Back to selection

Back to selection

“Maybe an Individual is Only as Interesting as the Energy Surrounding Them”: Angelo Madsen on His True/False-debuting A Body to Live In

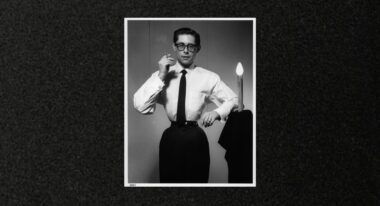

From A Body to Live In

From A Body to Live In Angelo Madsen’s A Body to Live In is a doc as unconventional in form as its leading man. Comprised of various formats (16mm, VHS, archival, 2K) overlaid with underground voices (Annie Sprinkle and Ron Athey are probably the best known), the film takes us on a winding journey through the life and philosophy of photographer-performance artist-ritualist Fakir Musafar, one of the founders of the modern primitive movement. With the archival Musafar (born Roland Loomis in 1930) as our guide we’re introduced to an unheralded slice of LGBTQ+ history that includes gay BDSM parties, the first piercing shop, body modification as a balm during the AIDS epidemic, and of course body-based performance art. And this is all while never really getting to know the queer Korean War vet, whose anthropological fascinations led to dabbling in flesh hook suspension by the mid-’60s. (Musafar eventually married BDSM educator and ritualist Cléo Dubois, who remained by his side till his death in 2018.) But this elusive quality is as it should be when it comes to celebrating a mysterious artist for whom seeking, not answers, was the point.

A week prior to the doc’s February 27th True/False debut, Filmmaker caught up with the director and interdisciplinary artist to learn all about A Body to Live In and making art from life.

Filmmaker: You met Fakir in 2004 and remained friends until his death in 2018, but at what point did you know you wanted to make a film about him? How long had this doc been in the works?

Madsen: Fakir came to see one of my films screen in San Francisco in 2017. Kairos Dirt & the Errant Vacuum was a community-made, campy narrative feature about an intergenerational interdimensional romance, thinking of the entrances and exits of the body as portals to other worlds. He had a deep appreciation for the film, and we talked about how the story resonated with his life’s work.

By that point he had his cancer diagnosis and knew his time was limited, but that’s when I started thinking about some kind of project involving his work. Then in 2019 an old mutual friend of ours encouraged me to do something with the archive. Cleo, Fakirs’ widow/ co-conspirator in all of his projects, and I began talking more seriously. She was still deeply in grief so it was a slow process to start.

By early 2020 I had made a little promo reel for funding, but then everything got sidetracked with the pandemic. Work picked back up on the film in 2022, and by then I had had an extensive amount of time to sit with the enormous archives.

Filmmaker: The last time I interviewed you, for North By Current’s Tribeca premiere back in 2021, you spoke about working from the concept of “Queer refusal,” and specifically “how certain parts of a story are sacred and not for everyone’s consumption.” I feel like this might apply to your latest as well since A Body to Live In is about a legend in the body modification subculture who purposely remains elusive to us. So how did you decide what to show and what to keep offscreen?

Madsen: Man, such a good question! This film was a real challenge. I think in part because some of the big picture questions that I initially wanted to tackle, like generational reconciliation and transformation over time, were simply not in the archive. I would have had to generate content differently to explore some of those lines of inquiry.

I think at the end of the day I wanted to stay rooted in the archive and the history more than I wanted to bring in my own questions, even though I do a bit. Viewers should be left with a lot to ponder. How do we ever really know someone? In almost all of Fakir’s archival interviews his answers to questions are the same, sometimes word for word. It’s as if he had a script – which he kind of did. He keeps it very direct, very brief, and no one really asks, “What do you mean by that?” or “How do you define that?” or “What problems do you see with x, y, z?” And of course it’s not only that interviewers aren’t digging, it’s that the concerns and interests of those eras were just completely different. The questioning is in line with the concerns of that moment in time when the questions are being asked. I longed for something more conversational or confessional, but he never let his guard down in an interview.

The film is biographical, but it barely scratches the surface of this life experiences. I wanted to create an experience that felt in conversation with his framework and belief structure more than I wanted to illustrate his life story — that’s a better job for a book project. And I wanted to position it within a specific history and community and subculture. And I barely scratch the surface of those because there is simply too much.

Yet at the same time, there was too little of precisely what I was looking for. I was ravenous for some semblance of self-doubt, a murkier kind of internal reflection. But it simply wasn’t there – on tape. So all I can do is point toward these gaps, or talk around them. Or in the Trinh T. Min-ha sense, “speak nearby” them.

I also chose to only go into his personal life when it was intersecting with the framework, the culture, and the community because those were my core interests. Maybe an individual is only as interesting as the energy surrounding them.

Filmmaker: Could you talk a bit about the film’s aesthetics? The combination of several formats (16mm, VHS, 2K) with the 100-plus hours of unseen footage from Fakir’s archive is quite visually arresting.

Madsen: I wanted to bring his photographs to life, but at the same time keep the material feeling intact on its own. A still image should stay on the screen long enough for someone to experience its full presence as an artwork. I didn’t want his photographs to feel simply illustrative. And I want them to be understood as photographs. As artworks with their own parameters of experience, not just some visual content for the film. They should be generative or conversational or discursive.

So I really leaned in to all of the photographs. All of the sequences of “animation” (though admittedly I’m kind of allergic to animation) are created from fragments of darkroom processed photographs from his collection that are magnified sometimes 100x. So that grain from the processing is very visible.

In some ways that kind of approach was in line with my goal to use as much of the archive as possible. Even though there are thousands of images you don’t see in full, you see many in partial as part of these stop-motion grain sequences. Then there are his original 16mm and 8mm films, almost all of which are lost, which is the saddest thing in the world for a film nerd. Most of what I was able to gather from those reels was converted long ago and is very low res.

With the present-day 16mm portraits that we shot of the elders, the intention was to create a feeling of connection between the archival and the present-day images. I didn’t want on-camera interviews because I wanted to really just focus on voice and divert gaze from appearance, but I still wanted visual representation of some kind. So the 16mm motion portraits were a great way to do that.

I also wanted these object tableaus, which appear as more contemporary footage – where we get to imagine use, instead of it being demonstrated. I like this idea of the time being slippery, some uncertainty as to where in time images are being positioned: Are we in a historical moment? Are we in a moment of contemporary reflection on a historical moment? The film weaves between those.

Filmmaker: Annie Sprinkle and Ron Athey are among the notable “queer elders” familiar with both Fakir himself and the body modification movement (and its intersection with BDSM). So how did you choose who to include to allow the film to unfold “conversationally”?

Madsen: Essentially I reached out to people that appeared in the archives. Keeping with that goal, of keeping the work rooted in the archive, I wanted to speak with those whose visual image was already part of Fakir’s history. That was the guiding principle.

There were a few other folks who are well-known artists who appeared in the archive that I wanted so badly to include in the film. But they just weren’t interested, which is fair. However, I think some other voices could have really shaped the content differently; the challenge of an edit is to work with what you have. But there are also several amazing interviews I did that didn’t make it into the final cut. Just too much information to put in one project.

Filmmaker: While many filmmakers develop personal relationships with their characters, your films tend to grow out of already established relationships with both characters and subjects. So what are the pros and cons/challenges of collaborating with “family”?

Madsen: This is actually something I’m thinking a lot about right now. The pros of working with fam are that you can be messy, dumb, inefficient, floundering and not worry about being judged for your lack of professionalism, whatever that is. The cons are that all of your personal baggage is out in the air. But maybe that’s a pro? I don’t know. A former collaborator told me I should stop working this way because it wasn’t good for my personal relationships. And a recent mentor suggested that the reason I work with friends is because I’m too scared to be vulnerable with “professionals.” It’s all just information that I’m sitting with.

I enjoy working with things I’m already close to because I feel like my own insight into the experience is keenly specific to the material. I feel more well-equipped to “speak nearby.” I’ve also just had many different kinds of experiences in my life, and have always been curious about ways of being and doing, so I already have a lot to draw on in my work. And at the end of the day, I’m coming at it from a place of affect. I’m not exactly a researcher, though I do research. I’m not a storyteller, though there is some story. I don’t know. I want to generate an experience, a communion of sorts, and I just use the tools that I know how to use to do that. In some ways it’s a path of least resistance.