Back to selection

Back to selection

Down in the Boondocs: The NYFF’s Go-To Films (I)

Timbuktu: (l-r) Toulou Kiki, Layla Walet Mohamed, Abel Jafri, unknown

Timbuktu: (l-r) Toulou Kiki, Layla Walet Mohamed, Abel Jafri, unknown The expansive New York Film Festival is no longer the greatest-hits affair of three decades back when it was built around 20-25 titles, a majority of which were what had been on display at the previous Cannes. The arrangement was a gift and a curse: manageable, for both journalists and completists, but limited. I remember what a production it was when the fest dared to add a lowbrow Hong Kong movie by one Jackie Chan.

Now there are lots and lots of strands, which cover a variety of genres and niche audiences — followers of the avant-garde and new technologies, for instance — some of it made possible by the range of seating in the new theaters. Sections I find particularly inspired are the Retrospective, this year the work of Joseph Mankiewicz, and the whole of Revivals, with its diverse roster of discoveries and restorations. Continuing as before are the invaluable director’s talks, which are solid one-on-ones with informed programmers that certainly beat the painful post-screening Q&As.

There are some misguided decisions, some missed opportunities. Lisandro Alonso is one of my favorite directors, but inviting him as the second filmmaker-in-residence during this busy period seems an unnecessary distraction. Is the NYFF becoming a little ravenous, competing with Toronto? Audiences have their heads stuffed with options, but last I heard, visiting filmmakers were still complaining that there was no suitable, convenient place for them to meet and interact.

These are minor concerns. What stings most, especially in 2014, is the near-total exclusion of docs from the Main Slate. (Nick Broomfield’s Tales of the Grim Sleeper was until a few days ago the exception, until the very-last-minute addition of the multifaceted Laura Poitras’s CITIZENFOUR, the account by one of the world’s finest documentarians of becoming acquainted with Edward Snowden.) They are now ensconced in a block entitled Spotlight on Documentary and, to my mind, relegated to a lower grade. In the interest of space or time or projection overload, many journalists will end up excising the section from coverage in favor of the one that gets the fanfare (and the most screenings).

According to the fest’s website, “It’s a commonplace to think of documentary as an add-on to fiction, something extra, and of course nothing could be further from the truth: cinema started with documentary, and it will always be at the core of the art form.” Yet the FSLC has side-barred the docs, especially jarring because this is arguably the most consistently excellent group of films in the entire event. In my litany of must-sees from the first half of the festival below, three are docs; six, Main Slaters. If you check the schedules, there is some quantitative merit to the assertion.

As most of us well know, in the earliest days of filmmaking, the brothers Lumiere and Georges Melies represented the extremes of representation: the former, the realism that would become documentary; the latter, theatrical artifice that laid the groundwork for generic fantasy. In the past decade and a half, the two traditions have increasingly overlapped. Programmers have had to adapt to the transformation; for example, where do you put hybrids?

Thankfully, the subjective split has gone out of fashion — but, strangely enough, it has managed to resurface here. Given the heavy francophone load this year, you could call it a la recherché du temps perdu. You might compare the Spotlight on Documentary to Cannes’ Un Certain Regard, what Richard Corliss once called the “thank-you-for-coming” section. It’s terrific to have more docs available, but I don’t understand why the organizers didn’t just enlarge the Main Slate and give the docs the due they’ve been getting ever since Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 won the official competition at Cannes a decade ago. How about a double slate, visualized like the two tablets of the Ten Commandments? If someone feels the need to make a distinction, they could put fiction on the “Thou shalt have no other gods before me” side and docs to the right, where you’d expect to find “Thou shalt not kill.” Or a Main Slate and a Mainer Slate. What do I know?

More than a century after Melies and the Brothers Lumiere displayed their wares, another variable comes into play: geography. These movie pioneers were French, the former from magic shows, the latter from factory ownership. In the US the Lumiere tradition of naturalism was the one that took off, via the likes of Porter and Griffith. The three docs reviewed further down are by American directors; in fact, 13 of the 15 total selections in the Spotlight on Documentaries are by Americans. (Broomfield is British, his film a US-UK coproduction) Announced after the Main Slate, could these have been assembled in a rush? Are potential ticket sales a factor, even with all the theatrical options?

The seemingly full-gallic sourcing of main-slate movies versus the strong American bent of the docs smacks of an imbalance a bit too pronounced. On top of that, all but one of the films added as Special Events are French. Perhaps I’m being twisted and glib, but it reminds me of another bizarre, much more serious time when the opposite took place, the differences were foregrounded: Bush 43 forming the notorious Coalition of the Willing, when zealots here went overboard, pouring out fine French wines and rechristening one of our favorite unhealthful snacks freedom fries.

Come on, it’s a big world out there. In all of the sections, only one film from Asia — a Korean film with a Japanese man and Korean woman speaking in English? Let me be perfectly clear: The French are as cinephilic as the cliché. It’s no accident that the auteur theory took root there, as has, in fact, most film theory. We all know how many French critics have become directors. On a personal note, I did my time in Paris in the ‘70s, a grand time to watch movies in 35mm in theaters. It was a goldmine. I am not slamming French films or French filmmakers. The FSLC has programs year-round that honor directors from other parts of the world, but somehow, relatively few of the works made it into the NYFF. The scales are out of alignment.

The three American fiction features in the Main Slate that garner the most attention are studio fare, clumped, as is the norm in large festivals, like big department stores that anchor shopping malls on both ends (opening and closing nights) and in the middle (centerpiece). To be sure, there are a few good American indies scattered throughout. Their domestic origin is nothing compared to the docs, of course. We may not be the best at, say, magical realism or surrealism, but is our destined forte a naturalism dependent more on brilliant recording and editing than on a broader imaginative sensibility that kicks in from start to finish, one that determines what shall be recorded?

From the films screening until just after midpoint, here are, in no particular order, nine titles in total from the Main Strand and the Spotlight on Documentary that are my very special recommendations on what is not to be missed over the next 10 days. On October 6 I’ll note what I consider the best among the films in those same strands that screen the final week. My take so far is that the word after it’s all over will be, “It was a very good year.”

MAIN SLATE

Timbuktu (Abderrahmane Sissako, France/Mauritania)

The jihadist takeover of northern Mali in 2012 becomes, in the hands of the great humanist Sissako (Bamako), a battle between bland dogma enforced by unwelcome hypocrites in SUVs with machine guns and the colorful imagination of the local Muslim cultures that enliven the vast desert expanse. The red mud walls and rooftops (never a master shot) of a surrogate for the actual Timbuktu provide a striking complementary backdrop.

Several local characters recur throughout the film, their dispersal — as if they were gliding through — providing momentum to a narrative that might be otherwise weighed down by so much inhuman ideological bastardization. Each is part of a different subplot that pits them against the roaming bands of religious police whose ideas of serious violation of shariah law are playing music, singing, dancing, playing sports, just milling about, and, for females, exposed face and hands. (The roaming squads from ISIS share common roots.)

The most rebellious and vociferous are the women, including a chanteuse who stoically endures painful lashing, the idiot savant who ostentatiously flaunts her bright outfits and gaudy jewelry, and a beautiful wife and mother, the pillar of a family of Tuareg nomads who live in a bright isolated tent and who stands up to an arrogant, overly personal jihadist officer.

The wife, Satima (Toulou Kiki), plays only a secondary role in the film’s major plotline, in which her mellow, guitar-playing husband Kidane (Ibrahim Ahmed), a cattle and goat herder, comes up against a local fisherman over the latter’s killing his prize cow when it wanders into his nets. Sissako does not lose sight of the complexity of the social fabric: strife between sedentary and nomadic tribes is entrenched in sub-Saharan societies. The quarrel ends with an accidental homicide.

With jihadists upholding The Law, the story moves in a particular direction, which the director manages to shape so that a morally reprehensible judgment is transformed into cinematic perfection. In this, as in other extreme long shots of violent acts, he is well served by DP Sofiane El Fani, who captures the desert’s peculiar emptiness all the way through with brilliant use of widescreen.

Timbuktu conveys both an overall haunting feeling and occasional glimpses of human warmth and dignity.

Eden (Mia Hansen-Løve, France)

Arms wave high in the air inside the crowded clubs; colored lights and the fog of cigarette smoke add to the ecstatic mood set by the mostly ebullient techno music. Hansen-Løve (Goodbye First Love) surveys the scene from a distance with slow pans and few cuts. Those shots are not super dramatic: she does not want to detract from the real subject of the film, the DJ himself. Paul (an exceptional Felix de Givry), though he may bounce up and down while mixing and is a well-regarded specialist in garage music, is something of a cipher — a handsome, androgynous, and easygoing blank who is reciprocally attracted to neurotic and complicated women. Even his close male friends walk a bit on the dark side.

The director observes him over a 20-year span, beginning in 1992, tracking his attempts to maintain a persona and professional style against the encroachment of time. He subtly endures highs and lows that could be seen as slight echoes of the dance songs he is so adept at synthesizing. But he is able to keep a lid on his mood swings with cocaine, a frenzied professional night life, and non-stop ephemeral affairs. Among his pals are the two guys who became Daft Punk. Paul’s is the story of a fellow who didn’t quite make it. For one thing, garage went out of favor; the public is fickle.

Hansen-Løve wrote the screenplay with her brother, Sven, a former DJ. His intimate knowledge of the character and the scene, in conjunction with her precise, unhurried method of filmmaking, makes for an amazingly poignant, affective work. With such deliberate pacing, by the time Paul is able to emote, by the time he has the ability to view his life from a slight remove, we can be there with him when he reveals his naked soul.

When you give your life to the arts, especially in the form of a business, it is only a matter of time before the stripping away of youthful illusions commences. But Hansen-Løve films this world with great affection and respect. To her credit, she does not make the multiple girlfriends (including Greta Gerwig’s expat) two-dimensional constructs whose dilemmas are necessarily bound up with Paul. Each has her own conflicts, her own ups and downs.

The Wonders (Alice Rohrwacher, Italy/Switzerland/Germany)

Rohrwacher (Corpo Celeste) attaches a multivalent title to her most recent excursion into tactile textures and empathy for outsiders. For one, it refers to a kitschy Italian talent-show-cum-reality-program (Il Paese delle Meraviglie) intended to exoticize the rural Tuscan peasantry, in part by linking their daily grind with a fictionalized Etruscan past. Condescending it may be, but desperate locals are counting on tourism generated by the publicity to help make ends meet.

The sad-eyed, 12-year-old protagonist Gelsomina, or Gelso (a superb, restrained Alexandra Lungo) — the subject of this coming-of-age story — and her siblings are seduced by what they consider the glamour of the lights and the overdone presenter, Milly Catena, played to the hilt as a fairy godmother by Monica Bellucci. For these isolated youths, the whole production is a wonder. It should be noted that Gelso’s folks are not typical farm folk: they are former student activists trying, mostly in vain, to construct a tiny utopia, living a natural life and earning money by selling honey from their resident bees.

The title also points to the surreal touch Gelso’s obsessive father, bearded German Wolfgang (Sam Louwyk), tries to add to the homestead to spice up what might otherwise become a dreary life for his kids. His most recent acquisition, with the last of the household money and repossession looming over their belongings, is a camel, but the impressionable kids delight more in the trappings of the TV spectacle. Their mother (played by the filmmaker’s older sister, Alba Rohrwacher, to me slightly miscast) surpasses the threshold of tolerance.

Yet another wonder appears once a young, melancholy German delinquent boy, Martin (Luis Hulica Logrono), possibly mute, begins serving alternate detention time by working on the farm. Martin and Gelso form an odd bond, one that has at least for her an unconscious sexual charge. He is more ambiguous: he is phobic about being touched, and his wardrobe suggests that he may have worked as a hustler back home. Their communication is necessarily silent, but she, unlike the others, gets him. Their wonder is an unscripted act during the live tv broadcast: he performs his signature whistle, while two bees crawl slowly across her face. That’s it. But it’s enough to shock both cast and crew and the local agrarians. With that the two not only say “fuck you” to the arrogant interlopers but turn the negative status of marginals on its head.

Although reserved, Gelso has a strong presence. Oddly enough, she and the extroverted Milly show a mutual affinity, the kinship of loners. Her Achilles heel is the tight but odd relationship she has with her father, who has become fiercely organic and militantly anti-insecticide. In one powerful extended sequence, following a costly laboratory accident she has precipitated, she pushes everything out of her mind and allows her whole sense of self to pivot on the man’s response. Did I mention tight?

La Sapienza (Eugène Green, France/Italy)

Cinema has been likened to a number of other art forms, but few filmmakers have ventured as far as the Russians Eisenstein and Pudovkin in elaborating and theorizing upon its similarity to architecture. Their comparisons were by and large in the area of structure, equating the progressive change in size of spaces to montage.

In La Sapienza, Green (The Portuguese Nun) goes a step further. With the religious work of the 17th-century Swiss-Italian architect Francesco Borromini as a touchstone, he finds in his baroque facades and interiors echoes of his characters’ aspirations and limitations. The undulation presents an openness that does not exist in more symmetrical styles; light becomes more accessible. Green mines the metaphoric implications of this distinct manner of design, one that lends itself to meditation on perpetual motion, both figuratively and literally. It gives a special emphasis to empty space itself.

Green has melded the world of stone with that of the spirit, which in fact the former was intended to represent in the first place. Early in the film a meeting between two couples that could have only been preordained takes place on Lake Maggiore in the Swiss town of Stresa, near Ticino, the birthplace of Borromini. Alexandre (Fabrizio Rongione) is an architect frustrated by clients messing around with his urban designs, so he has returned to his earlier research on the man and his work. Accompanying him is his wife, Alienor (Christelle Prot Landman), who works with behaviorally disadvantaged children.

The duo encounters two much younger siblings, who complement them almost congruently. Goffredo (Ludovico Succio) is a 17-year-old future student of architecture, as idealistic as Alexandre is cynical. His little sister, Lavinia (Arianna Nastro), has just suffered a dizzy spell, an ongoing problem, and the visitors go to help. The original plan was for Alexandre and Alienor to continue on to Turin and Rome, other cities with Borromini masterworks. Alienor seizes an opportunity: She will remain and nurse Lavinia; Goffredo will take her place with Alexandre.

The relationship between the two males shifts from none to a father-son-like intimacy. We observe the process taking place while Raphael O’Byrne’s camera skillfully surveys sublime domes and facades. The men speak of convex and concave in the same monotone they use to discuss love, and, in the case of Alexandre, confess past indiscretions and confide extremely private matters.

The strategy is pure Green. He transposes baroque theatrical devices to film. This calls for stilted speech and direct address to the camera. Artifice is the base. The usual distractions for understanding a character are lacking. We are left with dialogue itself. It may sound boring, but it is anything but. I call it fascinating.

Everyone has their demons. Proximity to the youngsters helps Alexandre and Alienor deal with ghosts from their marital past. Lavinia and Alexandre in particular benefit from the contact. It is all brilliantly circuitous.

If you must assign a genre to the film, it would have to be stylized minimalism. Whatever it is, architecture history has never been more vivid.

Two Days, One Night (Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, Belgium/France/Italy)

Even-keeled, but with an imaginative, unexpected punch as a payoff, the Dardennes’ latest foray into socially conscious cinema (Rosetta, The Kid With a Bike) is a potent isomorph of the typical management-versus-workers scenario: cynically, the bosses pit employees one against the other.

Sandra (a perfectly nuanced Marion Cotillard, the rare star to appear in their films, though looking only about as run-down as is possible for such a gorgeous woman), a decent, ordinary working-class wife and mother, returns from a leave of absence from a factory that produces solar energy parts to be treated for depression. The boss, having noticed that 16 people have achieved the same output as 17, offers the others a choice: Sandra’s job or a 1000 Euro bonus each. In a vote held on a Friday, 14 choose not so much to go against her but rather in favor of the bonus — depending on how you look at it, especially in light of today’s economy. Only two vote in her favor.

After coaxing the director to hold a second, secret ballot on Monday morning, she has the title’s two days and one night to canvass her colleagues one by one, in their homes or sites of weekend recreation, to change their vote. Not a simple task, given that she still suffers symptoms of depression — she gets by at the mercy of Xanax — and the foreman is counter-campaigning, pressuring each of them with lies and threats to maintain their earlier stance.

Her weekend hustle through the downmarket nabes of this drab Belgian town — it feels gray even during the hot summer — adds a level of suspense to this unembellished film, the variety of fellow workers and the differing explanations for their choices sustaining our engagement. For Sandra, every visit is another stop along an emotional Via Dolorosa. She is fighting for her economic survival and by extension her marriage and the welfare of her children.

Yet she is not aggressive, and the French and francophone Belgians do engage in fake pleasantries upon greeting and departing. Just by her presence and honesty, she pushes buttons. Several are conflicted, their sense of loyalty to her personally and feeling of camaraderie up against the negative force of spouses, superiors, and bill collectors. The schism can be extreme: we see marital breakup, violence, emotional breakdown. Whatever the response, there is always a double kiss and an a bientot to top it off. Until the coup de grace…

Sandra’s plight is a microcosm of the world’s management-friendly economy. As small as it may seem, her struggle is Sisyphean, the odds so stacked against her. The only support comes from her patient husband, Manu (Fabrizio Rongione), and a single high-energy co-worker, both of whom have to pick her up off the floor more than once over the weekend. Those most responsive to her plight turn out to be immigrant males of color; the least, white males and spouses of either sex. Female colleagues fit right in the middle; feminism is hardly a factor. But then, even after May ’68 and the Polish Solidarnos, among other movements, solidarity among workers appears to be — well, almost — a thing of the past.

The Blue Room (Mathieu Amalric, France)

Amalric (On Tour) himself portrays the married Julien, the classic part of a man convicted of a crime he only wished to commit. Adapted from a book by the great Belgian detective novelist Georges Simenon by himself and Stephanie Cleau (who plays his married pharmacist lover, Esther), Amalric creates an appropriatlye rich atmosphere in a provincial town for a femme fatale to engage in an affair with a bourgeois man, and for sex to play a major role in creating suspense. To his credit, Amalric keeps his cards close to his vest. We don’t know what the crime is until two-thirds of the way through the film.

Julien is a successful salesman of farm machinery, his wife Delphine (Lea Drucker) a dutiful housewife who has lost her sexual allure. The only joy he gets from his marriage is their young daughter. Several times he involuntarily commits small, nasty physical acts toward Delphine, like holding her head a bit too long under the sea and nearly knocking down a tall ladder she is standing on. He acts as if he is joking, but she doesn’t miss a thing.

Amalric plays the man as a nervous wreck. For her part, Cleau is calm and controlled. Her husband is ill; some in town say she is only interested in his family’s money. When Julien tries to pull away, he is like the fly caught in the spider’s web. Eventually he is accused of murder. We are not sure of Esther’s part in all this, but the magistrate, Diem (a marvelously creepy Lauent Poitrenaux), becomes unhinged by all the talk of an illicit liaison.

The theme of investigation, not just of the judicial variety, keeps popping up. The camera dissects the remnants of a lovemaking session, like blood on the sheets and a pubic hair. In fact, the sex scenes look like murder scenes.

We see elements of Chabrol, Hitchcock, Lang, Preminger, and Resnais, but Amalric owns the final product. During a trial, a face-on montage of successive witnesses stresses their subjectivity. An exit from a courtroom is filmed like a final curtain. A sense of claustrophobia pervades the film, as does the nostalgia of a conventional thriller, with academy ratio and classic studio music put to powerful effect.

SPOTLIGHT ON DOCUMENTARY

Stray Dog (Debra Granik, US)

The choreography of heavy-duty bikers appears more and more similar to military formations once you’ve entered the world depicted in this doc by Granik (Winter’s Bone). Most of the men who ride with Ron “Stray Dog” Hall are, like him, Vietnam vets, scarred by the past (Hall is just one with PTSD) but stuck in it as well, reenacting the tight male bonding of that peculiar war and the rituals that keep the memories sanctified. These men are deeply patriotic.

Anyone who thinks bikes or bikers are scary will have their delusion dispelled after watching the film: the men are softies, mostly troubled but gentle. The bikes are just the means to hold on to a group identity when rank and serial number are meaningless, and instead of Viet Cong, poverty and unemployment are the shared enemies.

Granik centers the film on Hall and his family, including his second wife, Mexican immigrant Alicia, and later on her twin teen-aged sons, who join them in the RV park he runs in Branston, Missouri. The filmmaker also branches out into the larger community and its social and economic concerns.

Hall is complex, and, like the film itself, occasionally reveals a humorous side. He is an open book, recalling his anger after returning from the war — he had a string of assault charges — and his first marriage to a Korean woman. We meet his daughter, granddaughter, and great-granddaughter, and see that same large well of emotion and warmth that emerges whenever he speaks of friends who died during the war. He is, above all, human, just like us.

Although he admits to having made many mistakes in his life, he takes on a firm but loving parental role with his granddaughter and Alicia’s sons, offering them guidance and pushing the importance of goals and responsibility. He may wear a bandana over his skull, a leather jacket and boots, but underneath he is a fairly conventional man.

Granik and Hall do not shy away from such private topics as geriatric issues. He and his pals talk about the best places to buy Viagra. With another buddy he discusses inexpensive dentures, and he watches the fellow pull his own tooth to save $300. Hall embraces his senior status without denying it.

The Look of Silence (Joshua Oppenheimer, Denmark/Indonesia/Norway/Finland/UK)

The “look” here has a couple of referents. One is the cumbersome device that rests on your nose when being measured for eyeglasses. You’ve surely seen in posters and stills for the film this contraption that is a tool of optometrists, such as the soft-spoken, 44-year-old Adi Rukun. Putting his professional device to good effect, this rural practitioner offers his services to aged former mass murderers of anyone thought to be Communist during the 1965 Indonesian bloodshed who still reside in his home district.

After he’s gained entry, Rukun tells them the real reason he wants to meet them: he wants to confront those responsible for the gruesome death of his brother, Ramli, who would be two years his elder. It was truly horrible: men took the injured youth from his parents’ home, ripped out his intestines, cut off his penis, then drowned him. Such images linger heavily in the mind of his old mother, understandably obsessed with revenge and with this younger son who was meant to replace him. She channels the rest of what remains of her will to live into caring for her nearly vegetative husband. Catharsis is nearly impossible in villages where perps and survivors still live side by side.

The other significance of the “look” is the nearly blank expression on Rukun’s face while he watches specific clips from Oppenheimer’s prequel, The Act of Killing, before venturing out to meet the unrepentant, often gleeful, self-proclaimed torturer and murderer he has just observed. The viewer has to project interpretation onto that expressionless human canvass, with only sound from the first film as a guide. His silence and our own merge. What we see becomes an unconscious fusion of that empty face and our own interior psychological constructs. Few filmmakers reach their viewers at this psychological and emotional level.

Rukun keeps his cool even in the most trying of circumstances. One man brags about maiming his brother, another threatens him; yet a third, an uncle, cops an I-was-only-following-orders plea. Most, of course, prefer not to bring up the past. Unfortunately, attitudes have changed little in the nation. Rukun’s children’s textbooks recount that chapter in the country’s history with colorful negative stereotypes of Communists deserving of their fate. Thankfully, he has a positive outlet: he corrects his kids and by extension, future generations of Indonesians, telling them the truth behind the horrors of ‘65.

The 50-Year Argument (Martin Scorsese, David Tedeschi, US)

Many Scorsese films are marked by his unique elaboration of form. And increasingly, docs show that attention is being paid at least as much to structure and style as content.

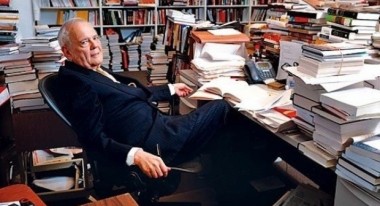

This film falls into neither category. It is a sober, highly subjective, unashamedly hagiographic history of a very special publication that is held dear not only by New Yorkers but to those tuned in to the great ideological debates and culture and political wars of our and prior times, a bastion of independent opinion segregated from boards and large advertisers: The New York Review of Books. Invited to make a film by its top man on the occasion of its 50th anniversary, Scorsese and co-director Tedeschi celebrate the NYRB as only its admirers can. I must say, I cannot pretend to be objective about the film: this is the only publication I consistently subscribe to, for one. That said, this is the type of doc in which the content alone makes it well worth watching and reviewing.

The film centers on co-founder and editor Robert Silvers, who at the age of 84 seems to live in some ways in another era, one pre-electronic, more writerly, and text-friendly. Yes, books are reviewed, but that is not the primary concern. Heavyweights argued (Mailer, Sontag, Vidal) and still do. Alternatives and unpopular points-of-view are explored (Tahrir Square, Iraq). Silvers can sniff out the zeitgeist (Michael Greenberg on Occupy Wall Street). Philip Roth writes and is reviewed; same goes for Joyce Carol Oates and Colm Tobin, ad infinitum. Art exhibitions from all over the world and the occasional film are reviewed. This is an intellectual mélange with a progressive, questioning agenda. Like Woody Allen with top actors, Silvers gets the very best writers because he can.

In the film, living authors discuss some of their exemplary pieces, preceded by a beautiful photograph taken by Brigitte Lacombe. Archival footage does the talking for those no longer around. These give a visual structure to the doc in between worshipful scenes of Silvers, surrounded by books, working in his office and mingling with the faces behind the bylines and a few bold names over cocktails.

Not everyone knows that had the New York Times been available during the 1963 newspaper strike, the idea of the NYRB might never have come into fruition. Nor that the jumping-off point was a biting piece that appeared in Harper’s in 1959 by writer Elizabeth Hardwick, a co-founder (with Silvers, co-editor Barbara Epstein, and publisher A. Whitney Ellsworth), called “The Decline of Book Reviewing.” The article set the tone for the NYRB’s style, argumentative and provocative, to put it mildly. And not everyone remembers that this was the lone publication on the record against going into Iraq from the very beginning. The 50-Year Argument reminds those who do know, and educates those who do not.