Back to selection

Back to selection

Poetry in Motion

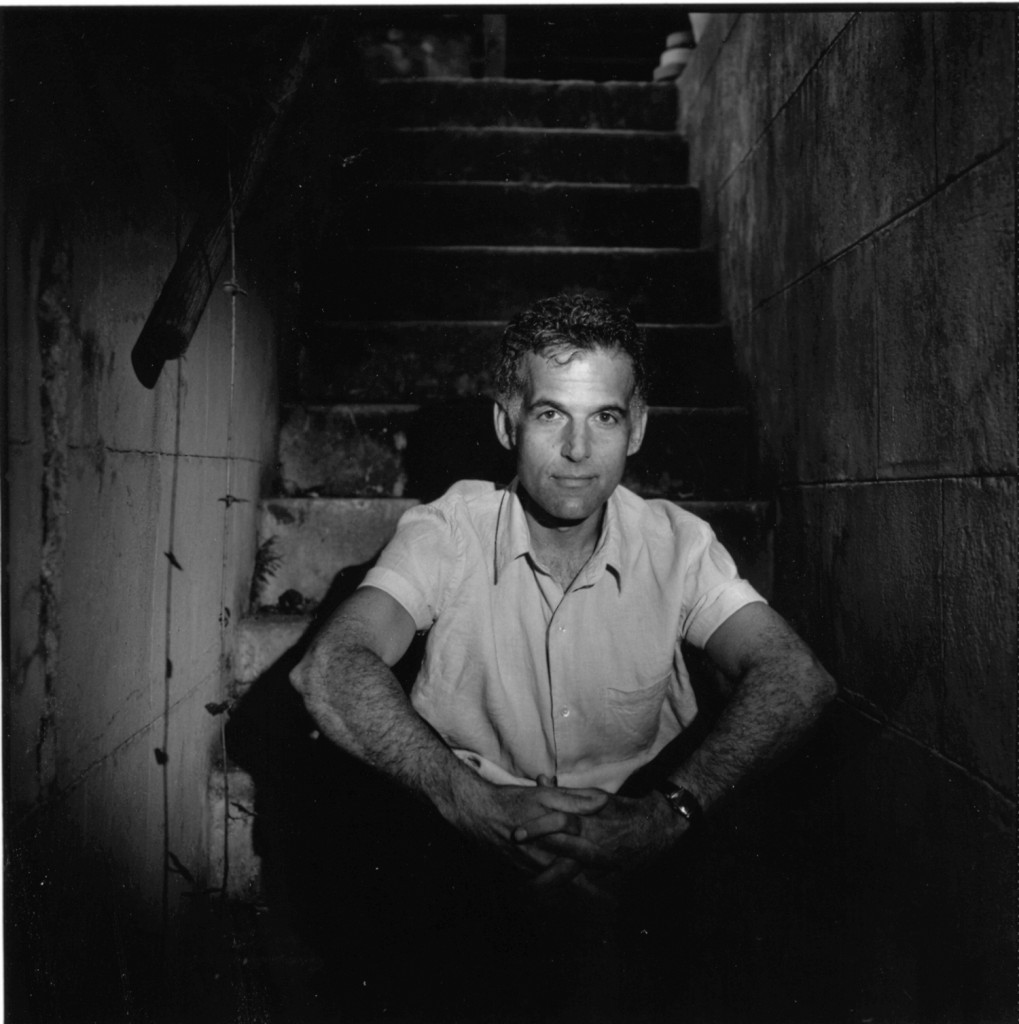

Since his 1990 breakthrough Short of Breath, San Francisco-based filmmaker Jay Rosenblatt has honed a particular film aesthetic, a form more related to poetry and essays than traditional film narrative. Combining found footage, poignant spoken narratives and targeted scores, Rosenblatt explores large social, even philosophical, issues with poetic precision. Images and spoken word do not so much illustrate as resonate against each other, suggesting a range of meanings and further associations, but never definitely naming one. The meticulousness by which he creates these short films lead Atom Egoyan to call him “an exquisite artist who makes beautifully crafted miniatures.”

In October, Rosenblatt presented a weeklong run, “The Darkness of Day: Recent Films by Jay Rosenblatt” at MoMA. Including the 2009 26-minute The Darkness of Day, the 2005 28-minute Phantom Limb, the 2006 10-minute I Just Wanted to Be Somebody, the 2006 3-minute Afraid So and the 2002 3-minute Prayer — the films reaffirm Rosenblatt’s place as one of America’s most intelligent and innovative short filmmakers and will be seen in February 2011 at his retrospective at the Walker Art Center.

We spoke with him about the retrospective and his filmmaking process in general.

You didn’t start off as a filmmaker, did you? I was actually working on a masters in counseling at the University of Oregon when I took a Super-8 class. I feel in love with it and realized that I was spending more time on that class than I was in my graduate program. Then I managed to get into a 16mm class where I was able to make three films. From there, I finally decided to apply to film school in San Francisco, and luckily I got in.

You are well known for using found footage to assemble film essays. Have you always worked in this vein? Actually my first films were traditional productions with actors and narratives. In one of my films, I needed a 1950s audience so I cut in material from a Donna Reed show. I really like the way that looked and felt, and it started to have a profound effect on how I wanted to make films.

What moved you to work completely with archival footage? In the late ’90s I was working at a psych hospital, and one evening, I came across a bunch of cans of 16mm film in a dumpster out back. I put them in my trunk but didn’t end up using them for quite awhile. I finally got them out and discovered they were training films, and that became the basis for my 1990 [film] Short of Breath. That film was wonderfully received, being chosen for New Directors, among other places. I ended up working with found footage for a number of reasons. First, I found editing was my favorite part. But the other was financial. I found it too stressful to be working with actors without a budget. So I decided that unless I had the money, I wouldn’t work that way.

Was there an aesthetic tradition for these essayistic films? Yes and no. Chris Marker, especially Sans soleil, was incredibly influential, and then there were other filmmakers like Craig Baldwin and Bruce Conner. But also I just let things happen.

The exhibition at MoMA covered work you have done since 2002. Do you feel that this new work marks a continuation or divergence from your past work? Both really. Films like Darkness of Day, which uses primarily all found footage, is very much in line with my earlier works. But Phantom Limb, which includes my family’s own home movies as well as (sort of) original documentary footage of a sheep being shorn is a new direction.

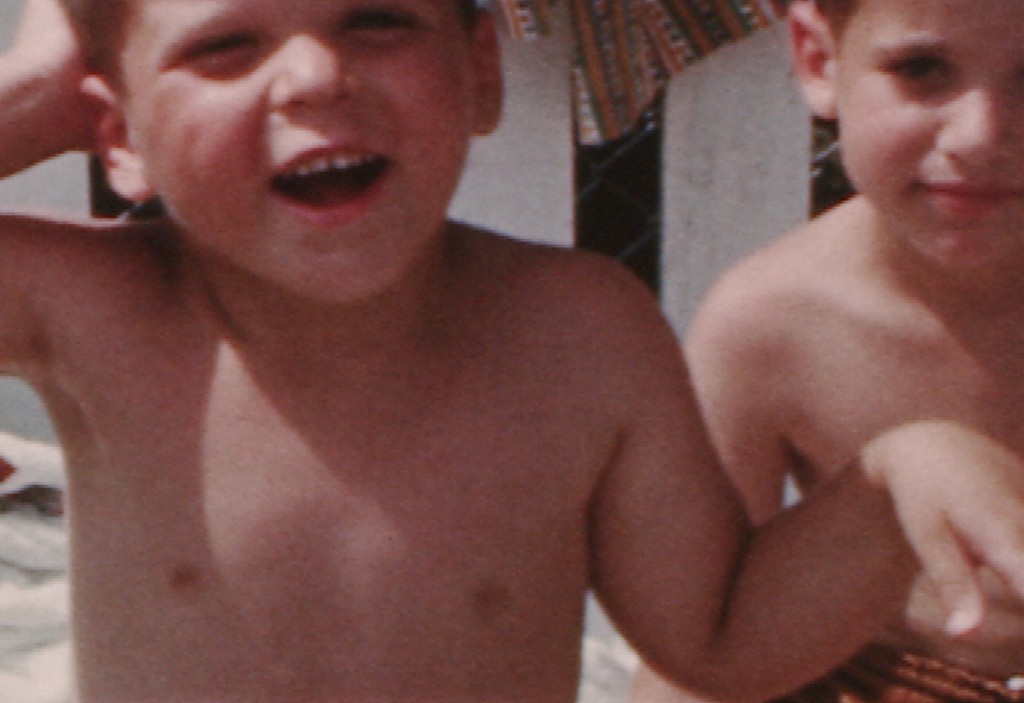

In Phantom Limb, which starts with the childhood death of your brother, the title metaphor is interestingly both literal and metaphoric. Originally I was never going to introduce the actual thing in the piece, but at a party, when I told someone what I was working on, he introduced me to someone who actually suffered from this condition. I asked him if he would be in the film and he agreed.

The sheep-shearing section, which appears over advice for grieving parents in Phantom Limb, was so poignant that it made me cry. Generally your footage is so evocative. How do you find it? There are lots of different sources — institutions that have thrown away footage, stuff in the public domain, collectors. Sometimes I use archive houses like Prelinger or Oddball Film.

As for your source material, Afraid So uses a poem read by Garrison Keillor. How did that work? Did you get him to work with you? The piece actually began with me hearing Jeanne Marie Beaumont’s poem “Afraid So” being read by Keillor on his Writer’s Almanac program on NPR. The poem is a series of questions, mostly about bad things possibly happening whose answer could be “afraid so.” I thought this could be an interesting film. I contacted the poet, who lived in New York. I think she was amazed that anyone would want to make a film from her poem. She agreed to let me use it. I’d tried different voice-overs, but I kept coming back to Garrison Keillor. Friends pointed out that I could pull his reading directly from his website. And then I contacted his people about using his voice; they said okay as long as I got permission from the poet.

Do you normally start with an idea, or a piece of footage, or some music? Each film is really different and there is never a single method. I find that everything I add creates a dialogue with the other parts. Although there are some consistent themes.

Like what? I think loss is a major theme in my work.

That seems oddly poetic, considering you work with material (film clips, industrials, etc.) that has been lost or separated from its source. On Darkness of Day, my lawyers told me to include a preface about the footage [“In the 1980s, with the advent of video, school districts began disposing of their entire film libraries. Thousands of 16mm prints ended up in garbage dumps. The following film is comprised entirely of clips from discarded films that were saved from destruction.”] They felt it strengthened my case of “fair use.” But I didn’t really want to add this preface to the film. After I put it up, it made so much sense and resonated with so many issues in the film that I am glad I did.

Watching I Just Wanted to Be Somebody, I kept thinking how odd Anita Bryant is as a subject, but she seemed very resonant, even though this film was made before Proposition 8. How did that film come about? The director of the Florida Moving Image Archives told me that he just received Anita Bryant’s home movies donated by her ex-husband. He said I could use them if I wanted to. I thought a film about Anita Bryant would be very interesting and fundable. I tried for over a year to raise the funds for a feature-length documentary to no avail. I cut a fund-raising trailer and did quite a bit of work on it. I came to the realization that I did not want to spend years fund-raising for this project but I did not want to let all the effort be in vain so I decided to just turn it into a short. I knew I wanted to have a letter to Anita read over the home movies section, and I hired a gay writer (Fenton Johnson) to write it and eventually decided to use his voice too.

What new projects do you have in the works? As far as current projects, I am just finishing a short 5-minute piece that I showed at MoMA as a sneak preview. I don’t want to advertise it by title because I want to hopefully screen it at Tribeca. Also I’m hoping that Sundance will accept it and I want it to have a 2011 copyright.