Back to selection

Back to selection

Locking Gaze: Kirsten Johnson on the Images of Her Thrilling Documentary, Cameraperson

Both memoir and essay film, Kirsten Johnson’s Cameraperson is an astonishing work of cinematic analysis and alchemy. Comprised of material shot by Johnson for 24 different documentaries over a span of 25 years, it’s a movie made up of fragments, globetrotting scenes that tumble one after the other, announced by title cards listing the location and year of the footage but not the director. Included, too, in the footage is personal material, some for film projects of Johnson’s that have yet to be realized and some home movies shot of her mother in the months before she died of Alzheimer’s. Abstracting this footage, much of it outtakes, from the projects it was originally created for, Johnson — long one of our keenest documentary DPs, whose credits include Citizenfour, The Invisible War and Fahrenheit 9/11 — captures all the heartstopping, anxious, and surprising experiences of verite image-making. Along the way, her film deepens into a complicated analysis of the power structures inherent within the documentary form, revealing to us the implicit contracts between director, subject, viewer and, yes, cinematographer created every time a camera is switched on.

Cameraperson premiered this year at the Sundance Film Festival and recently won the Grand Jury Award at Sheffield Doc Fest. For Filmmaker, Vadim Rizov did an excellent interview with Johnson online out of Park City, so to cover the film for this print edition, I decided to take a different approach. I picked 11 still frames from the movie, from scenes that made a particular impact on me, and sat with Johnson as she pondered the meanings, associations and emotions they provoked. While the intent was to transport her back to the circumstances of shooting those scenes, something different resulted, as she notes in these final comments, which she asked me to restart my recorder to capture:

“Of course, I’ve seen Cameraperson, the film, many times, so I am rather surprised to experience how completely and distinctly different it is for me to look at shots from the film as still images. In each of these frames, I am seeing something different than I have ever seen while watching the film. The fact of stopping the moving image and freezing the frame allows distinct details to reveal themselves. It gives me new insight into how much more is still hidden to me in Cameraperson.”

Cameraperson is in theaters Sept. 9 from Janus Films. The following text is all from Johnson.

A teenager discusses her abortion in Trapped, directed by Dawn Porter.

Over years of filming, I return again and again to certain frames, like this one of hands in a lap. When I first started shooting, I’d shoot cutaways of hands while people were doing interviews in an almost perfunctory way, like one is taught to do, and then, I started actually seeing how much was coming through in the hands. Once I really started paying attention, I realized that I was learning completely different things from watching a person’s hands as they were speaking than I’ve learned from their words. The other thing going on here is the nice tension between those fashion-forward, ripped jeans that are her choice, and the way they reveal her body in the same moment that she can’t reveal her body in the larger sense. All of the struggle and love of this moment, she’s expressing in her hands. There’s despair and tenderness in the physical way that she holds onto herself.

I’ve always resisted the idea of B-roll. I’ve sought different language to describe it, because I think when a director tells you that you’re going to be shooting B-roll, it’s almost like this idea of being told you will be shooting B-camera — there’s this idea that it’s a secondary thing, that it’s not as important. My feeling about B-roll is that it’s a term that encourages a lack of investment in the action. Every shot is a search for A-roll.

A newborn baby fighting for life in a Nigerian maternity ward in The Edge of Joy, directed by Dawn Shapiro.

I was trying to get pregnant when I was filming these scenes in this maternity ward in Nigeria, but I hadn’t had children yet. I knew so little about babies and medicine, so, of course, I didn’t know that it was impossible for the baby to actually see me in that moment. I totally believed that the baby could, and the woman who is saying, “Look, the baby’s looking at you,” she’s a specialist in maternal health, so she must know it’s impossible. But I love the magical thinking that we are all sharing in this moment. It really does feel like this child has entered the world eyes wide open and is connecting and seeing.

One of the things that has floored me in going back through so much footage in order to make Cameraperson is that I found myself recognizing everybody. I’ve realized through watching all of this footage again that every time I have really looked into the eyes of a person, that it is stored somewhere inside of me. I have actually never forgotten them. As soon as I look back at the footage, I recognize that person. And so, I look at this baby, and the other baby seen later in the film, and their eyes are imprinted in me. This was something I didn’t understand or believe to be true before I went through this process.

I have no idea why that is, or where it’s stored in the brain, but there is recent thinking about how Alzheimer’s functions that suggests that it’s the retrieval mechanism that’s failing, not that the memories aren’t in us. The idea is that the memories are inside us, but we just can’t get to them. Realizing that I can see footage again, five, 10, 15 years after shooting it, and I can see a person’s eyes and say, “I know you” — that has raised the hair on my arms. And that’s part of the love and loss of this process, right?

The boxer James Wilkins just after losing a match in Bartle Bull’s Cradle of Champions.

What I love about this particular image is that it is him in bewilderment, this hands down moment, when all of the violence and rage is still in him but he doesn’t know where to go with it. And I think that is how violence functions: it overpowers a person and then it can go anywhere. Any of the violence I have experienced in my life, I have always been blindsided by it. You can never see it coming.

I was invested in him from the time I spent shooting him before the fight, just because he was letting me be there, right? It was the finals, so it meant a lot for him to let me in while he was warming up. I had filmed with him very little over the course of the run up to the finals, and we didn’t know each other, but I really wanted him to win, because I could see how much he wanted to win. And when I saw his defeat, I knew his anger was coming, and so I prepared myself to be ready to be with it. But then it went beyond what I expected. I love how there is the moment that makes us wonder if maybe he is coming at me and could hit me or the camera, but then later in the hall, he turns around and looks for me as if he needs me to be with him. Being with a person and filming that person — I love the mystery of that.

It’s clear that he is humiliated by his defeat, and when I was shooting I knew I was creating an indelible image of that defeat. So, inadvertently, I am engaged in contributing to someone’s humiliation. I think that’s part of the tension that I feel — do you continue, or not continue, shooting?

Darfurian women chopping a tree in Ted Braun’s Darfur Now.

There can be such a sort of high-minded earnestness around how to present people whose lives are in the middle of full-blown conflict and great suffering. But these women were hilarious, completely capable of laughing at the absurdity of the horrible situation that they were in. They were defiantly saying, “Yes, we chop down live trees. We really don’t want to, but these bastards are not letting us do anything else!” They also could have been laughing at the absurdity of me being there with my giant camera in the middle of that desert refugee camp, where there was so little of everything they really needed.

The director had asked me to include them chopping down the tree in the distant background of another shot. That happens a lot in filming; we see something and think, “Oh, that’s a powerful image.” I’m always struggling to not see people as “powerful images” but to look at what’s really going on with them. I wanted to talk to these women who were so far away in my first shot of them. And then to find them able to laugh and see the absurdity of their situation was a marvel to me. That’s the kind of surprise I’m always searching for in these relationships. So much of the time we are foregrounding people’s victimhood. I know much of that is a necessary responsibility and obligation, but such scenes often don’t capture the rest of their humanity. So I love it when the singularity of people shines through.

A Bosnian teenage girl in Pamela Hogan’s I Came to Testify.

This one really stops me cold just because she’s so on the cusp. You know, she was embarrassed the first time I filmed her, and I think she was embarrassed here, too, in a certain way, but utterly thrilled to see herself changed from my earlier footage of her. We ended up having this remarkable conversation with all of the women in the family about her. She had been in a UN-sponsored school that was actually talking about the Bosnian conflict, whereas all of the other schools in the area were not speaking of it. She had gotten in some fights, and they weren’t sure if she was going to be able to go back to the school, and her mother and the aunt and the grandmother were all worried about her future. Everyone was talking about how soon she was going to get married, and whether she could make it in the city or needed to stay in the country.

It felt like she was in this moment of turmoil in her life, and me showing up with this footage and reminding her of her childhood, and sharing a reason to imagine another world — it just felt like something might come of it. I think I connect to it because I feel like I was raised within this hermetic worldview of Seventh-day Adventism, where I didn’t quite imagine that other worlds were possible. And so, as much as I often critique the status of an outsider who comes in and disrupts, misunderstands or misrepresents things, I also often realize that an outsider brings some glimmer of a different possibility. I felt that happening between her and me, that somehow seeing me and all the ways that I made no sense to her opened up some strange sense of possibility in her. I’m very excited to go back and have her see Cameraperson and see where she’s at in her life.

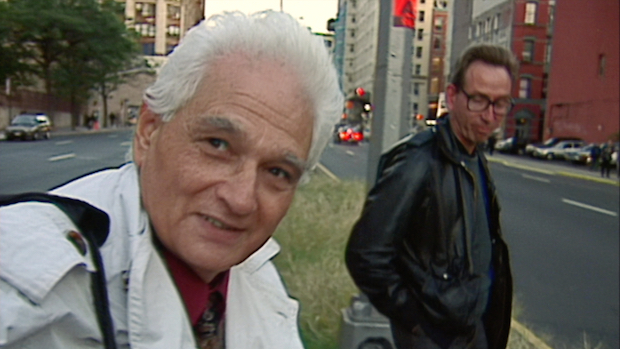

Philosopher Jacques Derrida in Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering’s Derrida.

There’s no question that Derrida didn’t just keep me from getting hit by a car, but saved me in many ways. What’s fun about this particular image is that it’s just like what he says, he is the philosopher who stares into the well — he really is falling into the lens in this moment. Filming Derrida was intimidating. He spoke with as much rigor as he wrote. His intellectual prowess was formidable. And I also think he was interested in being a provocateur — challenging people, getting them off balance. To this day, I somehow believe that he was interested in pushing me away from words and toward images. I was very chatty, doing these “witty asides,” trying to prove to him that I was clever. I wanted to have a connection to him. I didn’t want him to not see me. At a certain moment, when the team was filming in his house, he said, “I want you all out of here. I can’t concentrate; I need to be by myself.” Amy begged him, so he gave in and said, “Kirsten can stay with the camera if she doesn’t say a word.” I think of that now as this incredible gift. I stayed for eight hours in his house just filming him, not saying a word. He gave me the space that I couldn’t yet give myself to understand that my thinking could be displayed in the images that I created.

A man filmed while praying in a mosque in Kirsten Johnson’s unfinished A Blind Eye.

What’s so great about this entire set of images is how much it is about the connection of eyes. I did have permission to film in this mosque. But it was one person’s permission — the man who is singing had given his permission. And then, this other man walked in. We had seen him earlier, when we were filming outside, and he had yelled something at me — clearly he didn’t want me to be filming. When he came in, he didn’t see us initially, and he was praying. And then, he turned, and I just think it was so outside his realm of possibility and imagination that he was just kind of stunned at the impossibility of seeing me in that space. The totality of his shock was so interesting to me that I held the shot for as long as I could hold it.

At different moments in my life I would not have been able to hold that shot. But, I will say, I took some real pleasure in being able to be in that mosque. I think that’s part of my own relationship to the impossibility of transgression within my religious childhood and some fantasy I had that something or someone would transgress the religious space. And so, often I act that out. I am drawn to film in people’s religious spaces, and I have many feelings about it. I can feel very reverential and also like I am being deeply disrespectful, and I worry about it, and try to check myself, but I bring to it the fact that at one time in my life I was a religious believer. Leaving this man’s staring shock in the scene reveals the deep quandary of filming a person’s religious privacy.

Johnson’s mother from personal home footage.

If it was my choice I might want to pick a different frame of this, just because there’s something dull in her eyes — an absence of the gaze. I don’t see my mother here because her eyes are so flat. That’s what happens with Alzheimer’s — the person goes into this blank zone. So many people who have seen Cameraperson say, “Your mother looks exactly like my mother, my grandmother, did when she had Alzheimer’s.” So maybe this is the still image to look at because it’s the loss of the gaze that is such a part of the loss when a person has Alzheimer’s. In some ways, doesn’t it look like she’s looking back into her own mind? But that’s the search, right, the search we do as humans with each other — “What’s going on inside you?” And certainly with Alzheimer’s, you’re constantly searching — is the person you love there, are they not there? Is this real, is this not real?

My mom, I remember we were watching TV, and she had gotten really confused looking. And she said, “So where does the edge of them end and the edge of us begin?” And all I could think of was, “Excellent question. That’s what we’re all trying to figure out.” Despite the flatness in her eyes, she knows something about what’s going on inside of her that I can’t know, and you can see that in this shot.

My mother never wanted to be filmed. In the first scene of her in the film at Headquarters Ranch in Wyoming, I was sort of pretending that I wasn’t filming her. I was pretending to be filming a vacation home movie, but I really wanted to film her and was afraid to, and then she was the one who said, “You caught me.” She wasn’t happy, and I didn’t film her again because it felt like a betrayal that a daughter shouldn’t do to a mother. And then, this second time, I just had to do it. I just happened to have a camera with me when I visited her, and it was clear that she was going soon and this footage would just be for me. That’s what I thought at the time. I desperately wanted to film her, just for myself. All I have filmed of my mother is maybe six minutes of footage, and I hadn’t looked at any of it since she died until I started making Cameraperson. For me, it was all about permission: how can you really have people’s permission to use their image? My mother in her lucid state would never have accepted the betrayal of showing her this way. And so, for me to give this transgression to the world and own it feels like some kind of accountability in relation to all the rest of the people I film.

A burst of lightning captured in Audrie & Daisy, directed by Bobbi Cohen and Jon Shenk.

An image is something soundless, but seeing an image of lightning can bring the sound of thunder to our minds. We believe they’re happening together, but what’s actually happening is that lightning is this disconnected thing that thunder enhances and amplifies. And, for me, that says so many things about how sound and image relate to each other in cinema. For example, when we watch the baby’s struggle for life in the maternity ward, it is the absence of sound that makes you sit at the edge of your seat and say, “Will this baby live or die?” Pete Horner at Skywalker Sound pulled the sound out of that shot to magnify the tension and to find a way to convey in minutes what I had filmed over hours. I always feel this tension when I film — trying to figure out the relationship between what I’m hearing and what I’m seeing — and I love the way that’s separated out in our experience of this shot.

A man turning his camera on Johnson in Pamela Hogan’s I Came to Testify.

This makes me confront who I may be to other people. Filming can be so aggressive, such a taking of the person. The way in which this man tries to be stealthy by turning and covering his face with the camera as quickly as possible — it’s a way, I feel, of hiding some kind of shame. It expresses this contradiction of knowing that you are “stealing an image” and trying to find a way to pretend you’re not. Right? When I’m on multi-camera shoots, or when I’m traveling and I see another person photographing and I see other people operating cameras, I’m always wondering, is that how I look to other people?

One of the things that I really loved when the advent of flip out screens happened is that it became possible for me to maintain eye contact and shoot. In terms of the human interaction, that felt so much more comfortable to me. I’m left-eyed, so when I shoot a camera that only has an eyepiece viewfinder, my right eye is against the camera and people really can’t see my eyes. I think that I experienced much more discomfort in those years of filming with those cameras, because my eyes were hidden to people. And whatever I was trying to say with eyes — “I am humbly asking this of you” — I could not do. What that man is up to by doing that camera move so fast is completely familiar to me. “You won’t call me on this. You can’t.” There’s no question that the camera is an instrument of power. How you use it, how you carry it, how you hold it, how you interact with people is loaded in all kinds of ways. But this gesture of hiding feels like an expression of the shame one often feels when filming others.

Kathy Leichter, being interviewed and just before a burst of anger, in Leichter’s Here One Day.

Kathy Leichter is just one of the most emotionally brave people I have ever met. And I feel like together, we figured out how to push the boundaries of what we could both allow emotionally while filming. I’m not very comfortable with anger, and when I get angry, I get embarrassed about it, or I really regret it. So I try to prevent it and contain it. And it’s just interesting, when I look back at this footage I see that I basically provoked her into expressing her anger. She would not have gone there if I had not kept asking whether was more to what she was feeling.

But the intent of this project was very much an exploration of emotion. In filming it, I felt like I was continually going close to an edge and trying to figure it out. Have I gone over it? Have I not? There’s an aspect of this scene that’s so performative, where she’s starting to overdo it, but then it hits some real place. I think it is just so interesting, how performance and actual emotion collide in every kind of filmmaking. I love that that is so shifting in this scene, that there are moments where the anger seems self-conscious and then other moments where the anger is clearly very deep.

Contrary to what some have imagined, Kathy was very happy to have the scene included in Cameraperson. She desperately wanted it in her film but felt it was impossible, given how performative and self-serving it felt in the context of her own film. She had long talked about her frustration in not being able to use the shot, so it was really satisfying to find a place for it! — Kirsten Johnson.