Back to selection

Back to selection

Transmedia is Still So Young: Femke Wolting and Tommy Pallotta on Last Hijack Interactive

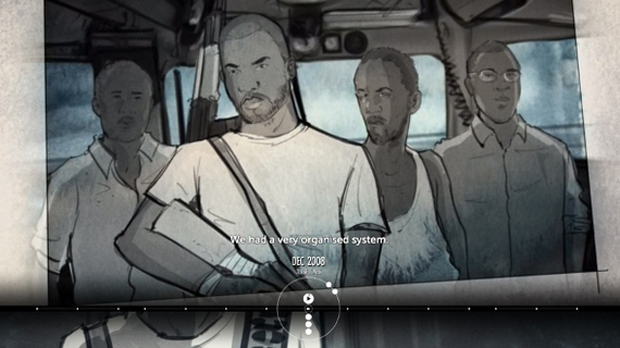

Access is always an issue with documentary, creating unique challenges in war zones or similar areas where filmmakers would be in physical danger or simply cannot go. The documentary Last Hijack, produced by Submarine Channel and directed by Femke Wolting and Tommy Pallotta, doesn’t just deal with these issues but makes them one of the film’s greatest strengths. In documenting piracy in Somalia, the filmmakers turned to techniques like animation — Pallotta produced both Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly — to show what could not be filmed, and then went one step further by creating an interactive documentary to accompany the traditional linear film. This version allows viewers/users to control the narrative flow and delve more deeply into certain aspects of its characters’ lives, including both Somali pirates and European hostages. The project had its premiere earlier this week at the New York Film Festival, where Wolting and Pallotta spoke about the creative process of producing an interactive doc. A trailer for the linear film and the complete interactive film are currently available at lasthijack.com.

I spoke with the directors about filming such a volatile subject and the process of creating two projects — one traditional, one new media — from the same raw material.

Filmmaker: Let’s start with the original (linear) documentary. What got you interested in this subject and how did you get access to the Somalis featured in the film?

Wolting and Pallotta: We got interested in the subject when we saw news footage of pirates in tiny boats trying to climb on huge oil tankers. It was such a strong image, and pirates seemed like something from another era. We started reading about piracy and found out there is a whole world around it, issues of globalization such as illegal fishing and waste dumping. The media reported only about the western perspective, and we became fascinated to know who these pirates were and what drove them to risk their lives and go out on the ocean.

We researched for about 18 months before we found Mohamed. Many of the pirates were not willing to speak about their activities because they hope to move to Kenya and the west, so they can’t say too much in fear of being arrested later. Many of the pirates were just young kids sent out on the little boats without knowing much about what was going on. We worked with a Somali journalist, Jamal Osman, who was incredible, and he found Mohamed. He is a very experienced pirate and had no intention to leave the country and was therefore willing to share his life with us. The parents were trying to convince their son to give up piracy, and they thought that the fact that Mohamed took part in the film was a positive thing, so they supported that and also were willing to share their lives.

Filmmaker: Do you consider the interactive documentary an adaptation of the film, an augmentation, a companion piece, or something else? At what point did you decide to create an interactive doc and what did you hope it would convey that a traditional film couldn’t?

Wolting and Pallotta: We see it as a companion piece; you can enjoy the film by itself, and the same with the interactive doc. But if you have seen both, they get the different perspectives of piracy.

The film is made from the Somali perspective, and we thought that an interactive doc would give us the opportunity to juxtapose the Western and the Somali perspectives. In the interactive doc, you can navigate between the story of an English captain, who was hijacked by pirates, and the pirate Mohamed. The interesting thing is that they have dealt with the same issues, like the effect of over-fishing. Also the period that they were both on the ship, one as kidnapper and the other as hostage, there are interesting similarities. Then you can branch out and explore the causes and consequences of piracy. We interviewed a mix of people from both sides: on the Western side the negotiator who makes deals between the shipping companies and the pirates, and on the Somali side human rights lawyers, and a father who lost his son who was a pirate.

Filmmaker: Submarine has a long history of new media production, and each of you individually has experience working with interactive material before. What’s the collaborative process like working with coders to create something cinematic? In this piece you brought in animators as well to illustrate material, such as hijackings, that couldn’t be filmed.

Wolting and Pallotta: Transmedia production is a collaborative process, just like film. In film all the roles are clearly defined, because film has been around for more then a century, so everybody knows exactly what to do. In transmedia, directors, animators, coders, designers work together as a team. Everybody needs to work closely together and experiment, because the medium is still so young. A director needs to work closely with coders to come up with innovative interfaces to create an interesting and accessible experience. They are as much part of the artistic process as a d.p. in film.

Filmmaker: User navigation doesn’t exist in traditional films, but it’s fundamental to the experience with interactive pieces. Here the main navigation tool when the film starts playing is a timeline. Can you describe how it works, both horizontally and vertically, and how it affects the experience individual viewers can create?

Wolting and Pallotta: The user interface is a timeline, in combination with two perspectives. The timeline starts in the ’90s and runs until the present day. The timeline gives the opportunity to explore piracy from its origins to the consequences of piracy today and the near future. Then you can navigate horizontally and vertically between the perspective of the UK captain and Mohamed the pirate. There are different themes, such as the negotiations that they both reflect on through their personal experiences. The user interface is set up in a way that the experience is continuous, so the user can interact and navigate the story in a participatory manner, but if you choose not to, the experience continues, and you can enjoy it in a more passive way.

Filmmaker: What other features, such as text, did you use to augment the traditional video material?

Wolting and Pallotta: We created a number of data visualizations that show information in a cinematic way. For example you can explore where the money that’s made by the pirates goes, so you see that most of it ends it the west, through the negotiators, insurance companies etc. In the Netherlands we made a special version of the documentary with the newspaper NRC, where the newspaper added articles from the last decade within the framework of the doc, so that people can explore the context of piracy further.

Filmmaker: Given that autonomy on the viewers’ part, how did you maintain a narrative flow over the material? It still remains easy, for instance, to follow the timeline from beginning to end, or even watch every single scene.

Wolting and Pallotta: We believe strongly that a transmedia experience needs a dramatic arc, in the same way that a film has that. So we try to design the experience in a way that the user can navigate the doc, and experience a beginning, middle and end of a story, even when his experience will be different from the next person who watches the interactive doc.

Filmmaker: With the NYFF premiere and online launch, what’s the next step for promoting the two films? What do you hope to accomplish with the release?

Wolting and Pallotta: We hope that people will watch the online documentary on submarinechannel.com. Also we are exploring licensing the doc to other networks. In Europe we have sold the interactive doc to a number of broadcasters and publishers, who then publish the doc within their channel, and we are interested in exploring these options in the US as well.