Back to selection

Back to selection

Andrew Ellard on Writing for Film and Television

This is the first of a three-part series on the independent horror film AfterDeath, which is currently in post-production. The first part is an interview with writer Andrew Ellard, while the following parts will feature an interview with producer and co-director Gez Medinger.

In school, Andrew Ellard thought he wanted to be a cartoonist, but it took a long time and a “not very successful A-level art” for him to realize that he actually couldn’t draw. This led him to a second revelation; that he wanted to tell stories — he’d just picked the wrong medium.

After finishing school, Ellard was hired by Grant Naylor Productions to write web articles and news pieces about the Red Dwarf TV series. When the movie of Red Dwarf went into production he started doing notes for Doug Naylor, the writer of the film. Naylor told him, “These are the best script notes I’ve ever had in my life.” Says Ellard, “I was aspiring to write, but I didn’t know that script editing was a job.”

Ellard went on to work at ITV, continuing to write script notes for different projects. He’s written or acted as script editor for several British TV series including Doctors, Life of Riley, Cardinal Burns and The IT Crowd. “I thought drama was my thing… but now I’ve become this jack of all trades where I do a little bit of everything, a little bit of drama, a little bit of comedy and a little bit of horror”

While he has a lot of experience in television, AfterDeath is his first feature project to be shot. Ellard recently talked to us about the process of writing the script and the differences between writing for film and television.

Filmmaker: How did you get involved with AfterDeath?

Ellard: Co-producer Gex Medinger had a treatment of a story that was very, very loosely inspired by Jean Paul Sartre’s No Exit, which I hadn’t read until he gave it to me. He sent the script to me for notes and I liked the premise — a horror movie about characters waking up in the afterlife — and the beach house setting was there, but, and he’ll hate me for saying this, I didn’t like any of the characters, and about 90% of what happened.

So I sent him a list of what he could do to fix it, but I put a PS in the middle of it saying hint, hint, “this is exactly the kind of thing I’d love to get on board with” and bless him, with no ego whatsoever, knowing that they wanted the best story they could direct, he said, “Alright, we’ll give you a shot at it, we’ll hire you on to do it.”

I pitched them my ideas for what I would do with a story with the same kind of setting, what characters would be in it, what world it would take place in, what the rules where and what the outcome would be and they dived on it, they really liked it, so very quickly I was churning out a draft for them.

Filmmaker: Did they give you any constraints on location, and characters, or did you have free reign over the changes you made?

Ellard: They didn’t give me many constraints, but we both mutually understood that there were constraints. They were very clearly going to go off and shoot this as a one-room thriller. Gez had been to the location and they found this brilliant house on the coast, and it was just so weird. One of the best things was the house because it had this set of rooms that didn’t seem to belong together. The bedroom seemed to belong to one family, while the other bedroom seemed to belong somewhere else. The toilets were horrible; they were like toilets in a seminary or a community hall. It was such a weird collection of rooms with all this mad furniture and none of it matched or went together. It was all from different eras. You look at this and you think, “This is like some madman has built it on the memories and back stories of ten different people,” or as the movie turned out, five.

That’s all incorporated, that’s part of the story now and that was inspiring.

On the location video there was a lighthouse in the distance and I immediately dived on that, because that was something that just fit with another idea that I had about the light of hell. It just all fit together, so although there were limitations, the limitations were sort of the most inspiring thing about it.

Filmmaker: They had the location before you started writing?

Ellard: They did. Gez had been over to reccy it and shot video of the whole thing. There’s a great moment in the reccy video where he tilted up and there’s an entrance way to the attic space, and it’s literally a crawl hole. It’s very small, it’s completely black, you can’t see what’s behind it and I just went, “Oh yes” because it’s like how in Alien Ridley Scott keeps framing scenes with the door open in the background and it just adds to the tension of the movie. You don’t even know why, you just aren’t comfortable because there’s an alien loose in the ship somewhere and he’s left the door open or there’s a vent in the back of the shot, and you can just feel access. Things like that you just grab for because it’ll make everything you’ve got on the page richer.

Filmmaker: Did you change the story in any major ways?

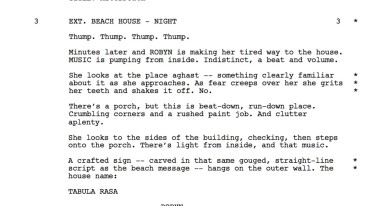

Ellard: The treatment didn’t have the characters realizing they were dead until about half way in, and I just felt like it’s going to be in the promotion, it’s going to be on the poster, it’s the thing you sell the movie on. So if nothing else, having the very first scene being the lead character come out of the ocean, check her pulse and realize what’s going on means you blow past that and have the interesting conversations about what it is to be dead and what it means to be where they are, and what regrets they have. You can dig into that stuff faster and deeper, while also attacking them with a monster. I’m looking forward to seeing a cut, I can’t wait actually, I’m really excited about it.

Filmmaker: How long did it take to write?

Ellard: I was fitting it in between other jobs, but I think I wrote the first treatment in October and they shot it in February. We went through a lot of drafts given how little time we had.

I really like to get it right but you also have to be realistic about it. I had a board with all my notes on index cards and getting that together was like writing the first draft. Then I did a treatment off of that, so that’s sort of a second draft. We nailed the story down and the guys provided really useful feedback and kicked it around. That came back and I did a draft, and I did another draft and then notes came in.

It worked exactly how it was supposed to, in a concentrated time period. Every draft was better and the shooting draft was, I think, very solid indeed.

Filmmaker: You mentioned a board. What is that and how does that work?

Ellard: I kind of got sucked in to Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat, but you find the screenwriting tips that work for you. There’s a lot of good advice out there but often it’s the same advice wearing a different hat. You just need to find the techniques that get you to write your best. I’ve got quite a structure-oriented mind, so I can skip a lot of things that Save the Cat has in it like, you must put on the card what’s the plus and what’s the minus, what’s the turn.

I know Gez sometimes uses terminology from a completely different book and I look utterly bewildered, but as a television script editor structure’s really my thing, it’s what I’m obsessed with. I want stories to have drive and characters to have goals. The thing from Save the Cat that’s really useful is sub-dividing the movie, and getting it into those four chunks; Act I, Act II part 1, Act II part 2, Act III. Then even splitting that down into “the bad guys close in,” and all those “all is lost” moments’ and all of that. It just tells you whether the thing you’re putting together has its balances in the right places.

But I never use the same process twice. The next job I do I will do it in a completely different way, but it will always be some version of Save the Cat because those structures are really useful to me.

Filmmaker: Were you on location for the shooting?

Ellard: Not at all. The last thing you want is another pair of feet tripping you up while you’ve got a seven-man crew in this small house.

The guys had been very respectful of the draft. I already know, based on the trailer, that what they shot isn’t literally word for word what I wrote, but it’s absolutely the story we all agreed to tell, and the characters we agreed to tell it with, and the incidents and the accents, so I’m not going to get to upset about a line here or there.

Filmmaker: So you haven’t seen it at all?

Ellard: Well I know the broad strokes, because Gez and co-director Robin Schmidt have shown me a few scenes, but I asked not to be shown more because they already want to fix loads of it. The most useful thing I can do is wait until they have a cut that they think is starting to close in on what they want it to be, and then I can come in and sort of do a set of writer’s notes on it, which won’t be encumbered by “Oh, I remember that bit.” By that point I’ll have almost forgotten the script, so you just look at whether it works as a film and then provide whatever help you can.

It’s the same way as I fed in to casting; I didn’t have a say in it exactly, but they sent me all the tapes and I pushed really hard for one particular person. Not everybody on films is like that; a lot of the time you will just hear, “I’m directing it so that’s the end of the argument,” rather than winning the argument. These guys just didn’t do that, we were all on the same page.

Filmmaker: Is this your first feature film?

Ellard: It’s the first one that I’ve had made. I’ve written three or four that I’ve been paid to write, or done in deals. Then there are some really terrible early screenplays that thankfully were written on a computer so old you couldn’t even convert the files at this point.

Filmmaker: Was this experience any different from your television experience?

Ellard: Absolutely. There is no question that with films the director is more in control, and I don’t know whether I like that.

Filmmaker: Why is there more director control with film?

Ellard: With all the TV I’ve done, most of the writers I’ve worked with are writer/show runners, it’s their show and so they have a significant influence on everything; on casting, on who is directing, and being useful on the day as changes and fixes happen. With film, I do think the auteur theory has a lot to answer for in terms of how much power is put in one place, but then I would say that; I’m a writer. Feeling aggrieved is sort of what we do.

I think TV is nicer to writers, but from this experience, if they were all like this I’d love to write a lot more movies.

Filmmaker: What are you currently working on?

Ellard: At the moment I’m rewriting a stage musical, which I’m really excited about because I don’t have to get out the rhyming dictionary, I’m not doing the lyrics or anything but the story. It’s an adaptation so I’m looking forward to digging in to that. We just nailed the story down and we nailed it with such a triumphant punch in the air that you just went “This is going to work!” So I’m thrilled about that.

I’ve got a sitcom at the BBC that I’m working on with a couple of other people. I’ve also got a sitcom with ITV which I’m really hoping to get launched. That seems to have got a really good response there, so it’s all irons in the fire at the moment.