Back to selection

Back to selection

Up All Night With Robert Downey Sr.

Robert Downey Sr.’s films are ribald, socially-conscious, highly experimental works that make Richard Lester’s oeuvre seem polite and Godard’s plot-heavy. Though he achieved cult success with 1969’s Putney Swope, some of Downey’s other, more radical works from the period are arguably more interesting, and their revival by way of an Eclipse box set is exceptional news. Up All Night With Robert Downey Sr. brings together five early films which show the director at his unhinged best, and if nothing else should prove a hedge against Downey becoming a mere footnote to his more famous son’s career.

A part of New York’s avant-garde film scene in the 60s, Downey screened his works alongside underground icons Shirley Clarke, Bruce Conner and Kenneth Anger. What he shared with his contemporaries was a patent disregard for convention and an ability to make films on the cheap. He cast his friends and family, shot on available locations, and mostly avoided sync sound. The work transcends its technical and budgetary limitations however, owing to Downey’s impudent sensibility. Plot, realism, and good taste all go out the window. His narratives are instead random, surreal, and chock-a-block full of crass humor—call them post-modern picaresques.

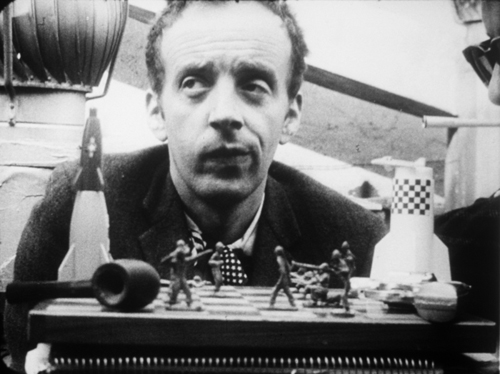

Downey’s first feature, Babo 73 (1964), is case in point. A sui generis political farce, it follows the whimsical adventures of Sandy Studsbury (Taylor Mead), the effete president of the “United Status,” who conducts affairs of state from a beach chair. “I’m morally committed to anyone who’ll vote for me,” he gleefully admits. With the help of his feckless cabinet, Studsbury makes quick work of assassinating prime ministers, bombing Albania, and congratulating himself on his job performance. Filmed in extremely unlikely locations—a crumbling house, a cemetery, a highway median—the picture makes a virtue of abstraction, like an Ionesco play shot through with Beatnik sensibility.

Downey’s next and more daring effort was 1966’s Chafed Elbows, the one masterpiece in the set. Composed almost entirely of still photographs, it’s a twisted formal cousin of Chris Marker’s La Jetée, the difference being that Downey’s photos wriggle, writhe and repeat to the rhythm of a bebop beat. It lends the film a cartoon-ish quality that mirrors its “story,” wherein every-doofus Walter Dinsmore (George Morgan) sleeps with his mother, gives birth to some cash, has a nervous breakdown, acts in an underground film, shoots a cop, defenestrates his cousin…and so on. Absurdity is the byword, and no one escapes Downey’s critical eye. Poets, parents, artists and cops are all variously derided as frauds.

Chafed Elbows successfully earned Downey a reputation, and after the curious docu-diversion of 1968’s No More Excuses (the less said, the better), he was able to finance the bigger budget, higher concept, Putney Swope. In it, the eponymous hero (Arnold Johnson) is the sole black employee at an advertising firm who gets promoted to Chairman of the Board by fluke. No sooner does he take over, than he replaces the white staff with black and embarks on a doomed crusade to marry his high ideals with big business. Downey’s first film to observe at least a few tenets of classical form, it’s naturally the one that went over biggest on release. It’s got a groovy, revolutionary spirit, but from a formal perspective it’s not half so daring as his previous work.

Downey went on to direct another cult favorite, the unfortunately not-included Greaser’s Palace (1972), and has had an erratic career ever since. In 1975 he made the nigh inscrutable Moment to Moment (included here in a re-cut form as Two Tons of Turquoise to Taos Tonight), then followed it in 1980 with the banal teen comedy Up the Academy. That he never found a solid industry foothold isn’t surprising; originality has never been an asset in Hollywood and Downey’s style is anything but derivative. His early works, nevertheless, retain their freshness, are still vital, and unequivocally those of an unruly American original.