Back to selection

Back to selection

‘Til the End of Time

While the title of Eve Sussman’s (and her collaborative team Rufus Corporation’s) whiteonwhite:algorithmicnoir –– shown as part of New Frontiers at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival –– refers to a seminal abstract artwork dealing with space, the video itself is all about time. In fact, this experimental piece’s apparent story about an American geophysicist named Holz (Jeff Wood) working in a post-Soviet industrial metropolis called City-A has no fixed time at all. That’s because the sum of the video’s parts aren’t just greater than the whole –– there is no whole. Through an algorithm, which Sussman has dubbed “the Serenity Machine,” the various elements –– nearly 3,000 video clips, 80 voiceover parts and 150 music cues — are continually re-edited and rearranged based on a series of computer generator tags. Focused on for any 20-minute stretch, whiteonwhite:algorithmicnoir’s haunting landscape of alienated lives lived in a corroded industrial landscape seems perfectly logical and chronologically sound. But contemplated across hours, concepts of plot and narrative unity fade into a blur.

In some ways whiteonwhite:algorithmicnoir began as a joke. As a multimedia artist, Sussman gained fame in the art world for her choreographed, video deconstructions of great masterpieces of Western art. Her 2004 looped video 89 Seconds at Alcázar is an elegant reframing of Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas, and her 2007 Rape of the Sabine Women video turns the horrors of Jacques-Louis David’s 1799 Roman-inspired painting The Intervention of the Sabine Women into a ’60s cocktail party resplendent in the International style. Sussman recounts to the arts website Glasstire that when friends pushed her about what her next painting inspiration would be, she cited, half-jokingly, Kazimir Malevich’s iconic 1935 Suprematist work, White on White. But over time the joke grew more interesting as Sussman pushed the idea of space past purely aesthetic considerations into more literal concerns, like outer space travel. As Sussman told Artnet, “My interest has always been in discovering new ways to switch up the established narrative arc of things, to allow for individual interpretations of ideas or dynamics that might seem quotidian by suggesting alternative possibilities, and giving viewers the space to develop them.”

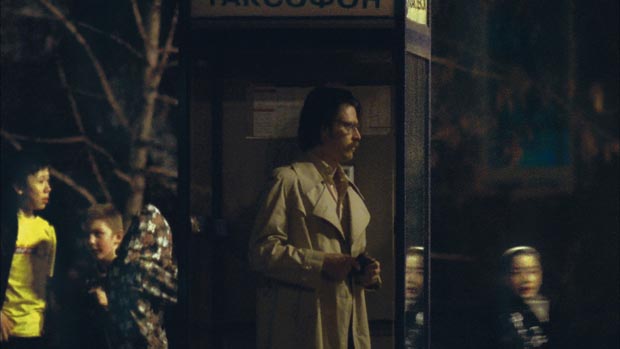

Sussman’s exploration of space first took her and her collaborators in 2007 to Kazakhstan, where the Russian rocket-launch site Baikonur Cosmodrome is located. But after being held by the local police for filming around a military base, the group took a more general approach, returning to this area to film various landscapes and scenarios, eventually naming the project as a whole “whiteonwhite.” The qualifying label “algorithmicnoir” defines the dual structural principles that govern the video itself. Mechanically the work is controlled by the computer algorithm that arbitrarily determines its edit. Thematically Sussman obeyed the stern rules of film noir. Here, traditional L.A. noir has given way to a post-Soviet noir, a world in which inky night is replaced by industrial gray, and tough-guy cynicism is turned into information-age fatigue. A running gag through the piece is Holz attempting, on the phone, to acquire approvals only to be told by some mechanical operator he doesn’t have the required authorization.

Sussman’s work, however, also extends the tradition of smart sci-fi, works like Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville (from which the term City-A is derived), Andrey Tarkovskiy’s Stalker and even to some extent Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, all stories in which the conventions of history and geography, time and space, have been purposefully disoriented. While City-A (played by the actual Caspian Sea town of Aktau) is clearly a contemporary Russian city, its design and fashion feel frozen in ’70s style. The anachronistic flourish is partially intentional, but partially the effect of the new world order, in which fashion and design, rather than being markers of changing history, operate on a timeline all their own. In the same way that the piece as a whole radically alters our sense of cinematic time, the look and feel of City-A seems to float free of Western history, apparently operating on an algorithm all its own too. Talking to ArtNet, Sussman noted, “The spaces in our footage are beautiful, in a weird way — there is such a strong geometry to them, and they seem so full of mystery because they look so different from what we’re used to seeing in Western Europe or America.” In many ways, the same thing could be said of what history has become in Sussman’s new world order.