Back to selection

Back to selection

Digital Motion Picture Cameras in 2014: The Next Chapter

Welcome to Filmmaker Magazine’s fourth annual digital cinema camera round-up. Each year for reasons of publishing schedule, this overview is written on the brink of the big NAB show in Las Vegas. By the time some of you read this, journalists and bloggers will have breathlessly uploaded each and every scrap of breaking news from the frenzied show floor, saving you the airfare, sore feet, and those Vegas cab fares calibrated to expense accounts.

But what do these splashy product introductions mean? Do we need to trade up our cameras? How soon? Are more resolution, bit depth, frame rates, color space even critical to what we do? I offer this year’s camera round-up as a snapshot of where cameras stand as we head into this year’s milepost NAB — and a guide to where I think they, and we, are going.

Four years ago, I titled Filmmaker’s first digital cinema camera round-up, “Digital Motion Picture Cameras For The Rest of Us.” (Published as “Does Size Matter?”) I mentioned the advent of HDSLRs, citing the example of Canon’s 7D used to film Lena Dunham’s breakthrough Tiny Furniture. New cameras on the block were Sony’s NEX-VG10, NEX-FS100, PMW-F3; Panasonic’s AG-AF100; RED’s Epic-M; ARRI’s Alexa; and Aaton’s Delta Penelope.

2012’s camera round-up, “Good Things in Smaller Packages,” noted shrinking cameras, improved HD from DSLRs, and the advent of 4K and Ultra HD. Welcomed were the Sony NEX-FS700 and F65; Canon EOS 5D Mark III, EOS C300, EOS C500 and EOS-1DC; Nikon D800; ARRI Alexa-M and Studio; and RED Epic-X and Scarlet-X. A banner year for bread-and-butter cameras.

Last year’s round-up, “Back to the Future with 4K,” looked at advances pulling us towards 4K, including pixel count, sensors, lenses, digital media, frame rates, compression and latitude, camera design and control, and post workflow. New cameras included Sony’s F5, F55, and NEX-EA50. I was skeptical towards the Chinese KineRAW S-35, Blackmagic Design’s Cinema Camera, and Panasonic’s 4K modular “balsacam,” mocked-up under glass at NAB. I ended on an admiring note, describing not a new camera but monitor/recorder concept: the disruptively affordable Odyssey 7 from Convergent Design, with flexible touchscreen controls as simple to operate as an iPad.

TURNING A CORNER

A lot can change in four years, as the thread of these topics indicates. Scrappy nofilmschool recently pointed to the fact that three of five 2014 Oscar nominees in Directing and Cinematography were ARRI Alexa projects (the remaining two in each category, 35mm ARRI Arricams). For Best Picture, the Alexa-Arricam ratio was greater than 2:1. (Whither Panavision?) Meanwhile, Debra Kaufman’s recent obituary of the era of big film labs makes clear that we’ve decisively turned the corner on the analog chapter of cinema history. Think 1927 and the arrival of sound.

What happens to revolutionaries who win? They shed their sabers to form the new establishment mostly. I took the ten all-time highest grossing films worldwide and sorted them by date. The three most recent originated on ARRI Alexa. Two others were shot on Sony HD cameras. Meanwhile RED Epics are the recent camera of choice for blue-chip directors like Peter Jackson, Steve Soderbergh, David Fincher, Guillermo del Toro, Sam Raimi, and Ridley Scott.

That leaves most of the technology churn, the red tide of disruption if you will, to the minor leagues, those farm teams of low-budget, student, and indie filmmakers who populate festivals like Sundance and SXSW and fill the channels of YouTube and Vimeo. Plus ça change…. the more this is an exciting place to be!

IN MEMORIAM

All of the cameras mentioned above are still active products, save for one. This is the first year I’m sad to report the death of a digital camera project, Aaton’s Delta-Penelope. Days after last year’s NAB, the storied French company declared bankruptcy purportedly due to quality and delivery issues surrounding Dalsa’s S35 CCD sensor. Another death in the family, from Sweden, is Ikonoskop’s A-cam dII, a tiny extruded box, originally C-mount, that was the digital answer to Aaton’s S16 A-minima. It fit the palm of your hand (with a big cut-out for your thumb) yet captured 1080p as uncompressed 12-bit RAW using Adobe’s CinemaDNG file format. (Ikonoskop were the first to record to CinemaDNG).

Although introduced circa 2008 and seen at every NAB since, Ikonoskop could never quite bring its bantam trailblazer to market, or for less than $10K. Meanwhile, the market moved on, as it always does, serving up cheaper alternatives, and Ikonoskop sought bankruptcy protection last July. I didn’t include A-cam dII in past camera round-ups because I chose to limit coverage to cameras with S35 sensors, which were breaking important new ground at the time.

CROWDSOURCING & DIY

But, as cell phone forefather Alexander Graham Bell once remarked, “When one door closes, another opens.” (True, he originated this line!) This last year has seen the unlikely rise of crowdfunding, namely Kickstarter, as an engine of camera development. Perhaps the best known example is Digital Bolex, whose inaugural D16 just happens to incorporate the same S16-sized Kodak CCD as the A-cam dII, as well as the same uncompressed 12-bit RAW to CinemaDNG recording.

Digital Bolex, who licensed the Bolex name for North American sales only, has no more to do with the classic Swiss firm than the design of their D16 has to do with the iconic spring-wound H-16 Rx. Announced at SXSW in 2012, its shape, which has been described as “ray gun,” embodies an aggressively retro attitude, including a crank and detachable pistol grip, and all but assumes you own a collection of vinyl too. Clearly the first digital motion picture camera conceived by Millennials and generated by today’s democratic start-up culture.

There’s no viewfinder really, and audio XLR inputs are on the traditional “operator side” of the camera. An internal battery powers the D16 for four hours (a 4-pin XLR next to the audio XLRs accepts external power), while an internal SDD, 256 or 512GB, undertakes recording. There are two CompactFlash slots, but at present they’re only for offloading the SDD. CinemaDNG files can also be downloaded via a USB 3.0 Micro-B connector.

Philip Bloom, an early adopter who took possession of one of the first batch of C-mount D16s in December, repeats like a punch line in his charming 40-min. video review that the D16 “is not a low-light camera.” Of the current 100, 200, and 400 ISO settings (800 is promised), he states flatly that 200 is optimal. Maximum frame rate at full resolution, 2K or HD, is 30 fps.

While the ill-fated A-cam dII offered HD-SDI, timecode, viewfinder, and a rock-solid build, the Digital Bolex team has brought their product to market for a third the price, namely, $3299 (256GB version), which meets their stated principle: “Must Not Be More Expensive Than a Top of the Line DSLR.”

It’s easy to poke fun at a camera in which function follows form (worse, pop styling), but the Digital Bolex team are clever and thinking outside the box. For example, they’re developing a set of 10mm, 18mm, and 38mm ultra-compact C-mount lenses with a fixed f/stop of 4 and no moving parts. At $300 each, lacking internal coatings to prevent flare, sharing a 40.5mm outer diameter, they invoke the simplicity of classic Switars. (They’re designed by Sadhvani Kish, who started as a lens designer for Cooke.) Exposure can be controlled with a variable ND with step-down ring, and a novel rail system in the camera body slides the lens in and out for focus, operated by the crank. A prototype three-lens turret takes this innovation to the next retro level.

Digital Bolex cites Silicon Valley entrepreneur Eric Ries and the “minimum viable product” concept touted in his 2011 book, The Lean Start Up, as inspiration for a product that intentionally doesn’t do everything, but pares down critical functions to achieve dogged simplicity at low cost. This example of the democratization of camera manufacture by way of the DIY ethos represents a potential seismic shift from the way video cameras have been created ever since inventor Vladimir Zworykin handed a working Kinescope to David Sarnoff of RCA. Ironically it also harkens back to an era of small shops designing and building early motion picture cameras a century ago.

Perhaps the beau idéal of DIY, funded not on a crowd but individual scale, is Black Betty. “Just two dudes,” self-described, in Boston cobbled together a Silicon Imaging SI-2K Mini Camera head bought used off eBay and an Apple Mac Mini to create an ergonomic digital incarnation of a 16mm camera. (Makes me want to put tape around the “magazine.”) It takes 16mm lenses and records 2K Cineform RAW to common SSDs. Best of all, there’s a simple start/stop button on the handgrip, that’s it.

Yet another crowdfunded camera project under sail, the 4K apertus° Axiom Alpha, promises, if built, a 4:3 S35 CMOS with global shutter and uncompressed 4K RAW output.

4K UPDATE

Speaking of 4K: a year later, how’s it doing? Momentum is snowballing. Don’t confuse 4K’s prospects with the 3D debacle four years ago, when the industry bet its resources on a supposed consumer hankering to wear dark glasses and watch overpriced 3D TVs. 4K simply brings my digital motion picture camera in line with my aging Canon 7D, which snaps images greater than 5K. Why can’t my digital motion picture camera do that, only 24 times a second?

Enter Gordon E. Moore. Each couple of years brings us faster silicon — more CPU cores, more powerful ASICs and FPGA’s, denser VSLIs, faster read-outs from CMOS imagers, lower power draws — which enable brawnier camera operating systems and ever more efficient codecs.

The upshot is that affordable 4K camcorders are invading the consumer market at the very time they’re popping up in our professional realm. (More below.) This exposes the obverse side of Digital Bolex’s “minimum viable product” coin. In the process of paring down, what are you giving up? For example, what kind of digital motion images will the D16s’s $3299 buy in a current DSLR?

MIRRORLESSNESS

This last question is salient in light of this year’s third notable development in digital motion picture cameras: mirrorless, interchangeable-lens still cameras that also capture 4K. Technically not DSLRs — no reflex mirror flips down for direct viewing — these new designs are variously called MILCs, for mirrorless interchangeable-lens camera (sounds vaguely pornographic to me), SLDs, for single-lens digital, and DSLMs, for digital single-lens mirrorless.

Whatever the label, a mirrorless, interchangeable-lens paradigm replaces a traditional optical viewing system with an electronic viewfinder and/or large LCD. Losing the mirror and reflex mechanism allows the body of the camera to collapse in size and drop ounces. With no mirror to take up space, lenses are mounted much closer to the sensor, which simplifies lens designs and improves optical performance. The resulting shallow flange focal distance permits cheap mechanical adapters for virtually any lens that covers the sensor: Nikon, Canon, Pentax, Voigtländer, Zelss, PL, the list goes on.

Two mass-market mirrorless cameras in particular are poised to make 4K inroads, one based on the Micro Four Thirds system favored by Panasonic, the other Sony’s E-Mount system.

Micro Four Thirds gave us Panasonic’s popular Lumix DMC-GH2 and -GH3 mirrorless cameras as well as Panasonic’s first large-sensor camcorder, the AG-AF100. In February Panasonic announced the 4K Lumix DMC-GH4 — $1700 for the body and $2000 for an optional DMW-YAGH Interface Unit with pro video connections – both of which I previously detailed in Filmmaker.

Using 8-bit 4:2:0 high profile H.264 compression, the GH4 internally records HD (200 Mbps intraframe), Ultra HD and 4K (both 100 Mbps, long-GOP) to turbocharged SDXC cards. Uncompressed 10-bit 4:2:2 Ultra HD and 4K can be output to a third party recorder via HDMI 2.0 or with four 3G-SDI cables (quad output) using the optional video adapter.

Since it arrived four years ago, Sony’s E-Mount has straddled still and motion cameras. On the motion side it has given us the FS100 and FS700, as well as economical large-sensor camcorders like the APS-C NEX-EA50 and full-frame NEX-VG900 (each about $3300). This underscores the key difference between E-Mount and Micro Four Thirds: sensor size. While an E-Mount sensor can be either APS-C (same as S35) or twice that size, full-frame, an MFT sensor falls about halfway between S35 and S16.

What’s more, the GH4 achieves its Ultra HD or 4K image by “windowing” a smaller center section of its sensor. In the case of 4K, this area equals 4096 x 2160 pixels. (Canon’s 1DC DSLR does the same.) The GH4’s cropped 4K scan is barely larger than a S16 frame, yielding S16-like depth of field, which can be terribly advantageous in hand-held documentary production.

At NAB Sony has announced the Alpha a7S – an Ultra HD version of its E-mount, full-frame Alpha a7R, the big buzz in photographic circles at the moment.

What sets the a7S apart from the a7R is pixel count. Where the a7R ($2300) boasts a whopping 36.4 megapixels, the a7S introduces a new 12 Mpixel full-frame Ultra HD sensor with only a third of the a7R’s pixels – which means its pixels can be three times larger! This translates to low noise, high dynamic range, and astounding, see-in-the-dark sensitivity: an ISO range of 200-102,400 for Ultra HD. Is there a faster camera out there, 4K or otherwise? (Canon’s 1DC tops out at 25,600 in 4K mode.) It also means that, unlike an a7R, there’s an Optical Low Pass Filter to defeat aliasing and high-speed readout to defeat rolling shutter.

Internally the a7X records HD using XAVC S, Sony’s high level H.264 codec, at 50Mbps (8-bit 4:2:0 long-GOP) to SDXC and Memory Stick cards. Ultra HD, not recorded internally, is output 8-bit 4:2:2 via HDMI 2.0 and must be recorded using a third-party recorder. Maximum frame rate is 30 fps. Professional features include S-Log2 gamma, picture profiles, timecode/user bit support, and optional XLR audio inputs. When shooting 720p, frame rates up to 120 fps are possible.

At NAB you’ll find an a7S featured at the Atomos booth. I’m pretty sure the just-announced Ninja Blade, hardly larger than its 2.5-inch SSD media, will be on the receiving end, even though it’s designed to capture uncompressed HD to 10-bit 4:4:2 ProRes or DNxHD. An Ultra HD version of Ninja Blade perhaps?

In comparison to the GH4, the full-frame Ultra HD image of the a7S – no windowing — produces shallow depth of field and more than twice the horizontal angle-of-view for any given focal length. Both camera bodies are remarkably light – 19.8 oz. for GH4, 14.3 oz. for a7S – ideal for gyro-stabilized hand-held systems like Freefly’s MOVI M5, with its 5-pound maximum payload, and compact aerial drones. When it comes to drones in particular, however, twice the horizontal angle-of-view confers a distinct advantage on the a7S.

Except for a blue “S,” the a7S looks like exactly like the a7R. It has the same startlingly clear 2.4-million dot OLED viewfinder (GH4 has similar), which would pass for optical if not for superimposed symbols and characters. And I think it will be priced to compete. But even if it were to retail $1000 more than the a7R — to stay competitive with the GH4, I don’t think it can — it would still cost no more than a Digital Bolex. How’s that notion of minimum viable product looking now?

16MM REDUX

The smaller sensor areas of the Digital Bolex and windowed 4K in the GH4 represent a fourth trend this year: a return to the classic look of 16mm. Those who shoot documentaries or fast-moving subjects hand-held, where greater depth of field is a godsend, as well as those who own 16mm and S16 glass are paying particular attention to this development.

At last year’s NAB, Blackmagic Design introduced its mirrorless Micro Four Thirds Pocket Cinema Camera with a S16-sized sensor. Hardly larger than an iPhone, it records to an internal SD card either 1920 x 1080 RAW to lightly compressed 12-bit CinemaDNG, or HD to 10-bit ProRes HQ. Best of all, it retails for under $1000. The perfect RAW crash cam?

In December Sony released a free firmware upgrade (Version 3.0) for the F5 and F55 that adds “2K Center Scan” windowing for use with S16 lenses. Sony will soon bundle a third-party B4 mount adapter with the F5 and F55 to permit use of 2/3-in. ENG zooms in 2K Center Scan mode, with a mere 2/3-stop light loss. Available recording formats are XAVC HD or 2K, HDCAM SR, and 2K RAW.

Of course RED invented 2K windowing for RAW capture with RED ONE in 2007. Since RED ONE’s 4K topped out at 30 fps, windowing at that time enabled 120 fps whenever needed. Epic bumped the windowed frame rate to 300 fps. So even though it has been possible to shoot entire projects with S16 lenses on RED cameras since the beginning, the ergonomics beneficial to long stretches of hand-held technique is not what RED is known for. And those drawn to RED’s 4K and 5K sensors were, and are, mainly interested in large-sensor cinematography.

It’s also worth noting, for sake of context, that a 2/3-in. sensor is roughly equivalent to standard 16mm in terms of image size. Put another way, the two formats match when it comes to horizontal angle-of-view. But it also goes without saying that the highly compressed, over-sharpened, shallow-bit-depth, color-subsampled look of ENG video is exactly what we’re trying to escape from when we shoot RAW or use Log gammas with today’s digital motion picture cameras.

I mentioned consumer 4K (actually Ultra HD) camcorders: Google the Sony FDR-AX100 or FDR-AX1. Or GoPro HERO3+ Black Edition. Or pro version of the Sony FDR-AX1 called PXW-Z100, which I profiled in Filmmaker last September. While not S16 exactly, they share S16’s deep focus aesthetic.

Looking like a slightly swollen member of Sony’s current Handycam line-up, the Z100 with a street price of $5500 “would seem to do for 4K what Sony’s epochal HVR-Z1 did for HD almost a decade ago…” The Z100 impressively records 4K and Ultra HD as 10-bit, 4:2:2, intraframe XAVC, up to 60p, using new, fast solid-state media called XQD, developed by Sony, Nikon, and SanDisk to replace the 16-year-old CompactFlash.

These consumer camcorders are advance troops for what the industry hopes will grow into a home invasion of 4K. But the Z100 with its almost ½-in. sensor demonstrates an interesting roadblock. Smaller 4K sensors pack smaller pixels and smaller pixels are less sensitive. They shrink as targets and fewer photons hit them. The only solution is to boost gain at the cost of noise. Which is why the Z100 is a poor performer in low light, reminiscent of the old Sony V1.

Perhaps pro 4K sensors should stick to size S16 or larger.

REINVENTION OF SHOULDER CAMS

Two heads are better than one, no? Last year’s balsacam becomes this year’s VariCam as Panasonic at NAB bounces back with a new system that manages to be both 2/3-in. and S35.

No, not interchangeable sensors, a never-realized goal of early digital cinema cameras… Panasonic instead introduces a 2/3-in. head for HD and a S35 head for 4K, which use the same recording module. The recording module docks to either of the identical cameras by V-mount. It can also be tethered by cable for remote use. Like an Alexa and Alexa M but in one package.

The S35 PL-mount head is called VariCam 35 (no global shutter). The 2/3-in. three-chip B4-mount head is called VariCam HS for high speed. If you don’t look too closely, you might mistake them for a Sony F5 or F55, or even an Alexa. (Hint: Alexa is always the one with a built-in shoulder pad arch, attachment rosettes and front holes for 15mm rods. ARRI, you see, knows a thing or two about hand-holding.)

On the operator side you’ll notice VariCam’s small rectangular user interface display screen — in the style of Alexa’s assistant-side U.I. with its convention of three control buttons top and bottom, homepage camera status in big characters, and monochrome look. The F5 and F55 moved their version of Alexa’s U.I. to the operator side, directly below the handle. Panasonic’s version is also on the operator side, but located on the recorder. In other words, these new VariCam heads must be used with the VariCam recorder module, which also contains the video outputs — quite unlike F5 and F55 cameras, which incorporate video outputs and can stand on their own. (Notably, VariCam’s U.I. is detachable as a module for remote control.)

Panasonic says the VariCam recorder module is capable of variable 4K frame rates, ramped up to 120 fps. This would involve one their H.264 codecs, likely AVC-Intra Class 100. For 1080p, variable-speed frame rates climb to 240 fps. Higher AVC-Intra and AVC-Ultra bit rates achieve 10-bit 4:2:2 and 12-bit 4:4:4, coupled with a new Log gamma to preserve dynamic range.

A fast new P2 card called expressP2 debuts at NAB, which holds over two hours of 4K at 24 fps. VariCam’s recorder provides two expressP2 card slots for 4K and high frame rate recording, as well as two microP2 slots (same size as SD) for HD and 2K. VariCam’s recorder also outputs 4K and Ultra HD via four 3G-SDI cables (quad output) and RAW via two 3G-SDI cables. This indicates the need for a third party recorder to capture RAW.

I’m particularly impressed with VariCam’s OLED viewfinder design and can’t wait to try it. VariCam availability, per Panasonic, is this fall and price is to be determined. If the price is right, this third-generation VariCam system could be a big hit.

Add a baseplate with rods and shoulder pad by Movcam, Vocas, or ARRI to a VariCam 35 and it joins the F5 and F55, and Alexa before them, in defining today’s shoulder-mounted large-sensor camera. This drive towards sensible ergonomics includes Fujinon’s compact, servo-driven Cabrio zooms – 14-35mm, 19-90mm, 85-300mm — with rocker-switch control (think inflated ENG lenses) and a similar new compact zoom, CINE-SERVO 17-120mm, which Canon will unveil at NAB.

Sony, in turn, is taking modularity in a novel direction at NAB with its new “build-up kit” for F5 and F55. Essentially an L-shaped cradle that wraps around the camera body, the build-up kit converts the F 5 and F55 into an ENG camcorder equivalent, something like an F800. Sony says it takes five minutes to attach.

The build-up kit adds a camera base with shoulder pad, 15mm rods, ARRI-style rosettes, a new handle with mic holder and viewfinder mount, and a rear interface section that shifts XLR inputs to the back. Audio controls are moved from submenus to actual physical knobs on the operator side. There’s also a module next to the lens mount with rows of buttons to control frequent settings like gain/ISO, white balance, and shutter speed, including user assignable buttons. Slots at the camera’s rear accept wireless mic receivers. Sony says the build-up kit is available this fall, price to be determined.

Ergonomics pacesetter ARRI hasn’t slacked off either. At NAB ARRI is introducing its latest belle, Amira, what it calls “the new documentary-style camera” designed to boot up while being picked up. Or as ARRI’s website puts it: “Pick Up > Shoot.”

In a sense, Amira is Alexa on a crash diet. Same 16:9 sensor, same color science inside, same light charcoal spatter finish outside. But the body sans viewfinder has dropped serious weight, from Alexa’s 14 lbs. to about 9 lbs. (For comparison, the F55 body weighs 5 lbs.). Power use, from 90W to 50W. And price has dropped too, from Alexa’s base $75K to $40K for an “entry point” Amira with viewfinder, limited to Rec 709 ProRes 422 and 100 fps.

ARRI will tier Amira models in terms of functionality, with a pricier version around $45K that adds Log C, ProRes HQ at 200 fps and cached pre-record, and a “premium” version for around $50K that adds 2K and ProRes 4444 up to 200 fps, plus custom 3D LUTs. These are base prices; choice of lens mount (PL, EF, B4), battery mount, batteries, baseplate assemblies and other accessories can add another $10K.

Amira’s costs are not for everyone. Others will balk at the lack of a RAW option. (Didn’t seem to hurt the look of Dallas Buyers Club, reportedly shot in ProRes 4444 with Alexa.)

I spent time with an Amira prototype on display at Sundance in January. The build of this camera is ARRI rock solid. Machining second to none. Adjustability is unsurpassed. You simply believe in it. With a shoulder that’s hefted decades of Aatons, SRs, CP-16s, and Betacams, I can report that Amira achieves a deliciously seductive balance – if the lens isn’t competing in weight. The 28mm Zeiss Ultra Prime and lightweight ARRI clip-on matte box I tested were perfect for hand-holding. I’m not so sure how 6.4 pounds of a cantilevered Fujinon Cabrio or Canon CINE-SERVO zoom would feel after a half-hour, though.

To facilitate single-operator run-and-gun work, Amira’s controls have been brought around to the operator side like F5, F55, and VariCam. A novel LCD monitor hinged to the brilliantly sharp OLED viewfinder doubles as the main 6-button user interface to access camera menus.

Amira is pioneering use of a new media standard, CFast 2.0, derived from CompactFlash and intended for pro video recording. The Sandisk Extreme Pro 120GB card I tested is $1200 at B&H. A 60GB version is about half that much.

While you can fantasize about an Amira that’s lighter and cheaper, you gotta love a camera that has a real bubble level built in!

RISE OF PLATFORMS

Amira and VariCam 35 and HS turn out to be exceptions to this year’s fifth emerging trend, which is to not introduce a new camera, but rather introduce significant performance upgrades through firmware releases and board swaps, a strategy borrowed from ARRI’s and RED’s playbook. RED, for instance, has produced few camera models but, along the way, incrementally improved the performance of each one. If you bought an EPIC anytime since its introduction in 2011, you can get in line to swap out the original MYSTERIUM-X sensor for a new, larger DRAGON 6K, which the influential website DxO Mark just rated as superior to Nikon’s D800E and Sony’s a7R.

ARRI and RED, in other words, build camera platforms. In so doing, they tap into something fundamental. If a camera is built to last, as opposed to being built to be replaced, the owner feels better about the investment, even, or especially, if it is substantial. The owner also feels better about his or her investment in lenses and camera accessories, which can rival the camera in cost. And not least, the owner feels better about the investment of time and energy it takes to master a particular camera system. Pride of ownership builds brand loyalty like nothing else. Except perhaps free firmware updates that enable fun new features.

Perhaps this is why Canon and Sony have joined the club. Canon are bringing no new digital cinema cameras to showcase at NAB. Instead they will demonstrate the latest firmware updates to their Cinema EOS line of cameras. In December a free user-installed firmware update for the C300 added 15 features including push auto-iris and one-push momentary (not continuous) auto focus for EF lenses, continuous autofocus and auto-iris for Canon EF STM (stepper motor) lenses, movable 2x magnification for focusing, a new wide-dynamic-range gamma with 800% headroom for highlights, a new 1440 x 1080 35 Mbps mode for ENG, and a hike in ISO to 80,000.

I found the one-push momentary autofocus to be of little use in a feature documentary I shot hand-held last December. It is contrast-based and not remotely fast enough for the quicksilver situations I faced. By February Canon had announced a $500 upgrade to the C100 that adds dual-pixel autofocus (a/k/a phase detection) identical to that introduced last summer in the Canon EOS 70D. With contrast detection and dual pixel working in tandem, the C100’s autofocus is now perky and accurate, if determinedly center-weighted. Canon did not announce, but one can assume, a similar C300 upgrade in the near future. A trip to a Canon service center is required.

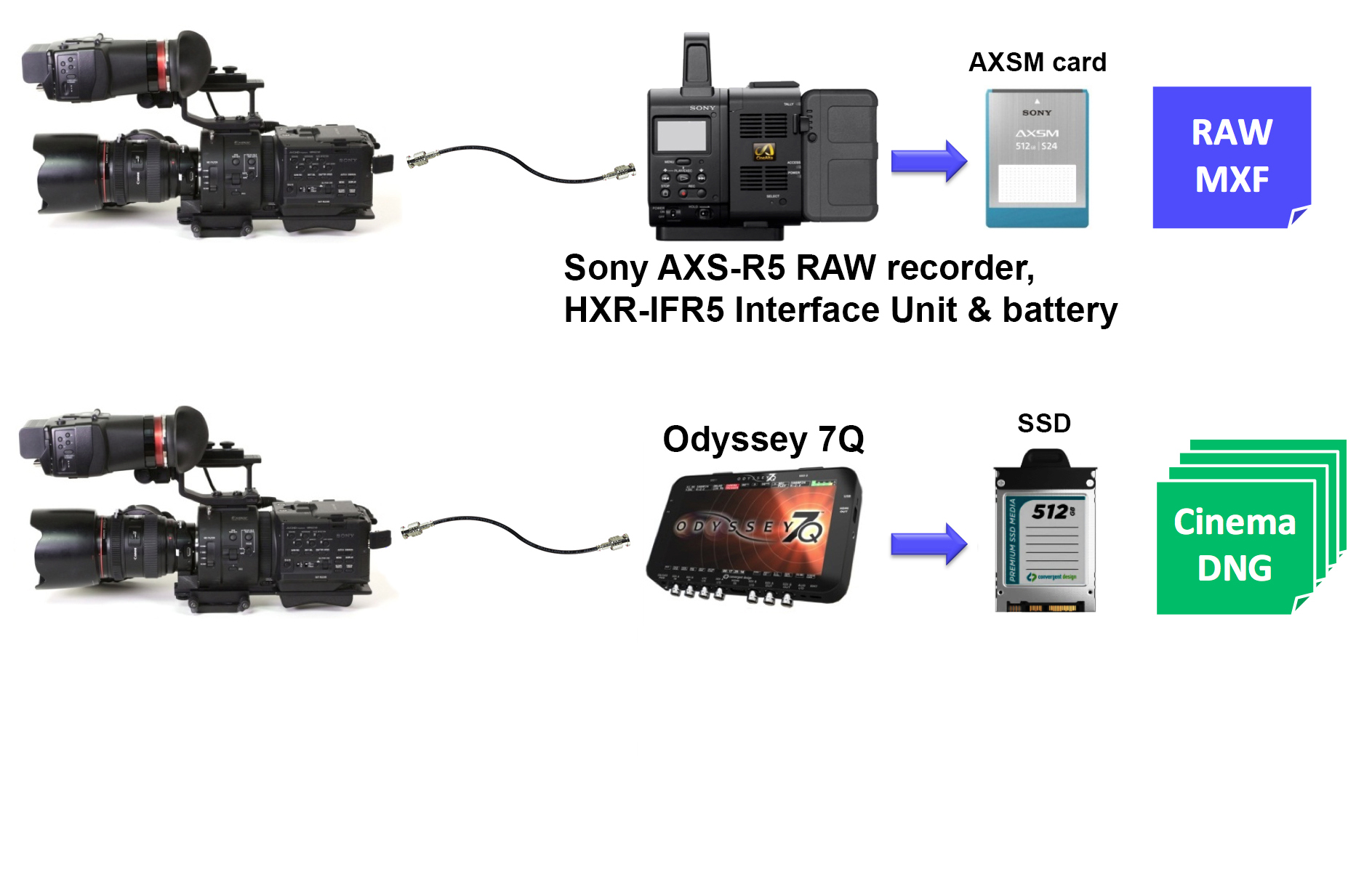

Sony is following a similar path. They announced in June a Version 3.0 firmware upgrade for the NEX-FS700 that adds 12-bit RAW recording when using Sony’s AXS-R5 RAW recorder (same one the F5 and F55 use). With only a single 3G-SDI cable to connect FS700 to R5 recorder, 2K RAW can be recorded up to 240 fps, and 4K RAW up to 60 fps. An internal buffer even enables a four-second burst of 4K RAW at 120 fps. Also included in Version 3.0 firmware is the S-Log2 gamma found in the F5 and F55. This upgrade requires a trip to a Sony service center and a $400 labor charge, so in September Sony introduced an “R” version of the FS700 with 3.0 already installed.

Enabling a $7700 camcorder to show what it can really do — high-frame-rate RAW — has opened new doors. Anyone who has tried to order a Convergent Design Odyssey 7Q monitor/SSD-based RAW recorder since they arrived in October knows they’re virtually sold out. Much of this demand is tied to the FS700R’s new 2K and 4K (4096 x 2160) capabilities. Therein lies a back story.

Sony’s RAW output is not conventional. To send 4K RAW at 60 fps down a single cable, Sony developed some deft signal compression technology, intended to advantage to its own RAW recorder, the R5. In a spate of behind-the-scenes diplomacy last year, however, Sony agreed, after much internal discussion, to provide Convergent Design with an SDK (software development kit) to permit Odyssey 7Q to also capture Sony 12-bit RAW.

At the outset FS700R’s third-party recording was limited to 2K RAW up to 240 fps. Convergent Design’s March 19th firmware update has just raised this bar: 4K RAW up to 60 fps. Also new with this update is “4K2HD,” in which the FS700R’s 4K RAW output, up to 30 fps, is deBayered on the fly and recorded as ProRes 422 HQ. Both REC709 and S-Log2 are supported. With this latter choice, you get a super-sampled image with extended dynamic range for grading, instantly ready to view. Sweet!

Convergent Design’s March 19th firmware update to its Odyssey 7Q recording platform also adds support for Canon’s C500, including Ultra HD RAW recording up to 60 fps and recording 12-bit 2K/1080p RGB as DPX files up to 30 fps. Uncompressed 12-bit RGB from the C500 has to be seen to be believed, it’s that good. Can 4K ProRes be far behind?

Sony’s F5 and F55 camera platform has not been neglected either. December brought firmware Version 3.0 with 28 new features, including user LUTs, a new S-Gamut3 color gamut, new S-Log3 with 1300% dynamic range, internal Ultra HD recording to XAVC in the F55, Slow & Quick motion for 4K and Ultra HD XAVC, auto-iris for B4 lenses with an adapter, and 2K Center Scan mode for S16 lenses.

This last feature, described above in “16mm REDUX,” is a breakthrough, turning both F5 and F55 into two cameras in one. NBC Sports is reportedly crazy about it, since S16 deep focus facilitates tracking fast action. The last camera to pull off this duality, by the way, was the mid-1950’s Éclair 16/35 Caméflex, which set in motion nothing less than the French New Wave.

Firmware Version 4.0 for the F5 and F55, released April 4, adds user generated 3D LUT’s, access to menus from the user interface display, extensive menu customization, viewfinder markers in seven colors, start/stop with ENG zooms using the RET button, and, notably, implementation (F55 only) of last fall’s HDMI 2.0 standard, which supports 4K and Ultra HD to 60 fps as well as Rec. 2020 color space.

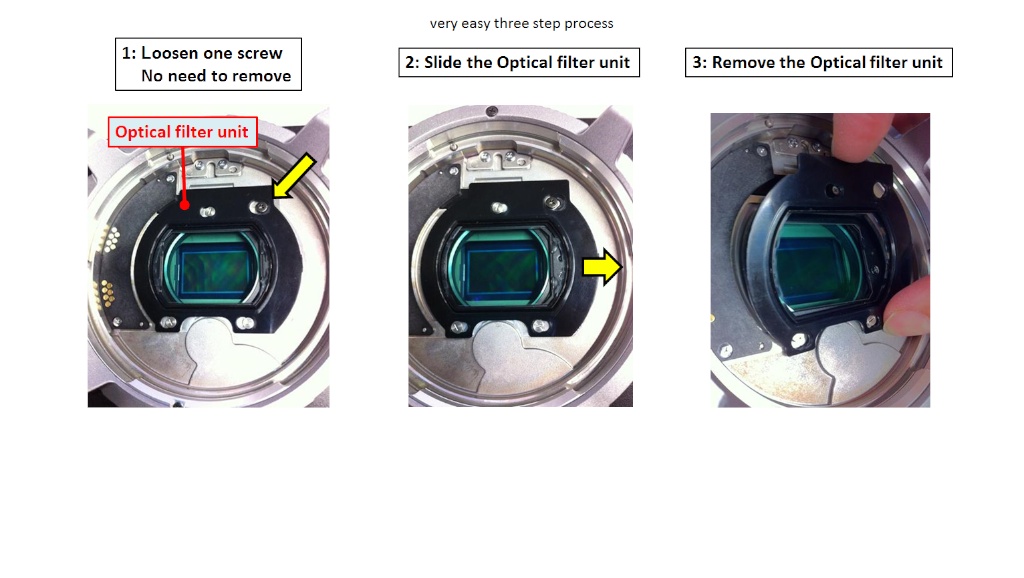

Sony’s platform upgrades are not just software. Exhibit A is the “build up kit” described above that reconfigures an F5 or F55 into an ENG camcorder. In September Sony announced an optional 2K optical low-pass filter, CBK-55F2K, that improves aliasing when shooting 2K with the full F5 or F55 sensor. An interchangeable OLPF is a first for any camera. Changing it takes a tiny screwdriver and perhaps five minutes of the user’s time. Sony even hinted a creative outcome of “softer, more organic” images when using the 2K OLPF to shoot 4K. Sort of like a Tiffen Satin filter, but behind the lens.

In the run-up to NAB, Sony floated the news that ProRes and DNxHD were coming the F5 and F55 – the first time a Sony camera would incorporate third-party codecs. This would require a new compression board. There seems to be discussion about whether or not this includes ProRes 4444, the codec that fueled Alexa’s conquest of episodic TV.

OTHER HORIZONS

How can I neglect to mention Blackmagic Design’s Production Camera 4K? Introduced a year ago at NAB (down payments were taken), the Production Camera 4K just started shipping a month ago as of this writing. Delays were due in part to problems with the first batch of production sensors. But 4K RAW CinemaDNG has yet to be implemented. More than a work-in-progress, less than promised, the 4K Cinema Camera has had, to date, no practical impact. Will it?

Nor did I mention GoPros, which, like RED, have engendered a testosterone-inflected subculture of cool. Like Apple, an ecosystem of accessories too. Every teen craves one. No 4K camera is more playful. Every light drone accommodates a GoPro HERO3+ Black Edition. But I need a Rosetta Stone to decipher the menus. No thanks.

Action cams, in any case, are a universe unto themselves. DP extraordinaire Anthony Dod Mantle used Indiecam’s recent 12-bit 2K RAW micro camera with global shutter to shoot scenes in Ron Howard’s kinetic Rush. Codex gets into the same game at NAB with their new Action CAM, substituting a 2/3-inch CCD for CMOS, HD for 2K, and halving Indiecam’s length – a result the size of an ice cube. Panasonic just announced the HX-A500, the “world’s first 4K/30p Wearable Camera,” relying on Wi-Fi and NFC (near field communication) to connect to your smartphone. Will it out-GoPro the GoPro?

I have not mentioned 3D. Reports of its death are exaggerated. 4K is the key that will unlock consumer lust for 3D. HD screens simply did not provide the kick 3D needed. 4K screens, with four times the pixels, do. I experienced this first-hand at NAB last year. The difference was dramatic. Don’t give up on 3D camera systems yet.

I mentioned crowdfunding as a left-field source of fanciful digital cinema camera designs, but there is another one, right under our noses. China, home to the biggest cinema audience on the planet, can land a rover on the Moon yet can’t create a new digital camera? In fact the Chinese market is snapping up 4K TV sets faster than any other, according to the trades. Why not fashion a 4K camera? Or a 6K camera? Why not indeed? See here and here.

There’s also 8K. Sony at NAB will be showing the results of an 8K RAW shoot with the F65.

But hey, I have to save something to write about next year!