Back to selection

Back to selection

TIFF Critic’s Notebook 4: Austerlitz, Planetarium, Tramps

Austerlitz

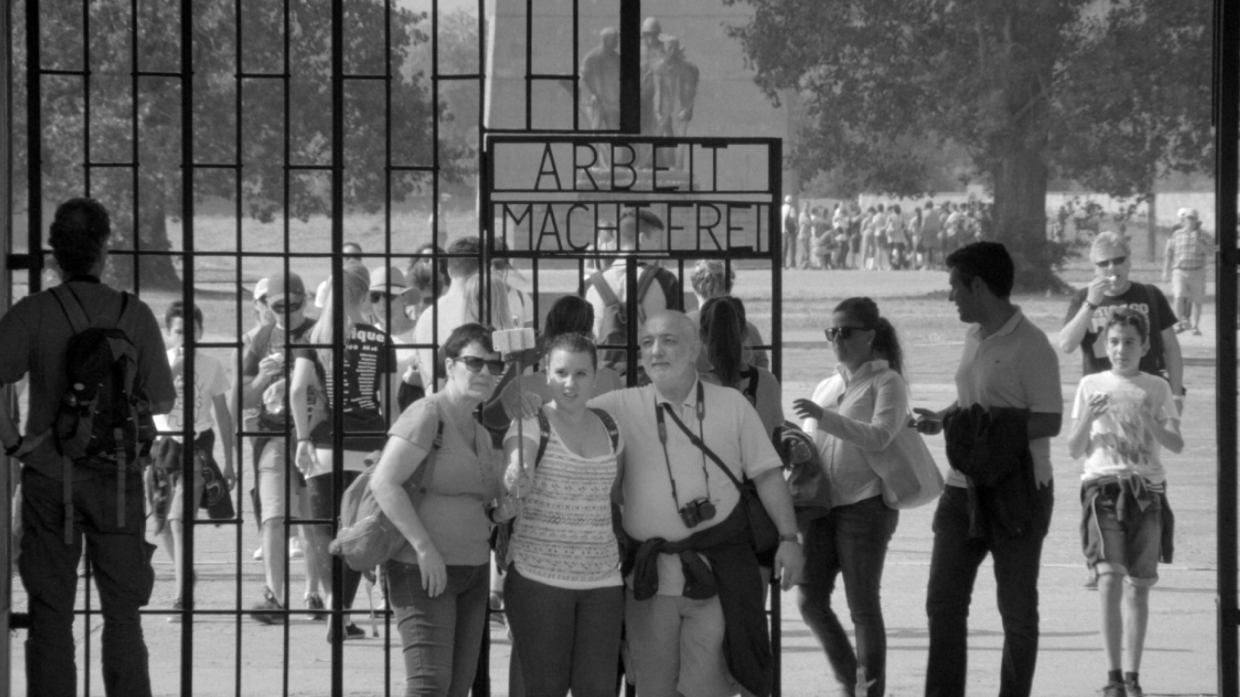

Austerlitz Sergei Loznitsa’s Austerlitz, a record of tourists visiting the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, could be loglined as a movie about why it’s a transparently bad idea to take selfies at Holocaust sites, but that would be reductive and far too banal a point to need making at feature length. The film is in low-contrast black-and-white, and how could it be in color? The visual language of extant Holocaust footage is B&W, so Loznitsa maintains visual and historical continuity. The opening movement is not that far off from, of all things, In the City of Sylvia, with long shots of tourists milling about in multiple compressed planes the audio swelling and ebbing as lone individuals, couples on dates and multi-national tour groups make their way.

People-watching is its own known pleasure, but Austerlitz is a film about the complications of performing, in public, the act of Never Forgetting. There are legible t-shirts galore: the old Batman logo, a lady on gender-norm-scrambling point wearing one of those shirts where an arrow pointing up reads “The Man” and the one pointing down reads “The Legend,” a dude sporting a Jurassic Park logo who tries to stare the camera down. Loznitsa’s gaze does not pretend to be inconspicuous, with visitors taking as many pictures of it as of the site itself; the camera is, in some sense, oppositional, the same way that any extended fixed gaze on people in public with no clear aim or intent would be.

One of the aforementioned t-shirts reads “Life was much easier when Apple and BlackBerry were just fruits,” and perhaps we could take that as a reproof of the hordes snapping crematoriums for their Facebook feeds, possibly with a sad-face emoji to accompany the pic. But I don’t think Austerlitz is a film about how smartphones have degraded our moral sensibilities: you could, presumably, have made a film 20 years ago to much the same effect, only with visitors toting larger cameras. If smartphones and Instagram culture make for easy targets, they’re just a symptom of a larger problem, not the problem itself.

Anyway, what’s the right clothing to wear on a Holocaust pilgrimage? All black? Are shorts allowed? Do people get to take a sandwich break or is that inappropriate at the site of starvation and death? To what extent does visiting such a site require appropriately mournful optics, and for whose gaze? The tourists milling about chatter, laugh, snap photos and seem to be having a good time: when they listen to their tour guides, they seem dutifully bored rather than shaken. When they take photos, to paraphrase DeLillo, they’re photographing the most photographed genocide in history, but what else are they supposed to do? What if someday they make a geofilter to make the Holocaust “come alive” on your smartphone? VR, we are hearing very often nowadays from its advocates, is conducive to generating empathy, and there’s very little of that on display, so why not? At a certain point, I started wondering if maybe taking a smiling photo in front of a crematorium was, in some warped way, a positive development — a way to stand in front of foul history and assert one’s possibly illusory freedom from it. And who has the right to tell the guy in a yarmulke he shouldn’t be posing for a photo?

Austerlitz is a film about what happens when solemnity becomes near-impossible to access, for reasons of chronological distance and the fact that any such site is visited under conditions which are the exact opposite of how it functioned — and, if that’s sad, and if it’s definitely stupid to pose smiling under a gate reading “ARBEIT MACHT FREI,” it points to a dilemma of historical imagination rather than a moral problem per se. It helps that the film is immaculate crafted and perversely non-commercial: with its long, long shots and sparse dialogue, this is a film that can’t be easily flipped and sold for a tidy profit in the vein of numerous putatively “powerful” Holocaust docs that do all the moral calculus for audiences via talking heads and archival footage. Austerlitz‘s people-watching pleasures are complicated but don’t resolve in any one direction.

All of that said, a brief note on festival etiquette: my P&I screening was, as usual for any arty film at TIFF, punctuated by a steady stream of walkouts throughout, and that’s not a huge surprise. I was, however, very impressed by the chutzpah of a guy in the third row way up front who took regular breaks to scroll through and reply to his emails and iMessages. This is terrible, terrible behavior: if you have to do that during a screening, can’t you at least sit all the way at the back? And whil I’ve just spent far too many words arguing this is not just a movie scolding people for doing the same at a concentration camp, the irony of this dude regularly checking out to mimic their behavior below is just so terribly, terribly obvious. Please please please do not be this person.

Rebecca Zlotowski’s third feature Planetarium has way too many strands. It works through elements of Esther Kahn in its depiction of a hollowed-out woman who tries to discover emotions through acting (Zlotowski cites Desplechin’s film in the press kit interview, and its influence is clear), has subplots about French institutional anti-Semitism and some early-days-of-filmmaking on-set stuff (the only fun part), digresses for a strange and stupid thread in which a teenage female medium conjures up a spirit that has ethereal mind-sex with an older man (?), etc. This isn’t the good kind of mess that’s just bursting with too many ideas to contain itself: it’s just half-assed in multiple directions.

In ’30s France, sisters Laura (Natalie Portman) and Kate Barlow (Lily-Rose Depp) tour as mediums, their nightclub act meant to drum up private seance business; Laura is the hypeman and carnival barker, Kate the sister who can actually channel spirits. Film studio head Andre Korben (Emmanuel Salinger) is blown away by their initial session at his house, whose visual language — Korben’s neck craned all the way back before his head ominously rears up again — could be that of an exorcism horror movie at the moment the demonic spirit first announces itself. But Zlotowski plays it safe and maudlin, with Anne Dudley’s insistently syrupy score backing her up. A shaken Korben decides to film the sisters and capture the experience on-screen, with the usual metaphors about movies as preservers of the ghosts of the long-departed applying.

The pioneering-days-of-film scenes feature heavily lit sets and early cameras and montages of the industry at work, and they play like a cut-rate Hugo. Korben (a character inspired by Bernard Natan, whose full story is worth a read) talks excitedly about the need to compete with American cinema, whose production values have already outstripped France’s, and extols the need to “Develop cinema again!” Clearly, some things have yet to change (despite Luc Besson’s best efforts). These scenes are also a fantastic showcase for Portman, a sometimes annoying performer who nails the part as a whole, making for an enjoyable flim-flam man in the nightclub and absolutely murdering a sequence in which her non-thespian character’s natural charisma unexpectedly blossoms in the pressure cooker of a screen test. But there’s more to come, much more: a dalliance betwen her and Korben, a potentially sexual involvement between the latter and Kate, a rising tide of anti-Semitism pointing towards the coming war, etc. Zlotowski’s dialogue is often actively bad, clunkily articulating themes (“I want to act to live”) and subtext. The ultimate effect is exhaustion.

Adam Leon’s Tramps logically proceeds from his debut, 2014’s innocuous Gimme the Loot, being another pairing of a boy and a girl tramping their way through NYC and surrounding areas. This time the two — Polish prole/aspiring chef Danny (Callum Turner), vaguely arty Ellie (Grace Van Patten) — are strangers rather than old friends, drawn together by a vaguely detailed criminal conspiracy to deliver a standard Macguffin suitcase. The details aren’t the point, just the pretext — Tramps feels like kids playing dress-up crime, but not in a good, charming way, just one that can’t be bothered to do the research groundwork.

By standard narrative film logic, a man and woman can only occupy the same proximate space for so long before they become an Item; the only surprise in Tramps is how fast it happens. Danny and Ellie have to go out of the city to chase down the suitcase. Silent on the train, upon exiting they walk in long shot along the platform towards the camera, and before they’re halfway along they go from no talking to sniffing each other out re: significant others, probing each other like a longtime couple on the verge of a fight. The relationship proceeds on over-brisk schedule: they grow closer, there’s a twist that causes a temporary split, and then a heartfelt reconciliation. The lack of surprises isn’t a problem per se, but the dialogue is flat throughout and the incidents strictly by the numbers: there is also a sequence of the two riding bicycles while crazy in young love.

There’s a lot of abrupt zooms and other signifiers (the talented Ashley Connor is the DP) of aiming for some loose, on-the-street ’70s energy, but no matter how conspicuously eclectic the soundtrack gets, no amount of funk horns or banjo-picking balladry is going to lend this any real energy. What Tramps has in common with Gimme the Loot is real estate envy: the latter’s best scenes involved a (black) drug dealer visiting a rich (white) girl’s apartment, almost making out with her on his first delivery only to be mocked when he returns to finish the job and encounters her no longer bored and maintaining status among friends. The message is clear: the economic/class gap between the wealthy and everyone else in NYC is basically unbridgeable, meaning everyone who’s not loaded is now, by relative default, part of the service economy. Tramps has a reprise of this scene, and a thirst for Briarcliff houses: “The whole point of being out here is so they don’t have to worry about people like us,” observes Ellie. That’s true, and one of the very few times the film springs to non-generic life.