Back to selection

Back to selection

Game Changers Part 4: Planning and Shooting

In this fourth episode of a series on the making of the low-budget independent film, Game Changers, director Rob Imbs and cinematographer Benjamin Eckstien discuss audio recording, communication between director and cinematographer, and how to plan out shooting a multi-day, multi-location project. Earlier parts consisted of an overview and then discussed fundraising, casting, camera and lighting gear.

Filmmaker: What is the size of your crew?

Eckstein: We typically have two people in our sound department every day, though there were some scenes or times of day where we had one person. We typically had an AC and another PA. On some of the bigger scenes we had somebody doing script supervision, and someone doing makeup for certain scenes. For a car scene, it was just me and Rob in the car with the actors, although we did have the sound guy to get the camera set-up. I would say it was a smallish crew, but we generally had enough people.

Imbs: The crew was just the size I like. I have an AC there for Ben, and then I talk with Ben about whether we need more. I’m lucky because Emily Curr, who is our assistant camera, is an amazing young PA. I also have a pool of young PAs who are smart and have enough experience to take direction and know what they are doing. I can really pool from them on days were we need more people. I don’t like a big crew and almost to a fault, my philosophy is to have a small crew. That’s just where I feel most comfortable.

Filmmaker: Do you have a dedicated sound person?

Eckstein: We have a dedicated sound person. The only real change – which was new to me – was that by the second day we realized that we wanted to have two boom operators on most scenes. It was partly because of how we were shooting it and the way that the actors were performing the dialog. We had a lot of overlapping dialog and scenes where people are sitting across from each other in a room. We needed to be booming several people at once, so for most of the scenes one of the PAs became the second boom operator.

Filmmaker: How is the sound being recorded?

Eckstein: The camera is recording reference sound. The sound guy is recording the two booms to a Sound Devices 702 recorder, and there was an occasional scene where we had a lav. We’re slating and that will all be synched in post. He’s also sending that to the camera, though there were times where logistically, we just couldn’t do the cable run to the camera so we used an on-camera mic as reference.

Filmmaker: What’s the shooting process for a scene? Do you have storyboards? How do you discuss what you are going to shoot?

Imbs: It’s really been an evolution. On the first day of shooting I said, “Just give me standard coverage.” We shot a scene that wasn’t pivotal, and I think we were both feeling each other out. I didn’t want to do anything really dynamic or that was a really tough shot.

And as we went along, day two, day three, we started to have more and more conversations. On day five, the night we shot the poker scene, I had a conversation with Ben, and we both hashed out [the question] “how much do we need to talk about coverage?” The next day I really started going into scenes: “Alright Ben, here’s where my heads at,” and we’d walk through the whole two or three pages of dialog. And so we’d make a shot list for each day, and it went a lot better.

In retrospect it would have made sense for me to say, “Ben, here’s what I’m thinking” at the beginning. We did lose one of our primary locations three days before shooting, so that added to some of the initial stress. But after the first few days of shooting we would plan what we were doing the night before. Here’s a layout, here’s the shot list. And it was great because when we got there Ben knew what we both had agreed on, and then he could worry about working with the AC and getting it beautiful. Then I just worked with the actors, worked with makeup, and prepped them to go in the shot order, and it just made everything feel great.

Even if you don’t have storyboards, have an idea of what you want so you can tell your cinematographer. You really want to start having those conversations, and I think what it did for me too is, Ben would say, “Do we really need this?” Sometimes I’d say, “You know what? No. We don’t need that coverage.” I could have lied then and said that we had storyboards and stuff, and I do, I have some scenes that are boarded out.

Eckstein: I think you have it more in your head, and honestly, that’s fine. I’m not used to working with storyboards and I think in a way it would have pigeonholed you a little bit because some of it had to be fluid. Some of it’s a time constraint where we realized we were running short on time and it’s, “Hey we got this coverage from these three shots, we don’t need to go overboard getting this other angle.”

Imbs: There are other days where I’ve said, “Ben I want this, I need this,” and he might even think in his head, “This is stupid Rob, you don’t need this,” but we get what I want.

I really was very selective about who I put on this crew. The movie has to be able to move. I have to be able to ask an actor, in front of everybody, “Do you think he would say that or this” and I need them to tell me yes or no. Same thing with Ben. I’ll go over to Ben and I’ll go, “Do we really need this, do you think we’ve got that covered?” I love having those conversations.

Eckstein: That is one of the benefits of a long project like this. The first few days are kind of a warm up and you make sure not to schedule the hardest and most important things on the first day because it does require a little bit of testing.

Imbs: Having made a bunch of indie films I would tell any indie guy out there” don’t schedule the most important thing the first day, schedule something really easy. I knew going in I wanted everyone to get to know each other the first day, because what’s going to make a successful film is the people liking each other.

Make sure that there is food there. Don’t just get water, get vitamin water. Don’t just get Doritos, get good food, and that energy carries through. And I did that, and I think that people are excited, they want to be a part of this film and [they know] this is important.

Filmmaker: What would you say is the hardest thing you had to deal with? And what do you think you’ll be most proud of?

Eckstein: I think the hardest thing for me was that some of the locations weren’t ideal. But in a way that was the most rewarding thing. The last scene we filmed, we were already going late to it as the previous location had gone late. It was a bedroom scene, two actors in bed, and it was the smallest bedroom I think I’ve ever seen. And I walked in there and I was like, “You’ve got to be kidding me.”

Imbs: I may have lied about the size of it…

Eckstein: It was a buddy’s place, and he was in the process of moving out, so there was almost no furniture there. I almost came downstairs and said, “There’s just no way we can do this, I know what you’re trying to shoot, this is supposed to be the female lead’s place, and I don’t buy it that this is a place she’d live in this teeny tiny apartment.” But it forced me to think, How do you shoot this, how do you light this, how do you set this? I think in the end the scene looks pretty good. The performances were good, and I did have to squeeze myself into a corner of a room and balance the camera on a sandbag because a tripod wouldn’t fit back there, and we had to eliminate a jib shot that we’d talked about, but in a way it was fun. I think my work experience prepared me the best for this, because I do a lot of interview shooting where you walk into rooms and say, “This room sucks, how do I make this look good?” That’s kind of what I’m used to.

Imbs: The hardest thing was locations. I would recommend that directors not take on the burden of locations. Get someone who’s a line producer, even if you pay them a couple of thousand dollars a week, they will make your life perfect because they will do all the things that need to be done. They’ll make all the phone calls and get all the locations squared away, and you won’t have to worry about any of that crap.

Eckstein: I’m very proud of what we did, but think of what we could have done with a great location.

Imbs: That’s true. We do have a location that is probably my second favorite shot of the film. We needed a business park where one of the main characters was going at night to hack into a wireless network. It was just him in a car, and I thought of this place and I said to Ben, “You know we really don’t have the right to shoot there, it’s a business park, but let’s just do it.” So we went there and we got just absolutely gorgeous stuff. The buildings are monolithic, they just look gorgeous. So I agree with Ben. Get good locations.

I guess my favorite thing was shooting with the NEX-FS700 at 240 fps in my childhood bedroom. It was a culmination of what this film is about, coming from a lot of inspiration from my youth. Shooting extremely high frame rates that we never would have been able to shoot at before the F700. It was so exciting.

It sounds like such a cliché to say when you’re talking about your film but it is [true]: we’re so lucky to be indie filmmakers now with all of the things we have, the tools we have. I watched that shot over and over and over again, and I just can’t believe this is in a movie that, when it’s all said and done, will have a budget of less than 30k.

Filmmaker: Are you using the FS700 just for that?

Eckstein: We knew that there was this one shot that required a high-speed camera so we bought it in to town just for that one shot.

Filmmaker: How have you been managing your shooting schedule?

Imbs: This is the second thing I would tell people: get the best actors you can. Don’t just get your friends – and I say this being someone who has gotten my friends before. Get actors who are working, who are good. I would recommend going for stage actors because everybody thinks they are big, but they can really bring it down small on film, and you have to be a lot smaller in film. Establish a relationship with them, but make sure to get their schedule way ahead of time because it’s a pain in the butt. I’m lucky that two of my main actors have taken jobs to be available for stage and screen.

When it comes to scheduling, I plan as far ahead as I can, what I want to shoot based on my DP, and the availability of the crew. We aren’t a big budget film where I can just say, “I’m paying my guys and they’re available whenever I want.” I ask all of my actors to give me all of their availability and I crack the whip constantly and they finally give me their availability. Even if they don’t know that much, they can say, “I don’t know about any other day, but I can’t shoot this day.” It starts to give me an idea and I can look at my entire breakdown of every scene, who’s needed, and what locations, and I literally just sew this thing together.

I’ve both loved and hated that. I’ve loved it because it’s so rewarding when I finally can say, “This is what I’m shooting this week.” I feel good about it, and I wouldn’t trust anyone else to do this to tell you the truth.

Filmmaker: How do you keep track of all this?

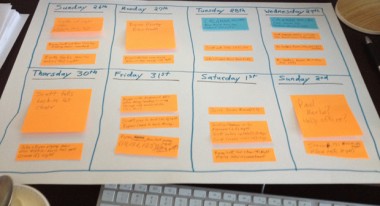

Imbs: I’ve got my availability in one Numbers document. In Excel I’ve got the scenes I need to shoot, what we have shot, what we are definitely shooting, what we are thinking of shooting, and then I have big pieces of paper that I actually tape up on my wall. I’m a big planner; I’ve got day planners and cork board all over my house. I have every day written out, probably about 5 foot by 5 foot each, and I just tape them up on my wall and I write little scenes on Post-its; the scene, the people, the day, and it’s easy because it lets me move them around.

There’s probably a good way to do this digitally, but I just like to work with my hands sometimes. I move them between days based upon availability until I think, “This is the most I can shoot,” or “this is appropriate where I think my actors need to be emotionally.” There’s some things I don’t want to shoot until later because I want them to get the character more.

Then I send it out to everybody, and we go from there.

Filmmaker: Any other advice to anyone who wants to undertake this kind of venture?

Imbs: If someone has never made an indie film, and they’re jumping right into a feature, what I would say is: Don’t. Do a 48-hour film first. Get your friends together and shoot something and edit it. If you do have a little experience and you’ve already done that, and you want to really move to the next level: pay actors, pay people, pay a crew, utilize IndieGogo, and if you have something that’s good, if you have a great idea and you push it, push it, push it, there are people out there who really want you to be successful. I just believe it, because I’m one of those people. And so if you have a good idea, try to get money online. Any money is better than no money.

Definitely have a script. As someone who’s made movies years ago without a script; definitely have a script. Ask, “How much do I need to do this?” and really think before you do something. Don’t go to the point of thinking so much where you don’t make the film, because some people I know have done that. But really think about what you’re going to embark on, and don’t lie to yourself because you’re going to have to make up the cash, and the chaos, and your relationship with your significant other, and your nine to five.

You really need to think about that stuff and don’t let the glamor that is “I’m a movie maker, I’m a director” [take over].

Eckstein: There’s nothing glamorous about this

Imbs: There isn’t. I actually hate people who think there is. I kind of love the blood and guts of it.

Eckstein: I don’t know if I pissed Rob off last week when I tweeted something about how corporate video is a thousand times more glamorous than making movies. And I wasn’t saying that as a dig to you.

Imbs: I don’t need to do this movie, I have a 9 to 5, I have a girlfriend I love, I’m very happy. I see films as an opportunity for me to truly face fear because it is very hard to deal with all these different people, to get to know all these different personalities, to write something, to take your creative ideas and put them out there, to be judged. To possibly fail. I just love the challenge. Whenever I make a film I feel like I always come out a better person at the end of it. And that might sound sort of, what a filmmaker would say, but I really believe it. I just get to know some more people and my relationships are stronger and I become a better filmmaker.

Eckstein: My answer might be a little more practical and less meta. But basically I agree. I think that making short films is not only a great jumping off point, but it’s also potentially a better way of getting your stuff seen, just because people will [watch]. If you look at a Vimeo video and you see it’s five minutes long, there might be more people that will watch that than if they see you uploaded a 90-minute movie.

Making shorts is great: you can almost do it with no money because you can really work on volunteers. Once you get up into a 15, 18 20, 25-day shoot, that’s when your favors that you are calling in start to run dry. It just takes money to make movies. There are certainly people who figure out how to do it with next to nothing, but unless you are very lucky, or you plan a concept that works to the benefit of having no budget, there are just very simple things like food and insurance that cost money.

Imbs: There is a baseline and you just need money to make a movie. Like you need insurance if you’re going to shoot places. They just won’t let you without.

Eckstein: You have to be the ultra-endurance athlete that’s ready for the very, very long haul of it.

Website: The Game Changers