackary about her HBO docu-series The Lady and the Dale, another co-directed project, this time with Nick Cammilleri. Awesome + Modest, which uses hand drawn and mixed media techniques, created the animation for that series as well. So why did you choose to work with animation, and even the same company, again for this very different film?

Drucker: There’s a lot of heaviness in these stories, but also a lot of joy. We sought a groundbreaking way to forefront levity and humor in parts of the storytelling that lent themselves naturally to it. Our animation strategy was unlocked by our subjects talking about transforming into superheroes as a means of survival. What better way to bring that shared metaphor to life than to literally transform the girls into superheroes?

I have a longterm and deep collaboration with Awesome + Modest. For this film I was inspired by our archival imagery, and Kristen and I loved the grimy, tactile, zine-like animation A+M conceived. We cast trans models from the community to help bring our cast’s stories to life. Animation is often very literal in docs, and A+M really enhances the cinematic language in ways that are exciting to include in stories that are grounded in reality.

Filmmaker: Watching the doc was also really a walk down memory lane for me. I really appreciated the fact that though the film centers on the women and their stories, it likewise includes interviews with a gallery owner and even a meatpacker. Trans sex workers weren’t separate or “marginalized” in that space—they were just a normal part of an entire downtown ecosystem, the fabric of a nighttime society. So did you always plan to develop The Stroll itself as another character?

Lovell: The Stroll means so many things to different people. It’s a site of joy, trauma, self-discovery, loss—and it’s gone as a place. A lot of times documentaries have to bring to life people or places that are no longer with us. So in that respect, yes, the film was very much about bringing to life the character of The Stroll.

Filmmaker: I also truly appreciated your nuanced depiction of the queer community. You include that famous clip, which always brings me to tears, of the fearless Sylvia Rivera onstage calling out her fellow gay and lesbian activists for their shortsighted (what I consider a heteronormative cisgender supremacist) vision, one that throws the most marginalized under the bus. And you even do a sort of “calling out” of your own for RuPaul’s tone deaf attempt at humor at the expense of sex workers in another clip. So what were the discussions like about how to approach that noninclusive “third rail”?

Lovell and Drucker: Most folks who lived in New York in the 1980s, ‘90s, aughts, have a story or anecdote about encountering or witnessing trans women in the Meatpacking District. And after seeing our film, many of those viewers have had a moment of reckoning; it’s been one of the most frequent types of feedback we’ve gotten. This is not just the story of a neighborhood or a community—it is a story about the history of New York City. And even bigger picture, it’s about advanced capitalism, gentrification, white supremacy, and policing in America. Everybody is a part of this story. RuPaul included.

Filmmaker: So what do you (and your characters) hope audiences will ultimately take away from the film?

Lovell: I have lived experiences that parallel so many of our subjects. It’s a unique position to be in as an author of the story, but also in some respects, one of its subjects. I was at the helm of telling the story with my collaborators, and I’m so grateful for their trust. Many saw the film for the first time at our premiere at Sundance and recently in the center of the Meatpacking District, which was a powerful experience for all.

This isn’t a film about me, it’s about a shared experience, but of course history is always subjective. This in many ways is my take on a history I was a part of, but it’s also a call to action for everybody to preserve their history before it’s gone. I hope this is one of many more stories that will be told about the Meatpacking District, about trans life in New York City, and about our resilience across time.