Back to selection

Back to selection

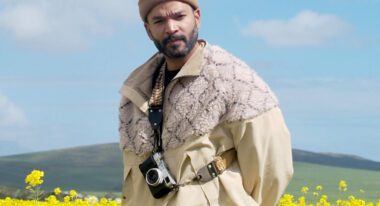

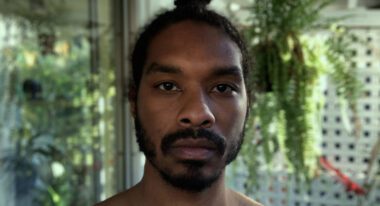

Reject Departmental Sectarianism: Production Designer Akin McKenzie and Writer-Director Terence Nance

Random Acts of Flyness

Random Acts of Flyness Ahead of the first-ever International Production Design Week, the Production Designers Collective has coordinated a series of interviews with directors and production designers, in which they discuss their working dynamics and mutual passion for the craft of storytelling.

At the heart of production designer Akin McKenzie and writer-director Terence Nance’s long-running collaboration is a mutual recognition of the importance of, as Nance puts it, “creative execution that flows from emotional framework.”

The two first worked together on the Peabody-award-winning HBO show Random Acts of Flyness and went on to create Space Jam: A New Legacy and award-winning commercial campaigns for TELFAR, Calvin Klein and others.

When we sat down to talk, McKenzie remembered the challenge at the start of their creative relationship on Random Acts of Flyness: “Part of the task was interpreting really beautiful but, in many instances, very abstract ideas that needed to be grounded and created physically. So, the conversation became: how are we going to realize this when we have five dollars?”

Nance interrupted to correct the record: “Four dollars.”

Below, they discuss making the abstract physical, the feelings behind material objects that become set dressing and the need to retitle the role of production designer to McKenzie’s preferred credit, director of design.

Filmmaker: Can you tell us a little about your creative process together and how the way you collaborate might have changed between projects as varied as Random Acts of Flyness and Space Jam: A New Legacy?

Nance: Because there was no space between Random Acts of Flyness season one and Space Jam, from the years 2017 all the way through 2019 we never lost contact. We were always in a dialogue. Maybe it wasn’t as traditional as, you have time to present the scripts and formulate questions. It was much faster and more about intuition. A big part was Akin’s instincts around what he was feeling, and a lot of that is always in conversation with resources, especially on Random Acts. The cookout in episode four is an example. You know, the original idea was to shoot a cookout. Like, let’s go outside. But it was the winter in New York, so we can’t shoot a cookout outside. Then it was like, well then, how can we build it? The idea of making it obviously a set, kind of Sesame Street-esque, saturated in innocence vibe, came into play. Then it became Akin pitching German expressionist versions.

McKenzie: Some of the more creative stuff we did on Random Acts was because the writers had written a bunch of avante-garde things that were so emotional and profound that if you read them initially, you’d think they would have to have a lot of money attached to do them justice visually. I would take that feeling and translate it into, “How can we use creative energy to fill in for the things we don’t have?” So sometimes we’re signifying those worlds and embracing the fact that they aren’t going to be photorealistic, that they will be stylized, and that we’ll use that as a metaphor too. That cookout is a great example. At some point in the spitballing that was gonna be a popup book, and if we had just a little bit more money, we’d come out and see hills of 2D houses that would tip over like dominoes and slowly crash in all directions.

Nance: You’re reminding me that a lot of what we are trying to interrogate is creative execution that flows from the emotional framework. That segment was about how Black people have been colonized into practicing the American nuclear family, a house of cards that is fragile, candy colored, aspirational, but ultimately vacuous and vapid and it’s falling down for everybody. That is what the popup book ends up meaning. But we don’t talk like that when we try to make it. Akin brings a level of understanding of what is coming through emotionally and how to actually bring that out into the world.

McKenzie: This is just a metaphor, but I feel like in some instances people want to talk to you about a couch. A director is talking about a couch, and you could spend all your time talking about this couch, then searching around blindly for some couch. And if you’re just talking about the couch, then I think you’re failing, because you should be talking about the story of what the couch represents. Why are you talking to me about this orange couch? Is it because when you were a kid, your mother had an orange couch and that made you feel a type of way? Well, talk to me about your feelings, because if we want to apply these feelings of your life to this new child’s life, which is hearkening back to things you’ve experienced but also has its own unique experiences, then I’ll find the tone and tenor to be able to find a swath of couches and then come back to you and reintroduce you to a couch that speaks to your memory, but is also more specific to the character of the film. That is what Terence and I sit and spend our time discussing. Then we get to go out from that deep understanding and apply physical elements to represent those feelings. That is how I feel most inspired as a creative.

A quick note about going from Random Acts to Space Jam: I ended up quitting Space Jam because the vision I was attached to, which was Terence’s vision, was no longer the driving force of the film. Which is a long story in and of itself. But at that point I chose to leave. So, we went from Random Acts of Flyness—where we have the freedom to create, and to be artists and thinkers and questioners of the world around us, but without the resources—into a space where you have all the resources you can imagine and none of that freedom. And it didn’t really work.

Filmmaker: Thinking about production design overall, is there anything you both are drawn to or notice when you’re watching other films or shows? What makes for good production design and how do those ideas influence your own collaborations?

Mckenzie: That’s an interesting question, because sometimes catching your eye is the least appropriate thing for production design to do. But for me the root is the beautiful films that I watched in film school that I was inspired by how perfect the world-building was in their production design. Adventures of Baron Munchausen and those kind of wild, epic creative things which transport you as a child into a world which doesn’t exist, but allows you the freedom to dream. Some of the stuff you see both in Terence and I’s work is like that balance of big creativity, big beautiful thoughts and very real societal issues and conversation with the ancestors and spiritual connection.

Nance: That question invites me to think about how difficult it is to course-correct our understanding of what cinema is, and what the process can be apart from the departmental sectarianism that became typical when it became industrialized in the studio system. It then translates to how we as people who make films are expected to watch [them]—separate the photography from the acting from the production design, and even within production design, separate the set decoration from the props, etc. There’s these sort of fractal layers of separation that, if it’s noticeable, doesn’t work for the film. The spell has been broken if you can even see those seams. I see a respect between the person photographing it, the costume designer and the designer, as opposed to a flourish. I see three to five people dancing together in a way that finds moments of breaking down that sectarianism.

Filmmaker: Is there anything else you’d like to say about the designer/director collaborative relationship? Or any goals for continuing the conversation around that relationship?

Nance: Something that Akin put me onto is the necessity of and the effort to understand “production designers” as “directors of design.” “Directors of design” for all the ways that the film is designed in the same way that “director of photography” is used for all the ways that the film is photographed.

McKenzie: When I was doing Q&As after my last film, a lot people needed to be reintroduced to what it is that a production designer does. The term “production design” is not super user friendly if you’re outside of the industry, and even some people in the industry, I’m sure, are unclear about what the combination of those words mean. So, I would say, “Well, there’s a director, then there’s the director of photography who”—as Terence put it—”directs all of the visual stuff that we’re capturing through the vision of that director. And then there’s the director of design, who does the same type of world building that you’d imagine the director of photography doing with light, but with physical elements.” Then everybody in that audience would have this aha moment of “Oh, that’s what those words are that we hear and don’t understand.”

Nance: Kids would want to do it. Once you name it “director of design,” it becomes available in a kid’s imagination that they can express themselves as opposed to be only beholden to a production. It’s like, “Oh, I’m the director of something.” I think that’s a huge spell that needs to be cast among people, because so much of how you experience a film is how it’s designed, and a lot of artists don’t even know that’s a place one could express themselves.