Back to selection

Back to selection

A MAKER’S DOZEN: NEW DIRECTORS/NEW FILMS

Don’t be fooled: Paranoia, alienation, and irrepressible ghosts of the past are some of the common threads among the features in the 41st edition of New Directors/New Films. No one could mistake it for a series of frothy comedies or unchallenging genre fare: feel-good is hardly an operative term. What is unmistakable is that, to my mind, it remains the finest, most original film festival in New York. These mostly first and second films from around the world are edgy but accessible, fresh but polished. A combination of fiction, docs, and animation, they are not intended to soothe but rather to throw you off balance in a positive way. I’m not sure why, but this is the most impressive New Directors I have seen in my 30 years of following it. The quality is high, the films diverse, and, to be blunt, for the most part the dogs seem to have vanished.

I watched 15 features and missed 12, so my observations lack statistical validity. So I decided not to make sweeping generalizations about the choices, and force the titles into sub-categories that may help the author keep his head screwed on but are just not valid. I will review the 12 I found impressive. That leaves three additional titles that I did see but with which I could not engage, try as I might. After much thought I decided not to address them: These are new films, possibly offering something that I am not ready for. We all know how subjective our responses to cinema can be. I hope you see something in them I did not, but I do feel it only fair to name them: The Ambassador, Hemel, and An Oversimplification of Her Beauty. I hope to be proven off base.

The order of the 12 reviews is very loosely based on the strength of the film, number one being the best, for example. But this is such an exceptional group that you could scramble the titles and their ranking would still ring true. What is unquestionable is the value of New Directors. Wedged between Amerindie-centric Sundance and more commercial Tribeca, this forum for some of the finest international auteurist cinema from the past year highlights strong singular visions. Departing from tendencies at almost all festivals these days, this emphasis overrides mainstream aspirations, connections, or irrelevant promotion. New Directors offers us hope that cinema in a relatively pure form can and does still exist.

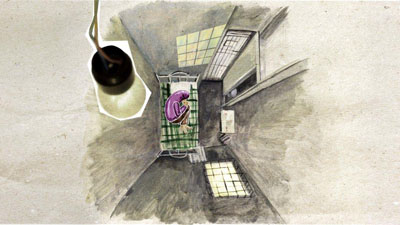

Crulic: The Path to Beyond / Anca Damian / Romania

Technically a documentary, this brilliant medley of animation and cutouts, with slivers of live action tossed in, is creative interpretation at its most sublime. Crulic has a distinctly Eastern European dry humor, manifest in the drawings and in the rapid, highly detailed voiceovers (mostly in Romanian, with a few observational points made in English).

Claudio Crulic was a Romanian who died at the age of 33 in a Polish prison after a prolonged hunger strike. The victim of a Kafkaesque bureaucratic nightmare, he was wrongly accused of theft and, once he ran out of legal options to prove his innocence, decided to call it quits. He left behind a diary, presumably Damian’s source for biographical facts.

The film begins in reverse, with Crulic’s body being transported back to his home country by his mother and sister. Then Damian begins what resembles a highly unusual two-dimensional biopic, relaying his life story, including the mundanities of the life of a petit-bourgeois man in post-Socialist Mitteleuropa who struggles to survive. For example, he imports trinkets to Romania that were much in demand because they were not Romanian-made, but goes bust when the economy falters. He is an unlucky loner: he loses his baby boy and has problems communicating with others.

What really does him in though is the injustice of the judicial system, especially in Poland. The prison officials torture him psychologically through disorientation, as if they could make his constant protests and letter writing vanish. Crulic documents his heartbreaking physical and mental deterioration. Telling a tragic true story with almost lighthearted animation techniques is a brilliant choice that pays off.

Huan Huan / Song Chuan / China

Finally, a Chinese filmmaker has combined gorgeous, if normally languorous, compositions with a relatively rapid narrative movement. Huan Huan, the young woman at the center, is an attractive peasant living in a quiet, beautiful village near a large lake. The placidity is, however, a myth: Laws like the One-Child Policy and unbearable family pressures are as stifling for her as the provincialism of the community.

The transition to capitalism has brought out the worst in people: her handsome lover, Dr. Wang, is a fraud and usurer who cheats on his wife, the latter useful to him only because she is a party official and he skates on thin ice professionally. Huan Huan’s boyfriend, Yue Lin, is a violence-prone compulsive gambler, often under arrest, who is incapable of acting appropriately enough to get any kind of commitment from her. Her pipe dream is that Dr. Wang will take her away to another town, even if it is to labor in an illegal factory–anything to get away from the village and her hounding mother.

Grandma wants her to have a baby to save face in a culture that considers it essential. Once Huan Huan becomes pregnant, probably by Dr. Wang, who wants her to abort, her mother pushes her into marriage with loser Yue Lin, sacrificing a daughter’s happiness for the sake of a grandchild.

Song adds campy inserts of a chubby second-rate female singer who lip synchs badly and is surrounded by two badly-dressed, arrhythmic young men who perform a silly dance around her. The lyrics are amazingly vulgar and explicit, a light contrast with the inflexible, soulless bureaucracy that dominates village life. These songs complement the subtlety in which Song presents Huan Huan and Dr. Wang’s lovemaking, merely with the graceful movement of tall grass in the fields, for example. The ending, especially regarding the fate of Dr. Wang and Huan Huan, is ambiguous.

Goodbye / Mohammed Rasoulof / Iran

After making such films as Iron Island and White Meadows, Goodbye is Rasoulof’s first work with a female protagonist, a disbarred lawyer-activist, Noora (Leyla Zareh), who desperately tries all avenues to gain permission to emigrate. The earlier films were well lit, open; Goodbye is anything but. (The other films are almost ensemble pieces compared to Goodbye, which retains its focus on the woman from start to finish.) Rasoulof says he was filming “not about a woman battling the system, but more about a person’s final fall without any control of the situation.” He constructed the film around its impressive sound design.

As an Iranian woman, and an activist at that, Noora relinquishes all power to men. Government agents enter her apartment at will; the judiciary is against her. Even her husband, a journalist activist who has been sent away for his transgressions, does not support her decision to take with her their child. (A slimy “fixer” had recommended pregnancy as a viable option for getting permission to leave. As if that were not bad enough, the unborn baby is diagnosed with Down’s Syndrome.)

On account of past interference with his film shoot by authorities, Rasoulof filmed Goodbye with a small camera and a minimal cast and crew (most of them unpaid). The nearly clandestine nature of the project provides a functional reason for the claustrophobic spaces and overall cold atmosphere that are formally integrated anyway with the script and mise-en-scene. Like his heroine, Rasoulof pleaded with all sorts of agencies to get necessary permits for the shoot, in order to protect his collaborators from arrest.

Neighboring Sounds / Kleber Mendonca Filho / Brazil

An urban soap opera disguised as a family drama, this film takes place around one of the sterile but expensive tower blocks of condos that pepper the skyline of Recife, Brazil, the nation’s fifth largest city, which is undergoing an economic boom. Developers are overloading the downtown with these soulless structures, which, in this film anyway, help bring out the worst in everyone living in them and their acquaintances.

Filho emphasizes sound the way most directors focus on visuals. He uses it for segues, for continuity. Seo Francisco is the wealthy patriarch who owns most of the land on his block, including the tower block where his extended family resides. He himself keeps his old, charming home, though his interests now lie in his country house and its land. The urban street is located next to a poor neighborhood, so the wealthy condo owners, racist and class-conscious, live with irrational fear.

One day some rough looking men appear on the block with an offer to sell security, vigilantes for today’s world. Everyone is a bit suspicious, but Seo Francisco welcomes them. As out of place on the street in their jackets as Hell’s Angels, their presence is the catalyst for overt hostility among the residents. The conscience of the clan, the only decent one among them, is handsome young Joao, who lacks the strength to go out on his own, since these apartments, which he makes his comfortable living selling, are a cash cow for him and his relatives.

The plot, which deviates from the usual linearity, contains wonderful twists and surprises, yet Filho has amazing control over the subject and structure of the film. As luxurious as the buildings are, they can not mask the atmosphere of dread and despair that hangs over the block. Secrets are revealed, but these vacant, spoiled people will remain as they always have been: unevolved.

Breathing / Karl Markovics / Austria

Markovics, mainly an actor (The Counterfeiters), shoots and edits in that crisp, almost symmetrical style shared by fellow Austrians Ulrich Seidl and Nicolas Geyerhofer, each of whom ventures beyond our normal expectations. Here the subject is local. A 19-year-old boy, Roman (Thomas Schubert), lives in a facility for juvenile delinquents. He was responsible for the brutal murder of another boy four years before, so his chances for parole are nonexistent. When he was a baby, his single mother had dumped him at a government children’s facility; she feared her own capacity for violence. He does not know her and has expressed no curiosity about finding her.

Unable to keep a job, a necessity for yet another upcoming parole hearing, Roman discovers his calling. He becomes a mortician’s assistant, and likes the job so much that he becomes open to some sort of transformation. The care and concern that go along with the work bring out a latent kindness, even a bit of gregariousness, in this loner. For the first time he wants to find his birth mother, and, by pure chance, he does, even if the reunion is bittersweet at best. Suddenly a lot is happening to this guy whose life has been a study in monotony. He has become an institutional creature. Schubert, a non-professional, delivers a pitch-perfect performance. He is a natural, uninhibited actor with strong facial features that make you root for him despite the horror of his past crime and his generally surly attitude.

The title comes from a recurring motif in the film. Roman dives into the facility’s swimming pool and lies on the bottom holding his breath for as long as possible. Then his mother confesses that she had attempted to smother him with a pillow before giving him up. And of course breathing is a general metaphor for freedom.

Las Acacias / Pablo Giorgelli / Argentina

A triumph of minimalism, this two-hander was shot (creatively) almost entirely inside the cab of a large truck. On account of the tiny set, this road movie depends entirely on little gestures and slight glances to advance the story of an Argentine driver, Ruben, and the indigenous Paraguayan woman, Jacinta, and her baby daughter to whom he begrudgingly provides a lift from Asuncion to Buenos Aires.

Las Acacias is as humble as it is brilliant: It refuses to announce itself as some sort of cinematic achievement. There are no recognizable urban clichés here, no scenery chewing, no stars. Giorgelli makes deceptively simple the journey from loneliness to attachment, from misanthropy and hopelessness to trust and optimism. That this is a first film by a bar owner in his mid-forties is mind-boggling.

5 Broken Cameras / Emad Burnat and Guy Davidi / Palestine, Israel, France

In 2007 radical Israeli activist Shai Carmeli-Pollak shot an insider’s documentary while participating in what were becoming weekly protests in the West Bank village of Bil’in, which had become a lightning rod for local and international anti-Occupationists and ultimately a model for such actions in other villages. Carmeli-Pollak captured both the horrors and aggression perpetrated by the Israeli military against the non-violent protesters and the mounting energy of the new movement.

5 Broken Cameras addresses the Bil’in situation, but from the point of view of Bil’in resident Emad Burnat. The problems began when the Israelis placed a section of the separation wall smack in the middle of the village, separating the residents from their livelihood, old groves of olive trees. Of course the broader issue was the government-backed ceding of Palestinian land to religious settlers.

Burnat’s access is of course broader than Carmeli-Pollak’s; after all, he is a resident, an insider. Neither a filmmaker nor an activist, Burnat got involved with this project quite by accident: He was merely filming the birth of his son Gibreel. Simultaneously, the town began exploding, so he just kept on filming. Over several years, he went through five different cameras, since all were destroyed in one way or other by soldiers.

The footage is astounding, both as a chronicle of an unjust and violent situation and as filmmaking. Burnat has an intuitive feel for the medium. Dividing the film into sections predicated on the destruction of five cameras is a clever structuring device, especially as it relates to the unfortunate fate of many of the protesters. So is the ongoing match-up of Gibreel’s childhood with the intensity of the weekly clashes. We see locals being shot, sometimes at close range, Emad’s best friend being killed, soldiers arresting little children, women being harassed, homes being entered illegally, and, perhaps most horrifying of all, fanatic religious settlers being given carte blanche to physically harm the Palestinians and burn their trees. I have seen nothing nastier than the way the soldiers treat the locals. 5 Broken Cameras should be used as evidence one day in an international tribunal.

Twilight Portrait / Angelina Nikonova / Russia

Marina (played by co-writer and co-producer, with Nikonova, Olga Dihovichnaya) is a stunning, elegant woman of means, the wife of a wealthy businessman and the daughter of a rich father. She can afford the luxury of working at a fulfilling but poorly paid job as a social worker for children.

But the new Russia is not kind to anyone, no matter if they have money or not. Corruption and crime are rampant, and sourness the norm. Soon after a thief grabs her purse from a passing car, she is raped by three policemen, including the powerful Andre. Ashamed, she tells no one of her experience, but changes in her behavior are more and more apparent, culminating in vicious verbal attacks, all based on truth, against her husband and guests at a surprise birthday party for her. At the same time, she observes clear signs of sexual abuse in a young girl she is counseling. The girl’s mother is in denial, and the child is too afraid to say anything.

Marina begins stalking Andre with the intention of harming him, but, reactions to trauma being unpredictable, engages in a torrid affair with him. He does not recognize her, and somehow she seems to find his working-class household almost exotic. She ends up using him to help with the case of the little girl by confronting her abusive father, but things get out of hand. The end of the film is open to interpretation: Will Andre seek to hush Marina or try to connect on a more permanent basis?

The excellent cinematography captures the gloom of life in this unappealing urban landscape. People are ugly to each other; women show no special kindness to other women. I don’t think there is a smile in the film.

Found Memories / Julia Murat / Brazil

Rita (Lisa E. Favero) is a young contemporary photographer who might as well have entered a reverse time machine, once you see the tiny remote village she ends up visiting. The 18 residents are mostly old people repeating the same rituals day after day and just waiting to die. She ends up befriending and staying with old Madalena, who meets every morning with the same man while he bakes bread and lectures her, after which they share a coffee at exactly the same spot. Life for them is little more than this.

Madalena can not fathom why Rita wants to take photos of her trinkets, antiques, and old clothes: for her, they are just discarded functional items. The film itself moves at a deliberately leisurely pace, echoing the rhythms of old age, but Murat wisely shoots some of these objects and old photographs that jog Madalena’s memory in slow motion, as if floating in the air. Even though the idea of an interloping photographer comes off as a bit of a contrivance, highlighting the items coincides with Madalena’s recognition that the objects of her life, indeed her life itself, have intrinsic worth. They give purpose to her existence. She becomes in her calm way content, and finds fulfillment that prepares her for death with no regrets.

Oslo, August 31st / Joachim Trier / Norway

Although Oslo, August 31st lacks the intellectual density of Trier’s earlier film, Reprise, it nevertheless has its rewards. Anders (Anders Danielsen Lie, excellent and in almost every frame) is a thirtysomething addict allowed out of rehab for one day, just before his graduation. He must attend a job interview.

Oslo is introduced beautifully in a series of still images at the beginning of this mood piece. The film proceeds to deconstruct it, to reveal its flip side. This is the urbanscape in which Anders overpartied as a privileged middle-class student, for which he is now suffering the consequences. As he tries to reconnect with Oslo, he is lost. He meets up with an old fellow addict friend who has reformed and become bourgeois, and who admits that he finds his new life boring. Anders is trying to decide whether to continue living or not: keeping on as he is, or adapting to his pal’s low-energy lifestyle.

The interview is a disaster, albeit a comic one. Anders continues to wander around the city, and runs into some old pals, most of whom eye him suspiciously. The film and the character raise questions: What is the fate of the reformed junkie? Can he ever fit into the straight world? His connection with the world he had experienced before his drug phase has become forever altered.

It Looks Pretty From a Distance / Anka and Wilhelm Sasnal/ Poland

Polish visual artists Anka and Wilhelm Sasnal train their artists’ eyes on an attractive but depressing Polish town in the middle of a scorching summer. In this post-Socialist time people are angry but don’t always have specific objects at which to vent their rage. When a scrap metal worker named Pawel departs and doesn’t return immediately, his fellow residents lose control, tearing up his home for anything of value, and going even further, even poisoning his dog. This is obviously not just about theft. Pawel returns to nothing.

It’s hard to imagine a place with less empathy. People are nasty. One couple shoves the husband’s elderly mother into a car and carts her off to some facility, no affection in sight. Economic hardship is accompanied by bestial behavior. The great mystery is the town’s river, where young boys play and which has a history of suicides by drowning. There is no sugarcoating here.

Now, Forager / Jason Cortlund and Julia Halperin / USA, Poland

A married couple, Lucien (co-director Jason Cortlund) and Regina (Tiffany Esteb) are trained chefs living in Jersey City. Out of passion and for extra money, they scour the countryside for exotic mushrooms, which they sell to fancy restaurants. Lucien especially is an expert on mushrooms, but his descriptions are relayed in the same monotone as his dialogue with his wife and everyone else. Her expressions are as limited as his speech. Their interest in mushrooms is, however, fascinating.

Problem: They are running out of money. Against Lucien’s wishes, Regina takes a part-time job in a fancy New York restaurant. Then she is lulled to a Basque restaurant (Lucien is of Basque heritage) in Rhode Island, but it turns out to be an Americanized dump. Lacking cash, Lucien, who feels abandoned, ends up accepting a well-paying one-time catering gig with a smug socialite in Washington, D.C., but he runs away from what turns out to be a nightmare. No other work can match the purity of their mushroom foraging.

Their relationship has changed. Even though the plot is novel and filmmaking good, the actors present more of a problem than range. After seeing so many New Directors films from other countries and cultures, I feel like the American indie actors often seem unreal, actors performing in an often imaginative fictional space. The foreigners exhibit more of a feeling akin to real life, with lived-in faces and less-than-perfect bodies and physiques. Perhaps it’s just symptomatic of our being a younger country with a shorter history, but I think the issue is one worth pondering.