Back to selection

Back to selection

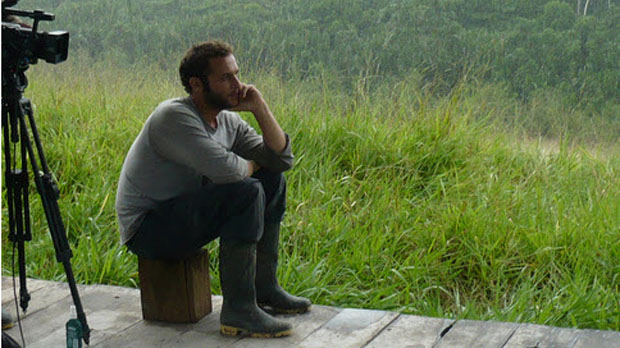

Michael Kleiman on Web, Connectivity, and Social Documentary

Only 32% of the world’s population has access to the Internet. That figure, coming from the organization A Human Right, means that 4.6 billion people are effectively left out of the Information Age that most of us take for granted. Individuals and organizations across the world are working to ameliorate that and spread online connectivity into underdeveloped and rural areas from the U.S. to Kazakhstan. And films like Tiffany Shlain’s Connected (2011) are starting to probe what can happen to global consciousness when the collective wisdom of the world, not just our meager social networks, are finally truly linked together.

But how to do it? Perhaps the best-known group is One Laptop per Child, founded by Nicholas Negroponte in 2006 to provide Internet-connected computers to children throughout the developing (and developed) world. With such an ambitious commission, the group has not been without criticism, and it seemed like the perfect subject for documentarian Michael Kleiman’s second feature film, Web.

Kleiman is one half of the production company Righteous Pictures. His first film, The Last Survivor, was about the experiences of survivors of genocide in the Holocaust, Rwanda, Darfur, and the Congo. It incorporated a strong element of social proactivity for the prevention of future such calamities, and its rollout, in line with Righteous Pictures’ progressive social consciousness, sought to educate and empower its audience to actually affect policy.

Kleiman talked with me about how he and his production partner Michael Pertnoy go about this process and what he hopes to accomplish with his new film. Web will premiere at the DOC NYC Film Festival on Saturday November 16th at the IFC Center in lower Manhattan (though it has already had some private screenings, discussed below). Both Kleiman and Pertnov will be present for a Q&A.

Filmmaker: Can you tell me about your background and how you got involved with Righteous Pictures?

Kleiman: My story with film really starts with Home Alone. I was probably around seven when I saw that movie and for months after all I would do was imitate Kevin McAllister applying aftershave and screaming into the mirror. That was enough to start a lifelong love affair with cinema. I started making my own movies in middle school, continued in high school, and went to college at the University of Pennsylvania where I majored in Cinema Studies. Penn is where I discovered documentary. It was also the time when I really became interested in policy issues and I saw documentary as a way of fusing my passion for film with my desire to help foster social change. Penn is also where I met Michael Pertnoy. Michael and I were in a production class together our senior year and co-directed a few student shorts. Shortly after graduating, Michael started Righteous Pictures, which really embodied that idea of fusing film production with social action. Michael and I started working together on our first film, The Last Survivor, in 2007 and have continued collaborating since. Righteous Pictures has grown as part of that process.

Filmmaker: It can be difficult for social issue films to translate into the real world and affect actual social change. What strategies or tactics have you employed to make sure films like The Last Survivor reach beyond the choir?

Kleiman: I think it starts with a recognition of what film does well and what it can’t do on its own. Film is great at helping people see the world from someone else’s perspective and understand how issues that have no effect on their own life can have deep and lasting impacts on someone else’s. That empathy piece can be very difficult for activists and advocates to achieve, so film can be a very helpful tool. Where I think film fails on its own is actually making a difference in policy; change requires collaboration. With The Last Survivor (which follows the lives of survivors of four different genocides) we were very conscious of that and worked directly with non-profit partners around the country and around the world who could screen the film and then immediately offer audiences opportunities to take meaningful action that affected the issue – whether it was working to get a particular piece of genocide prevention legislation passed, working to improve genocide education in nearby schools, or working with local populations of refugees who had recently been resettled to their communities. Understanding an issue and having meaningful conversations about it is very important, but in order to make a difference on policy, you need to engage your audience in action.

Filmmaker: So now you’re on your second feature. Where did Web originate? What was your relationship with the One Laptop Per Child program?

Kleiman: The opening sequence of the film chronicles the origin of Web pretty accurately: I read Robert Wright’s book Nonzero, which focuses on how technology has catalyzed globalization since the creation of the first stone tool. Shortly after, I saw President Bill Clinton speak on the subject of interdependence. He called on my generation to create the type of global dialogue and mutual understanding that could lead to productive global collaborations. I saw the Internet and technology as a really important piece of that puzzle, bringing more and more people to the table of ideas as information technology spread further around the world. I wanted to make a film about that idea but needed a story. A few years later I learned about One Laptop per Child and the idea crystallized.

My relationship with OLPC started with an email. I sent Nicholas Negroponte an email telling him I wanted to make a film about the organization, asking his advice on a location and whether he’d be willing to introduce me to the people on the ground who could help me figure out some of the logistics. He wrote me back very quickly suggesting Peru and introduced me to people at the Peruvian Ministry of Education who helped me make the necessary arrangements to film in schools. Because independence was very important to us in the process, we tried to limit our workings with OLPC. Both Nicholas Negroponte and Walter Bender were kind enough to sit for interviews, but that was pretty much the limit to their involvement with the film.

Filmmaker: What about financing? Did it all come through grants and sponsors? How long did it take to put together?

Kleiman: This was a very long production process. When all is said and done it took about four years from the first shot to the final mastering. Initial funding came from government grants. I received a Fulbright Grant from the State Department to go down to Peru and then some additional grant funds from the U.S. Embassy in Lima. I also got a ton of support from generous donations through NYFA (our fiscal sponsor) and a great group of friends and family who contributed through Indiegogo. Once I returned from Peru, Kevin Iwashina came onboard the project as Executive Producer and made an incredibly fruitful introduction to Stefan Nowicki and Joey Carey at Sundial Pictures, who ended up financing the bulk of the picture. We also got some great support from Associate Producers Mischa Weisman and Abe Schwartz, not to mention a host of production companies like Harbor Picture Company, Flavor Lab and Aluzcine who contributed critical services to the film.

Filmmaker: What was the shooting process like? Any surprises or particular challenges?

Kleiman: Like any long production process, there were certainly some hiccups in the road. What made it difficult with this film was the isolation of the locations. In order to get to Palestina (the village in the Amazon), my crew and I had to take Peruvian air force cargo flights that only left from Lima every 15 days. One of our shoots was delayed for a month because the air force diverted its planes to help with aid missions in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Chile. And then of course, once we got to the village we were left to our own devices in solving any technical issues that came up. Fortunately, I had great support from a wonderful team in Peru that was amazingly resourceful.

On the interview side, we were operating with a subject matter that was constantly changing. We had opportunities to interview some really incredible people like Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales, Foursquare founder Dennis Crowley, and “the father of the Internet,” Vint Cerf. As we were preparing for the interviews, it seemed like every week a new story would break that was incredibly relevant, whether it was the Arab Spring or WikiLeaks. Obviously just because we finished conducting our interviews, the world didn’t stop changing. So keeping the film current through such a long production process was definitely a challenge, but one I think we managed very successfully.

Filmmaker: What are some of the problems or complications that you’ve seen from connecting these children to the Internet? Is it all homogenization or are there other nuances that need to be worked out?

Kleiman: I think the biggest problem has to do with technical issues. Just as my team and I were left to our devices when we had camera issues, when a computer breaks or when a router breaks, there’s no Best Buy or Genius Bar to go to for support. Any issues that come up can be difficult to fix. This issue is front and center in the film. When I arrive in Palestina, I find that the Internet satellite I traveled so far to document was broken and had never actually worked. The story there becomes about some of those difficulties in bringing connectivity to such an isolated location.

Filmmaker: We were talking about the social impact films like these can have, and so much of that comes through the distribution plan and outreach efforts. Can you talk about how you’re handling that with Web and what you hope the film will accomplish?

Kleiman: As far as social issues go, Web is a bit tricky. One of the things we tried to do with the film is take a balanced approach to connectivity, highlighting the power it can have in bringing people together but also some of the ways it’s chipping away at some basic human values – community, friendship, etc. Part of our goal with the film in this case is to get people to reflect on how their own lives might be a little too dependent on connectivity. That being said, I do think the film shows how powerful connectivity can be in places like the villages in the film that are very isolated from the rest of the world. Certainly, you see the desire they have for this kind of access to communication and information. We’ve formed a partnership with an organization called A Human Right whose mission is to bring Internet access to the nearly 5 billion people around the planet who are currently living without it. We hope that after seeing the film, audiences will want to get involved with some of A Human Right’s initiatives to address the global digital divide. In terms of reaching a wide audience, we’re taking advantage of some of the natural partnerships we’ve made along the way. Wikipedia was kind enough to include a short clip of the film as part of their fundraising efforts last year, which helped us engage a really wide international audience. We hope to continue to work with them to reach an audience who cares deeply about access to information. We’d also love to partner with other big tech companies as we roll out the film. The other partnership that I’m really excited about is our work with the U.S. Embassy in Peru. With their support, I’ve have had the opportunity to screen the film in small communities in Peru (including the two featured in the film) to engage people on the other side of the digital divide on this issue and get them involved in the conversation, which is a very important piece in my opinion.

Filmmaker: What’s next for you?

Kleiman: Speaking of social impact, I recently started working toward a Master’s degree in public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. My goal is to learn how policy is created and evaluated so I can think a lot more concretely about how film can be used to influence those policies and achieve social change. As you said, it’s certainly not easy. That being said, I do have a few documentary projects that are still early in development, including another collaboration with Sundial Pictures about a growing field of design called biomimicry, which is all about copying design ideas from nature to make our world more sustainable.