Back to selection

Back to selection

Living With Lincoln: An Interview with the Filmmakers

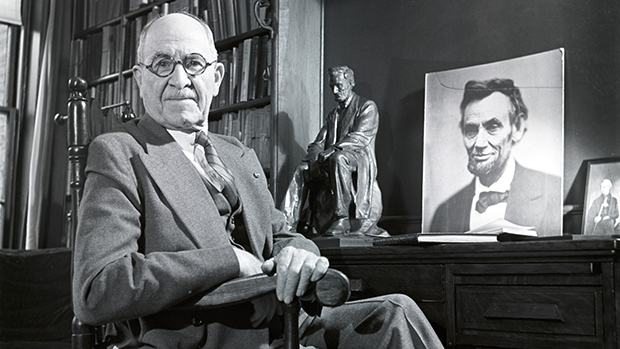

Frederick Hill Meserve | Kunhardt Family/Courtesy of HBO

Frederick Hill Meserve | Kunhardt Family/Courtesy of HBO In the late 1890s, Frederick Hill Meserve, the son of a Union solider, started collecting photographs from the Civil War. Collecting images — particularly those of President Lincoln — became something of an obsession, and he eventually acquired the largest single collection of Lincoln images. Meserve’s collection was used as the basis for the penny, the portrait on the $5 bill, the Lincoln Memorial and Mount Rushmore. The collection is vast — over 70,000 items — and became a family project for five generations. As if this didn’t sound more amazing than the plot of National Treasure, it gets better: Dorothy Meserve Kunhardt, Frederick’s daughter, who assisted him in much of his research, authored the iconic children’s book Pat the Bunny.

This month, HBO is airing the documentary Living With Lincoln, which tells the family story of the Meserve-Kunhardt Collection. We spoke to producers Teddy and George Kunhardt, co-director Brian Oakes, and co-producer and co-editor Chris Chuang about the making of the film. The program premieres tonight.

Filmmaker: How did the project come about?

Teddy Kunhardt: Two and a half years ago, we approached HBO with an idea to do a film on Lincoln, which was pegged for the 150th anniversary of the assassination. They loved the idea but wanted us to tell it in a way that was uniquely our own. We have this large collection of photographs and memorabilia started by my great-great-grandfather, Frederick Meserve, and nobody has really told the story of how the collection came about, so we re-pitched the idea of telling the conception of it.

Filmmaker: What was the process of making the movie?

Oakes: Teddy, George and Peter [their father] were working on the film for a good year before Chris and I joined. Chris and I come from a graphic design/animation/art direction background. There were a lot of ideas of how we were going to present this. We didn’t want to do the traditional approach of scanning the photographs and presenting them on the screen. We wanted to film the archival imagery in an environment that made sense to the story. We suggested a film shoot where we would set up these scenes with the actual objects and shoot them there. This allowed us to get away from talking heads. There are no talking heads in this documentary, it’s all voice over and scripted. That process was the first step in creating the solution for the story. The idea escalated, and we ended up shooting about eight days in upstate New York. We created an attic space where the collection was held. We recreated bedrooms and rooms of the Meserve office, all art directed with the collection.

Teddy Kunhardt: We brought on Brian and Chris because what we had originally started was a very flat traditional style documentary of pans and zooms. Brian and Chris re-imagined different ways to look at these objects and everything you see on screen is their imagination.

Filmmaker: How did you plan the production? Did you write a script first?

George Kunhardt: We spent a good year writing it. We were tweaking the script until the final days of narration with the guidance of Chris and Brian. In our attic are letters and diary entries from our great-grandmother, Dorothy Meserve Kunhardt, detailing all of her research and her findings. We pieced it together like a puzzle into the narration: it’s all told in her words, and our grandfather’s words, and our father’s words, and Carl Sandburg’s words. There’s some things we included that were not original writings, but our theme has always been “in their own words,” which is also a series that we produced for HBO. We tried to continue that by doing a Lincoln In His Own words, but told through our family members.

Filmmaker: What was the time span for the production?

George Kunhardt: Two and half years. The first year was research and digitizing materials, and then a year and a half with Brian and Chris and their team. There are two other people I want to make sure we mention, and one is our extremely talented director of photography, Clair Popkin. The second person is Alan Menken. He created the themes for the film. He’s best known for composing the music for the Little Mermaid and a lot of very well known Disney films, and he helped bring it to life.

Filmmaker: What was it shot with?

Chuang: Clair wanted to use Cooke lenses to get what’s known in the industry as the “Cooke look,” to give the collection a vintage feel, and get some really nice depth of field and bokeh. We used the ARRI ALEXA to do much of our shooting, and then we combined it with footage shot on the Sony F55 as well as a Super 8 camera that the Kunhardts got.

Filmmaker: Why was the Sony F55 used?

Chuang: The ALEXA was shooting heavily production-designed sequences, but we also had sequences of the Kunhardts going through their archive that we wanted to capture spontaneously and we chose more of a documentary camera for that.

Filmmaker: And the Super 8 camera?

Chuang: There was a lot of Super 8 archival material and we supplemented it by shooting some of the scenes in Super 8.

Teddy Kunhardt: Very little of the Super 8 footage was reshot. It was all my great-grandmother’s footage.

Filmmaker: Was there any material from other sources?

Teddy Kunhardt: 99% came from the Meserve-Kunhardt Foundation, then Brian and Chris and their graphics team created grids and the dissolves and all the transitions.

Filmmaker: What was the post-production done in?

Oakes: We finished in Final Cut 7, and it was probably our last Final Cut production. We do all of our graphics in After Effects. We had a pipeline in the studio that would go back and forth between After Effects and Final Cut. There was a point in the process where we migrated an early version of the project that was cut on Avid to Final Cut. That was done in order to fit the pipeline when the project became more graphics and effects heavy.

Filmmaker: Did you encounter any issues shooting or scanning these archival materials?

Teddy Kunhardt: The beauty of owning all this material is that we could handle it in a way that most people traditionally don’t handle it. We were able to shoot it however Brian, Chris and Clair wanted it done.

Oakes: One of the pieces of the story is that Peter’s grandmother, Dorothy Kunhardt, was the author of Pat The Bunny, which is probably the most well-known children’s book in existence. They have her prototype book of Pat the Bunny, which she handmade back in 1940. So along with all this Lincoln and Civil War photography, you also had this other American cultural object, and having that was quite amazing as well. As far as handling things, we did as much with white gloves as possible, but we kind of went by what Peter, Teddy and George would tell us to do.

Filmmaker: Any advice you would give to someone undertaking a project like this?

George Kunhardt: The best piece of advice we got was to work with a design team to shape it before going too far into the project. Had we not gone this route, the film would not have been nearly as important and well-done as it is. A lot of people think of a design team as a secondary thought; my advice is to go to them first, because it makes or breaks a film.

Teddy Kunhardt: The most important piece of advice that I could give is to find a group of talented people who are amazing at their job and that you like to work with. We got very lucky, we all like each other and respect each other, and it made working on this film a pleasure. These guys are the best at what they do and you can see it in the product.

Chuang: So much of the film is about Dorothy’s creative struggle and I think a lot of people who create things will be able to relate to her character, who is basically stuck, not being able to write anything for years. She was given the advice to “just do it,” and that helped us along this process too. Being able to maintain open channels of communication with the people you are making a film with is so important. Being able to see something that the film needs, and to say it openly and to do everything you can to make something that you are proud of, I think that’s something I learned during this whole process.

Filmmaker: The release of the film coincides with the collection leaving the family. Did that impact the film in any way?

George Kunhardt: The ending of the film is about letting go. The collection has just been acquired by the Beinecke Library at Yale University. We started the film before that even came into play, it just worked out well, and we’re very excited by it, but it did not have anything to do with the film itself. It’s very emotional for our family. Teddy and I have worked with the collection since we were in our early teens. Our father helped his father move it to four different locations. It’s been in our blood.

Filmmaker: Does the film represent an ending point?

Teddy Kunhardt: Absolutely. It’s equivalent to my dad writing a memoir. This is the final chapter in his book about this collection that’s consumed his life, and our lives, and our grandfather’s life, and our great grandmother’s life. It’s a very poignant moment that not only is this film airing, but the collection is going and we’ll no longer have that identity with us.

See also:

The New York Times: Yale’s Beinecke Library Buys Vast Collection of Lincoln Photos

Kunhardt Films: Living With Lincoln