Back to selection

Back to selection

Cannes 2013: Payne’s Nebraska and Puenzo’s Wakolda

Nebraska

Nebraska Alexander Payne’s Nebraska is an impressive achievement, a fresh and innovative take on that most familiar of genres, the road movie, one that takes conventions about the American heartland and turns them on their head. It’s also a story about a father and son learning to see and understand each other for the first time.

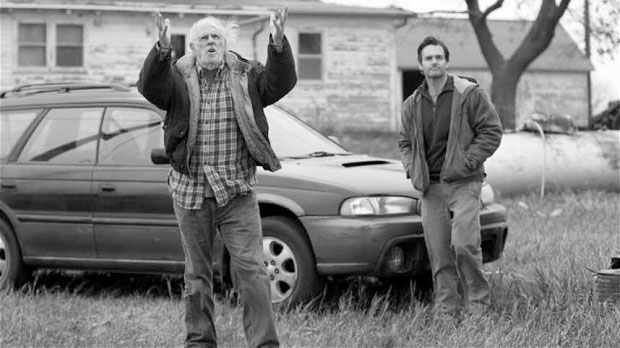

The film opens with a shot of Woody Grant (Bruce Dern in what should be a performance that collects numerous awards) shuffling purposefully down a Billings, Montana, highway, his scraggly beard, limping gait and weathered face suggesting a man who has struggled for the little that he has. But this is undercut when we realize that Woody’s actions are part of a routine. He has received a letter stating that he is a “winner” in a scam magazine sweepstakes and is determined to collect the million dollar prize in Lincoln, Nebraska. And he is stubborn enough to keep trying, no matter how much his domineering — and hilariously unfiltered — wife might complain. Eventually, his younger son, David (Will Forte), relents and agrees to drive his dad, in part to shut him up, but also to escape from some of his own issues at home, including his own uncertainty about a dating relationship that has fallen apart, mostly out of inattention than anything else.

The road trip narrative sets up the central plot, a visit to Woody’s hometown, Hawthorne, Nebraska, where they spend several days with Woody’s family. The scenes in Hawthorne allow David and his brother, Ross (Bob Odenkirk), to learn more about their father and introduce the film’s comic depictions of the American heartland. Payne, as in About Schmidt, depicts the Midwest not as a place of kindness, generosity, and wholesomeness, but as a site where petty jealousies often last decades and where the locals selfishly try to make a quick buck off of the gullible Woody. These encounters seem to show the limits of going home, of the distractions — Sunday afternoon football games, watching cars pass by — that allow families to avoid genuinely conversing with each other. But David and Ross are also able to learn about the more heroic and kind acts of their father, things that had gone unspoken, in part because Woody never seemed to need to make a fuss.

While aspects of Nebraska may recall some of Payne’s previous films — About Schmidt is also a road movie that involves family members reconnecting, and The Descendants also depicts a character who must come to grips with his past — Nebraska startled me with its ability to allow its characters to revisit the past in a natural, unforced manner. Payne brings out excellent performances from Bob Nelson’s insightful screenplay. Dern is natural as the often taciturn Woody, and Forte was a revelation as his kind, if somewhat less than successful, son, while June Squibb takes what could have easily been a one-note performance as Woody’s blunt-talking wife, and provides her with a genuineness and familiarity. The black-and-white cinematography works well in capturing the wastelands of Montana, South Dakota, and Nebraska, making the landscape seem even colder and more remote. Nebraska is a powerful little film, one that borrows from the tropes of the road movie while still having something new to say.

Lucia Puenzo’s Wakolda is an engaging historical drama featuring a young family in Argentina in the early 1960s that befriends a mysterious and charming German doctor. Initially, the wife, Eva, and the couple’s daughter, Lilith, accept the man because of their shared German heritage and because of his promises to help Lilith — who is short for her age and teased relentlessly at school — to grow more quickly. But as their interactions deepen they begin to realize that the doctor is Joseph Mengele, the notorious Nazi scientist who conducted countless experiments on concentration camp prisoners in order to research his theories about genetics and racial purity.

Wakolda is based on Puenzo’s popular novel of the same name, and her ability to draw out subtle observations about the Nazi project is clear throughout the film. One subplot involves Mengele’s offer to help the father, Enzo, manufacture dolls that he has been designing in his spare time. Where Enzo seems to lovingly craft the dolls, placing beating hearts inside them that he hopes will render them unique, Mengele’s approach is something closer to mass production, where every baby shares the same traits and no imperfections of any kind. The result is an uncanny row of identical, plastic, artificial dolls that evoke Mengele’s more sinister ambitions.

Although the film is based on true events, it serves less to offer a complete historical account of Mengele’s years hiding in South America — Mengele’s time in Bariloche with the family is considered to be the least known period of his post-war hideout. Instead Wakolda uses one family’s experience to explore Argentina’s complicated past, in which many families and communities were complicit with hiding Nazi war criminals like Mengele. In a few places, Wakolda seems to struggle with offering a degree of complexity to characters outside the family (most of Mengele’s collaborators are not depicted with any detail), but for the most part, it succeeds in depicting how one family might have initially been seduced by the doctor’s charms and his promises of a better life and better health.