Back to selection

Back to selection

“I Was Only Trying to be Objective — That Was My Conflict:” Charles Burnett on Killer of Sheep

Killer of Sheep

Killer of Sheep With Killer of Sheep entering the Criterion Collection today in a new 4K restoration, we are reposting James Ponsoldt’s interview with its director, Charles Burnett, from our Spring, 2007 issue.

“When I stumbled across a 16mm print of Killer of Sheep at film school in North Carolina, it was like finding gold. I had never seen an American film quite like it…raw, honest simplicity that left me sitting there in an excited silence. It echoed throughout George Washington, the first film that David Gordon Green and I made together.”

— Tim Orr, cinematographer (All the Real Girls, Raising Victor Vargas)

What sort of anxiety exists in the influence of a visionary masterpiece that is virtually unknown by a majority of the mainstream audience?

According to music apocrypha, Brian Eno said, “Only about 1,000 people ever bought a Velvet Underground album, but every one of them formed a rock ‘n roll band.”

Now consider Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, shot for less than $10,000 in the Watts community of southern Los Angeles during the ’70s and considered a seminal film in the canon of independent cinema.

Have you seen it?

If the answer is no, there’s a good reason.

While radically divergent in content, Killer of Sheep is a kindred spirit to Todd Haynes’s first film, Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, and Cocksucker Blues (photographer Robert Frank’s anarchic, drug-fueled 1972 Rolling Stones tour documentary) in that it’s been legally prevented for decades from having a commercial release. But unlike those two mythically “unseen” films, Killer of Sheep has finally overcome its legal hurdles — a stellar soundtrack by luminaries like Paul Robeson, Dinah Washington, Louis Armstrong, Scott Joplin and Earth, Wind & Fire, among others, was largely uncleared — and is now, on its 30th anniversary, in theatrical release from Milestone Films with a restored 35mm print by the UCLA Film and Television Archive.

Killer of Sheep, Charles Burnett’s thesis film for UCLA, which he wrote, directed, shot, edited and produced, won prizes at the Berlin Film Festival and Sundance (then called the USA Film Festival) in the early ’80s, was labeled one of the “100 Essential Films” by the National Society of Film Critics in 2002 and declared a “national treasure” by the Library of Congress. Often referred to as an American Bicycle Thief, Burnett’s film may have more in common with the stories of James Joyce, who was famously obsessed with allowing his characters to experience “epiphanies,” which the author defined in Stephen Hero as “a sudden spiritual manifestation, whether in the vulgarity of speech or of gesture or in a memorable phase of the mind itself.”

In the opening scene of Killer of Sheep, a man lectures his son for not defending his brother in a fight. The father, only inches from the boy’s face, says, “You are not a child anymore. You soon will be a goddamn man.”

The boy’s mother, busy consoling the beaten-up and crying brother, his head in her lap, walks across the room with a serene expression on her face and, without saying a word, smacks her son across the cheek.

The boy takes it like a man.

Like a man.

This notion is at the core of Killer of Sheep: what it means to be an adult, and how children learn and internalize grown-up behavior and responsibilities through lectures, through tears, but mostly by silently observing, peeking around corners, usually unbeknownst to their parents. The children of Killer of Sheep are witnesses, sponges — loved and shielded, but not ignorant.

What do these children see?

Men like Stan (Henry Gayle Sanders) — a husband, father and worker in a slaughterhouse, where he hustles sheep to the killing floor, then cleans up the resulting mess. Stan arrives home exhausted, stressed and unable to please his wife (Kaycee Moore). When he buys a car for “fifteen dollars — and a shirt for collateral” with his friend Eugene (Eugene Cherry), believing that a new ride will prove his worth as a man and a provider, the extended vérité scene that follows, involving a steep hill, an open pickup truck and poor planning, ends hilariously. Yet the expression on Stan’s face as the motor — and with it his mechanized dreams — crashes to the concrete is one of unspeakable devastation.

Still, every morning, Stan goes to work.

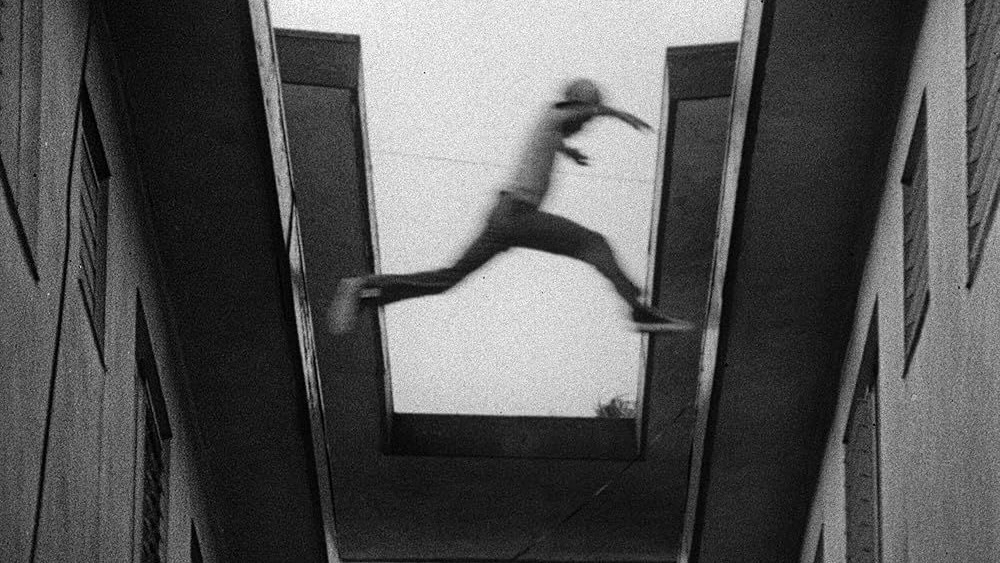

While people in the neighborhood steal television sets and disrespect their elders, and thugs plot murders, Stan returns to the slaughterhouse. While the children in the neighborhood play in empty lots, throw rocks and dirt, leap from rooftop to rooftop, learn to imitate the bathroom beauty rituals of their mothers, joyous and fearless and unaware of their own poverty, Stan mops up animal blood. What the children don’t know about their parents’ jobs can’t hurt them, and their play fights bring only crocodile tears.

But the tension created when a young daughter innocently, perhaps naïvely watches her tired father reject his wife’s sexual advances, or when children on skateboards zip into the street, unconcerned about oncoming traffic, instills a feeling of minor dread that the youth in Killer of Sheep are on the verge of discovering adulthood, with all its burdens and violence. As an audience member, you want the bliss of youth to be pure and perpetual, but of course that’s impossible. The kids must learn to be adults at some point. And like the sheep in the factory watching their kin bleed from the ceiling, unaware that they’re next, the wait can be heartbreaking.

In a scene midway through the film, an adult character lies on the floor, having just been jumped, and he’s told that he always feels sorry for himself, to which he replies, “If I don’t, nobody else will.”

Killer of Sheep doesn’t ask the viewer to feel sorry for the characters in the film, but simply to respect them, to listen to them, to recognize that they aren’t giving up, and that they deserve a dignity most films would deny them. It is a film so perfect that it seems impervious to time, as though it’s always existed, yet it is so humane, so poetically rendered, that one can’t help but utter, with astonishment and gratitude, the supreme compliment: In Killer of Sheep, the characters feel alive!

Many critics’ Best of 2006 lists were topped by a French film, Army of Shadows, by Jean-Pierre Melville, completed 37 years earlier yet never theatrically released in the U.S. until last year. Although many distributors won’t release this year’s contenders until the fall, it would be shocking if a finer film than Killer of Sheep — American or otherwise — is released in 2007. The film is currently out in limited release by Milestone Films.

So you’ve been in the studio dealing with some music issues on Killer of Sheep? I made it as a student film, and it wasn’t meant to be screened theatrically. I made the film and just put all the music in. There wasn’t an issue [then] with the rights for the music, but little did I know that today it would become an issue. Dennis Doros at Milestone had a Sisyphean situation. The people that had the rights to the song “Unforgettable” refused to grant him the rights, so that was a big delay. Finally, we decided to repeat one of the earlier Dinah Washington songs [in its place]. There’s another song — “Poet and Peasant Overture” — that we’re also going to have to replace.

Is this the first time you’ve tinkered with Killer of Sheep since initially completing it? Yeah. It’s the first time I’ve spent so much time watching it in years. It’s hard to take. It’s nostalgic, certainly. You see the community in which it was made, and it really was a community. Over the years it’s been devastated in many ways. Since we made the film, it’s become dispersed, people have moved out, crack cocaine became an issue, gang violence — in the ’80s it was very bad. It’s mellowed out a bit now, but it’s still not the same. Looking back over what you might call “an age of innocence” is tough to watch.

Rewatching Killer of Sheep, do you think your craft has changed? Would you do the same things now? I don’t think so. That was an experiment in many ways. Every time you do something it’s an experiment to some extent. You want to go further and further. It was a style suited for what I was trying to do — to get into the reality where you wouldn’t impose your values on it. To try to make it look as documentary-like as possible. I just set up the camera and caught the people doing their thing. It was very manipulative in that sense.

What were your expectations for Killer of Sheep if you made it just as a thesis for UCLA? It was a time in the ’70s when there wasn’t distribution like there is now. This was made as a demonstration to show the working class who they were. There were a lot of student films about the working class and the poor that had no connection. A lot of people were making films where they said if you do ABC, then D will happen; there will be some sort of resolution. But life just isn’t like that. [Killer of Sheep] was an attempt to make a film about the people I grew up with and their concerns. I hoped it would be shown in a context where there would be a conversation about the working class, where it could be used as a visual aid. There’s obviously no simple solutions to the problems, and that’s what I was addressing and reacting to.

You talked about how the community where you filmed has changed. Do you think Killer of Sheep functions as a time capsule? Do you think it’s —Relevant? No, I absolutely think it’s relevant. But how do you think the film relates to the world in 2007 versus the world in 1977? I think you can see the seeds of some of the future in the film. The Watts riots were in ’65, and we filmed in the early ’70s, and you can see that little was done to help the community. In a way, you look back and it’s even worse now in many ways. Then, to some degree, you could get a job doing manual labor, but now everything is so technical. Then you could at least pick up a trade from your family, who were carpenters, or plumbers, and now you have to go to school for it. In the film there’s an anti-Southern thing, like the son calling his mother “my dear,” which is like a country code-word, and she tells him not to say that. There was a rejection of certain values, but you sort of need those foundations.

Do you think you were trying to explore how rural, or Southern values, can exist within a more metropolitan environment like Los Angeles? More so in [my subsequent features] To Sleep with Anger and My Brother’s Wedding. Growing up, it was a constant clash. If you were from the South, people called you “country.” It was a negative more than a positive. But if somehow you let those [Southern] values seep in, through osmosis or whatever, you look at your life and realize [they are] relevant. You find people who don’t have those values, and it’s like they’re missing something. I feel sorry for people who didn’t come up with any value system. In the neighborhood where I grew up, the neighbors were like extended family. That’s all missing now — most of it. Los Angeles is so urban now, but it used to be full of vast, open spaces. It was rural — like Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn! You could see for miles. City Hall was the biggest building. You could see the mountains every day. You could have chickens, rabbits, ducks — anything — in your backyard. It was a great place to be at that time. It felt country. There was a sense of community. Now it’s really dirty. If you go to Africa, in some parts it’s like it’s brand-new — there you can see for miles and it’s not polluted. You go through Namibia and there are elephants on the road. There’s a sense of newness. It’s not totally exploited.

I read that you wanted to make a film during your UCLA days about the black revolution, and you told this to some older men, and they laughed at you. I find your films both incredibly human and political. Do you feel like your films are an attempt to reconcile anger, political anger, with telling gentle stories about human behavior? I didn’t want to make a revolutionary film about taking over the city or the world, necessarily. What happened was that I was thinking about how to make a film that reflected the reality of the situation. I used to get my hair cut in Watts at a particular barbershop, and there was always some conversation or argument with these older guys inside. I went in there one time, and it was Paul Robeson’s birthday or something. I was excited, but their attitude was against Robeson because they felt he’d turned against his country. They were talking about a guy who was a spokesperson for injustice all over the world! So we got into a big debate, and they were saying things like, “I’ll give you a plane ticket to Russia if you promise not to come back.” Then I realized that they’d lived through the war, they were from the South, they’d been through segregation, and yet they still had a profound patriotism and love of America. It was hard for me to reconcile. They weren’t a part of the Watts rebellion; they were responsible people who were into supporting America. They believed in the system. It made me look closely at people who were, say, economically at the lower end but who still believed politically that they had opportunities and who never thought of themselves as poor because they were working and making a living. It was an eye-opener in many ways.

At what age did you first think that you’d like to hold a camera, or perhaps make a film? I grew up watching films on an old B&W television. I always wanted to do still photography but never had a chance. This guy I knew in high school had an 8mm camera, and it was the first time I’d seen or touched one, and I [filmed] an airplane. It was a really interesting thrill. Then I forgot about it, and I was into electronics and thinking I’d be drafted. Then I discovered the student deferment program. [My] reason for going to school was to stay out of the draft. I was going to get a degree in electronics, and I started taking creative writing classes. I was also working at the library and started going to movies before my job would start. Then I decided I wanted to do cinematography and checked out schools. USC was too expensive, but UCLA said, “Come on over,” so that’s what I did. So I never made a distinction. In my mind, a filmmaker wrote, directed, edited, shot — whatever it takes to get the film done.

With all its accolades, is it hard to consider Killer of Sheep a student film? It was done as a student film — as a thesis film. So it is.

Do you think there was freedom in that? I mean, if someone else put up the money and you knew it would be theatrically released, do you think you would have done things differently? I wouldn’t have done that film any other way, because that was the whole point: doing it the way I made it, doing it anti-Hollywood. It wasn’t going to be a commercial film.

Has your writing process changed since you made Killer of Sheep? It changes all the time.

How so? Each time you look at a blank piece of paper, you wonder how you’re going to do it, starting from scratch. Your stories just take a different form. You can try to impose a structure, but that doesn’t always work. One of the criticisms I’ve received is that people will say something like, “You didn’t make another Killer of Sheep.” Folks want you to keep making the same movie over and over. But I’ve done that. There’re other issues, other interpretations. You want to do something that’s new and interesting and challenging. And each one is like starting all over again.

When I read about you, the two people whose names are often mentioned is Chekhov and Jean Renoir. I’m sure you get that a lot. No, I haven’t. Or, not enough, maybe! I think Renoir gets mentioned because I refer to him a lot. One of the first films about the South that really moved me was one of his films, The Southerner. One of the things I liked about The Southerner was the humanity and the broad spectrum of life in it. It wasn’t just about whites patronizing blacks. You saw people on an equal scale. It’s a rarity to see blacks given the same type of justice and humanity — I think that’s what attracted me to the film. In La Grande illusion you see blacks in the background while World War I was going on. You wouldn’t see that in an American film. It’s amazing that Hollywood could look at reality and then distort it out of prejudice, and it’s really painful when you see that continuing in American films. When I was coming up in school, there weren’t any positive images of black people, and that affected the children in the community who needed nurturing and support and who weren’t getting it from the institutions in this society. Denigrating black people has always been a part of Hollywood. I’ve had teachers say that blacks are too close to the subject matter to make a film about the black experience! You can imagine how ridiculous that is. You have to fight against beliefs like that. It made Renoir and other European directors even more important to me.

I heard you speak once at the University of Georgia, where they were screening some of your films, and you repeated something that one of your teachers — the British documentarian Basil Wright — once told you, which was something along the lines of “Don’t ever judge your subject.” Could you talk about that? Well, at UCLA I was at a crossroads. They had these “end of the quarter” screenings — the best of UCLA films. This was during the time of the hippie movement. And I couldn’t identify with any of them. I came from an all-black community with different conflicts and issues. And these other directors had all this freedom to explore things like nudity. There were many good films, but they were often about the internal conflict and problems of the filmmaker. I didn’t have a problem, so I couldn’t make a film like that that would relate to what I was doing. And people would smoke weed everywhere on campus — it would just come out of vents. I was always paranoid, but the campus police would walk through the hallway and ignore it all. Where I came from, police would stop you and harass you, go through your pockets — it was like apartheid. But in film school, all of these folks had a lot of luxuries and freedoms. So I was lucky to be taking Basil Wright’s documentary class at the time. He was a gentleman, very sensitive, and he made a beautiful documentary, Song of Ceylon. I felt like I had a connection with him in terms of what I was trying to do. I told him that I felt like I didn’t fit in. He told me that the most important thing is respect — for the people you work with and the subject of the film. They’re human beings, and you don’t exploit them. There’s never a justification for exploiting the subject. There was a focus on working with your subject as a living thing that’s already been hurt — you don’t need to exploit them any more. It’s not about you, thedirector; it’s about the people you’re focusing on — their needs, their interests. That’s the purpose of documentary.

Is Killer of Sheep not, to some degree, about an inner conflict for you? I was only trying to be objective — that was my conflict. Not imposing. I wanted to do something that reflected the way people in the community would see themselves. Coming from another place, you can see a much larger picture. But when you’re in a well, you can only see the narrow light above. If you’ve been living like that for a long time, it can have an unproductive effect on you in many ways. So it wasn’t my personal conflicts. It was the conflict of the community.

Do you feel that in most films you see, some individual or group is being exploited? I feel like in the majority of black films there’s exploitation. The black characters are exploited. People of color are. That’s a reason why a lot of us got into film — because there were these distorted images of black people. You see the same things: gang movies, kids who are violent, a teacher who has to straighten out the situation — usually a white teacher, who teaches [the students] how to dance, or whatever. And it’s superficial. There’s one person who’s dedicated, but I’ve seen dedicated teachers eaten up by the system. The problem is systematic, it’s systemic, it’s in the culture, it’s in the school system itself, it’s in the political system, it’s in this country. It’s inherent in this country’s policies on education. And these films don’t address this. They focus on an individual, like, “Oh, we just need one dedicated teacher, or one parent.” And that’s just one-millionth of the problem. First, we need to figure out where all the money that [was allocated to] public schools has gone, why it isn’t showing up in the classroom, in terms of books, or quality teachers, or after-school programs, or smaller classrooms. And then you take a movie like Hustle and Flow where they’re saying, “It’s hard out here for a pimp.” That’s the biggest slap in the face! I argue with people who say the main character wants to make it, he’s working hard, and you can’t knock him for that. You can’t? He pimped his girlfriend! He could’ve gotten a job at McDonald’s. And he’s supposed to be a hero? The ends justify the means? That logic justifies selling drugs, doing almost anything. And that’s what gets promoted? That’s the last thing we need in the community. Why not make something that would uplift? It doesn’t necessarily have to be overly positive, but [it should at least be] realistic and not trying to denigrate. You can’t do that with any other culture except for black culture. And that’s the thing that troubles me. Box office receipts don’t justify that. It almost seems like a conscious attempt to continue this program of dehumanization.

How do you feel when you’re labeled a “black filmmaker” or an “African-American” filmmaker? Would you prefer just to be called a filmmaker? This country is like that. It’s divided. It segregates people. When I started film school, I was just a filmmaker. Then I was grouped with African-American film, black film. It became a way of categorizing. I think it’s an indication that this country isn’t a melting pot. Even in terms of just trying to produce a script, if it’s a black story, you’re told that it won’t make money, it won’t sell in Europe.

As a filmmaker, how do you describe your work? I see myself as a person who makes films about people, their conflicts, their condition, their failures and successes, the things that resonate — things that seem simple, but have universal meaning. To share experiences — that’s what art is for. I see film as more of an art form than a commercial thing. I think because I come from a segregated experience, there’s a need to tell stories other than mainstream stories. You could say, “The stories you’re doing are about predominately black subject matter,” but they are still about the American experience.

How does it feel to have a film you’ve made be declared a “national treasure”? This is the irony of it: I went to Zimbabwe and bought a pair of shoes for something like six million dollars. And I thought, if you can buy a pair of shoes for six million dollars, you’ve arrived! Of course, inflation is such that it costs almost half that to buy a doughnut. But in terms of getting another job, it hasn’t really had an effect. In some ways, it’s made it worse. People think I’m an artist. They might not consider me for a job, like I’m not going to be part of the team. When Killer of Sheep won the Critics’ Award at the Berlin Film Festival, it was in all the European newspapers, but when I came back to the U.S., there was no press. So the “national treasure” thing is nice for my friends and me, and we enjoy it, but it has no effect on getting another film made. You just start over from a blank page. I guess it’s had its blessings. At least I haven’t gotten a big head. Honestly, I can’t complain.

What are you working on now? I’m finishing up a film shot in southwest Africa, in Namibia. It’s an epic drama. Takes place from around 1930 to about 1990, when they finally got their independence. It’s about the history of the People’s Organization and Sam Nujoma, the first president of Namibia.